Interview: Kevin Carillo

To listen to the interview, scroll to the Player at the bottom of the page.

"As a Tico Nosareño and surfer, I love this place. It’s so good. This place is magical. A lot of things that you can learn. The waves, surfing is so good. Just like taking off like just get up on the wave, it’s gonna feel like something magical inside of you, like butterflies on your belly, something like that, it’s gonna like, feels like, this is like heaven."

~Kevin Pipin Carillo

Show Notes

The ATV tour service, Pippin Rentals, Kevin and his family operate in Nosara.

The surf school where Kevin teaches, Safari Surf.

National Geographic Article on Blue Zones (where people routinely live longer than average)

Peer reviewed article about how research into Blue Zones led to this conclucion: “putting the responsibility of curating a healthy environment on an individual does not work, but through policy and environmental changes the Blue Zones Project Communities have been able to increase life expectancy, reduce obesity and make the healthy choice the easy choice for millions of Americans.”

Who to contact to book tortilla lesson when you’re visiting Nosara (Conocer)

Wikipedia Entry on Catalan

Interview Transcript

Intro Part 1

My name is Maia Dery.

The Waves to Wisdom interviews are the result of an exploration into a world I discovered when I learned to surf at mid-life.

Some of these conversations aren’t necessarily with people who we would instantly recognize as leaders but they are all leading us in a direction I instinctively followed and have benefitted tremendously in the process. Some of them don’t have huge audiences, but they are living very large lives.

To me, these people all seem to have wisdom practices centered on their relationship to the more-than-human world, to what we usually think of as “nature.”

Surfing proved first revelatory, then revolutionary in my life. I thought I was creative, thought I knew and loved water, thought I took care of my body. But when I entered the world of surfing and waves, when I started to ritualistically return to a literal edge, I realized my vision for my life had been hampered by some artificial barriers.

Slowly, with each wave and wipeout, those barriers in my brain, heart, and body began to dissolve.

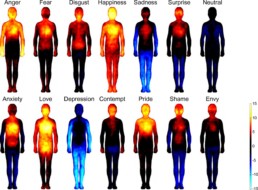

I began to wonder, what if we all had a nature based practice that cracked us open? Made us more creative? Allowed us to reliably let go with the abandon of play? Of unbridled joy? What if we all practiced vulnerability, risk and failure on a daily basis and they were fun? Wouldn’t it make our lives better? Wouldn’t it lead us to the places it feels like, in this moment of planetary peril, we need to go?

Whether you find full bodied and big hearted connection through waves or walking or digging in the dirt, I hope you find these conversations useful in your own journey of re-inhabiting your life with renewed joy, deep engagement, and increasing wisdom.

Kevin: As a Tico Nosareño and surfer, I love this place. It’s so good. This place is magical. A lot of things that you can learn. The waves, surfing is so good. Just like taking off like just get up on the wave, it’s gonna feel like something magical inside of you, like butterflies on your belly, something like that, it’s gonna like, feels like, this is like heaven.

Intro Part 2

Maia: Kevin Carillo is a young surf instructor from Nosara, Costa Rica, a small jungle community dominated by American and European expatriate surfers and yogis. Over the last five years This place and the people who grew up there have,, become a strong current in my own heart, pulling me back over and over. Each time I return I learn more about the Pura Vida culture of the locals and, in turn my own culture’s predispositions leading us to define ourselves by accomplishment over relationship or work over love. The interview is with Kevin, a human but we recorded this conversation near the end of Nosara’s dry season, just a couple of days after the first rain. Along with that rain comes a gathering wave of new life, including, as you’ll hear loud and clear, crickets. It seemed fitting that, in a place where the waves, trees, hills, and wildlife are abundant, the jungle would make it’s voice heard.

Kevin’s ability to describe, in his second language, no less, the ways that the lessons he’s learned from the waves have helped him overcome stress and temptation, sort out his priorities, and grow up to be a strong, happy teacher, partner, and expectant father reminded me that wisdom is not always a result of age. Sometimes a disciplined play practice in the more than human world, something like surfing, can help us figure our lives out in what seems to me to be very brief time. Welcome to Waves to Wisdom.

Kevin: Hello Maia

Maia: Hello Kevin, will you, let’s start by telling everybody your name, your age and how long you been surfing.

Kevin: My name is Kevin Carillo. I am from Nosara, a local surfer here and I am 24 years old and I’ve been surfing for 10 years.

Maia: and did you learn from someone in your family or friends? (0:46)

Kevin: I had a friend, a classmate and he surfed, said, “Hey, you should surf!” He’s from Garza. His name is Steven. And I start surfing but just by myself. I tried by myself.

Maia: And and was it reasonably easy to learn by yourself?

Kevin: It was hard. I just remembered I just wipeout a lot on the sand.

Maia:[Laugh] But you must’ve liked it enough to continue despite the frustration.

Kevin: I know because that was the thing that you as I kid like something that you want to learn, it’s like okay I need to get this I need to get it. I need to try, doesn’t matter how hard it is, I need to get it.

Maia: And clearly you got it.

Kevin: And I got it

Maia: You got it— okay how long did it take you?

Kevin: I remember like took me like two weeks just to get up on that big board.

Maia: I’m pretty sure it took me about two years so— not too bad but I was 40 not 14 when I started. Excellent and then how long did it take you to fall in love with it?

Kevin: Since the first day.

Maia The first day even though it was frustrating [yes} you loved it right away?

Kevin: Yes, since the first day. [OK] Because I kept on going [yes] kept on going.

Maia: and and you already had a relationship with the ocean? You knew how to swim?

Kevin: I know how to swim. [okay] Yeah I knew how to swim cause here in Nosara we learn how to swim since we are like four years old. Like, little little little kids. Cause we are being on the rivers, jumping from the bridge, getting on, we call that “possas”– when the river has a little deep water, maybe a tree next to the river and we just go on the tree and jump.

Maia: And the kids love it? [yes] okay fantastic okay so you work for school, a surf school. And who do you mostly teach lessons to here in Nosara?

Kevin: Mostly beginners. A lot of beginners— just first day, trying in the whitewater and it’s like, it’s really good. I love it.

Maia: What do you love about it?

Kevin: I love the smile on their face yeah. Cause when they got that wave, when they get up, cause first they tell you, like, “I’m not good at this. I never tried this, and I’m pretty sure I’m going to not do this, since it’s the first day. “ So they have a perspective like maybe I get it but really long. You know? And when they get it since the first wave, cause sometimes they get up on the first wave, its’ like, “I got up!”

Maia: And what what sort of people, like what ages and where they from mostly?

Kevin: Mostly from the United States, there’s a lot of people from United States. There’s like an age that mostly come here to surf that is like 30 to 50. There is like a lot of people that age that want to surf.

Maia: I’ve noticed that too and I have noticed that this is a place where a lot of single women travelers seem to come to learn to surf and even older women [yes] lots of women older than I am if you can imagine that.

Kevin: Yes, it’s so good. I love that.

Maia: It’s really good, isn’t it? What do you love about it?

Kevin : That you can see that there’s no time, there’s no age but you can practice a sport, even though it’s hard, you could see like 10 feet waves and you still see old lady surfing. Or it’s small and she’s enjoying the wave you can see it doesn’t matter the age.

Maia: It doesn’t matter does it? And this beach that you teach on is a particularly good beach to learn, isn’t it?

Kevin: Yes, it’s because it’s a beach break [yes] no rocks and the wave is like small, soft, really good to learn.

Maia: So fun! The long rides here are just so fun. Do you think the fact that you were surfing as as a young boy, as a young man, did that change the way your life went in high school and afterwards?

Kevin: Of course, yes.

Maia: And it obviously, since you’re now a professional in the surf industry, it changed in that way. Did it change it any other ways, maybe earlier or affect how you made decisions or what decisions you made?

Kevin: I remember in college, like, high school I was in the last grade, just graduating to go to the University and here in Costa Rica you gotta do a final test, like five tests, like math, biology, science, English and it’s like a hard test because you don’t know what you see on the test it’s just like go and do the tests and I already surfed on the time and I remember I was so stressed out, like studying a lot. And I was like, no, I need to relax, I need to go surf, I need to be the water, take my time, see some waves, see like how it’s going to make me calm down and it helped me to win the test and I got the test and I got graduated.

Maia: It was fine. So you felt stress which you were pretty sure was gonna impede your performance, you weren’t going to do as well as you could have if you weren’t stressed. You knew by that point— you’d been surfing for four years then? Three or four years [yes, yes] and and you knew that if you went surfing that you would be able to handle that test without stress. [yeah] and so you already had that coping mechanism?

Kevin: Yes

Maia: That that sounds like wisdom right there. Good what. what other ways as a young person did surfing affect your life?

Kevin: Um Well taking decisions to be more responsible. So if you go to surf and if you don’t take the right wave you gonna wipe out, you gonna fall off.

Maia: So you learned when you were surfing that you didn’t go for every wave? [no] You had to pick the right wave for you [yes] and that translated to your life on shore. You metaphorically saw that there’s a path in life that, if you take it [yes] you’re gonna wipe out.

Kevin: Yes, you’re gonna wipe out.

Maia: No bueno. [laugh]

Kevin: No bueno. And yeah as a kid as a kid it is hard because those are things that, for a kid is really hard to take you know and like the surfing industry is like many things that you’re gonna see like drugs or alcohol, those things. So you gotta take it easy. Do the right things, go study, be responsible even though you surf still like you have other the things to do.

So, bad things you gonna see, not good friends not good friends. Friends that are going to tell you to do something, supposed to be friends right? And they going to say okay this is the surfing life. The surfing life is like, go surf, get out of the water, get changed and then go party, drink, do drugs, and maybe get a girl and then go back and wake up the next day just feeling empty and do it again. But that’s not not surfing.

Maia: That’s not surfing?

Kevin: That’s not surfing.

Maia: No. It really is for, for people who have not been here to Nosara the surf instructors are sort of alphas.Do you know that phrase? [yes] they’re in some ways they’re the people on the beach with the most status—the surf instructors. You’re all very good surfers most of you are young [yes] most of you are strong and handsome or beautiful and and there are endless waves of incoming tourists many of whom are beautiful and young and in search of a good time for the week or two that they are here.

I can imagine how for a teenage boy, or a very young man, that situation would be full of temptations—all of these people coming in with money and a desire to party. [yes] and and somehow you’ve managed to navigate all of that [yes] without, as you say, going a bad way. And you think that surfing helped you with that?

Kevin: Surfing helps, yes. It’s like if you feel like those things are going together, those bad things like what you say, like girls coming here to get party, alcohol, drugs, friends. But surfing helps like okay, relax calm down. This is not what you need to do. You need to clear your mind. Surfing like helps like clear your a lot.

Maia: So not just if you have a stressful situation like a specific test. But it sounds like if you have a larger stressful situation like figuring out how to live a life in a situation where that the bad path is easily accessible. Surfing it sounds like helped you navigate that.

Kevin: Yeah cause like you have goals right here. Surfing is like you set up goals first you’re like okay “I’m gonna get up on the board, I’m gonna turn to the side, I’m gonna cutback, I’m gonna paddle to the outside.” You’re thinking about your goals. You go little by little, doing something. It is like life, okay you need to do this thing first, it’s not like like, I’m gonna get a board, paddle out, it is not how you do it, you go little by little, take your time, set up like the right things that you need to first, and and start getting to do with those goals right? And then you’re gonna be surfing really good or you’re gonna be having a good life.

Maia: And speaking of good life, will you tell everybody your very exciting news?

Kevin: Well I’m,I’m having a baby. I’m so excited for that! Having a little boy. His name is Andreu. And I hope and I hope he gets like a good surfer. I hope he surfs. Yeah and I’m so happy to surf with him. And teach him how to surf and teach him how to live the life really good. Enjoy the life.

Maia: And when you said enjoy the life what is what is a good life to you? What is, what do you notice is a good life?

Kevin: Wake up smiling. Smiling because you are, you have a good partner on your side, a good person, with good karma, good soul and pull you up, right? With happiness. That’s a good life and go to the water, go surf at least like one hour, go surf, clear your mind, feel the sun on your face burning, especially this month, March. And enjoy the water and then like maybe go to a job, meet people, have friends, that’s a good life.

Maia That’s a good life.

Kevin: Learn some culture and eat a lot.

Maia: Eat a lot! That’s a good life!

Kevin: Yes.

Maia: There’s a concept or an expression or a way of being here that you all call Pura Vida. Could you tell anybody is listening what is Pura Vida from your perspective?

Kevin: Pura Vida is like living life in a good way. You need to live the life healthy, happy, be friendly with others, that’s Pure Vida, even though you don’t know that person, giving a smile because you don’t know what he is living. That’s Pure Vida. Like be interested in his happiness. Like like, hey hello how are you? Have a good day. That make you be a Pure Vida person and that’s the Pure Vida life here. Like we live healthy, we live happy, we love our place, we love our culture, and we take care of these little piece of land. And love the people that are here. And we help help a lot, like if if you go on the road and someone is stuck with the car that is not working broken, you stop and help him.

Maia: That’s Pure Vida.

Kevin: That’s Pure Vida.

Maia: Just so that people understand it you see a lot of people coming here from other places that don’t live in a Pure Vida way [yes] they don’t. What does that look like? What is Pura Vida the opposite of?

Kevin: People who are too stressed out, people who wants to hurt other people, they just come here, destroy this piece of land and destroy the happiness that other people are living. He’s like too stressed out, needs to relax calm down breathe.

Maia: Yeah. So you were young man and you it sounds like you you had a moment where you were probably tempted to do these bad things, to live this party lifestyle. In that moment how do you think you were able to make a good decision for yourself?

Kevin: Cause I start when I was young, in high school, so there are like friends and there are like a lot of temptation like, let’s go out, party. And I did, I went to parties and I get crazy and it was not good, I was not feeling good. I was feeling empty every single day. And like you start thinking that’s the way you need to live because everybody does that. And you think that you are doing the right things, that you’re living a good way because you have money and you are paying for going out, and you’re paying for everything that you need, but it’s not, it’s not healthy but then I realize that I need to live in a different way.

Maybe from my family? I see my family like living really good, I have a good family, especially my brother. So it’s like, graduated, work, get your house because you need a house to live and then you can get the rest. Because my mom said, this is what my mom told me all the time since I was young, like, “Get a job— study, get a job, get a house and then you can do whatever you want.”

Maia: it’s very interesting to hear that that your mother and surfing reinforced each other. Your mother said, “Take these steps in this order.” and you learn from surfing you don’t just go right out in the big waves, you have to take these steps in this order and then you don’t get hurt and that’s, that’s pretty wonderful.

So you went to college and what did you study?

Kevin: I studied to be so first I went to public university [okay] and I studied just to know English, just just to know. For two years was like from Monday to Friday. And it was like from 8 in the morning to 9 p.m. A long time just studying. Not too much for surfing, just on the weekends. So I need to get up really early on Friday or Saturday come to the beach, surf, and then late Sunday go back to study again. And then I finished that. I got a job to be a surf instructor. And the company that I’m working right now they help me a lot to get money and then pay for another career. And I studied to be a English teacher for elementary school and it’s so good.

Maia: It’s so good. So you got your degree in elementary English education? [Yes] And why is it so good? Tell me what’s so good about that?

Kevin: Because you are because your education keep your teaching kids you are teaching things that you know so you better do it good and feel good for it because that’s gonna be the future of this world.

Maia: Okay so so your little boy, Andreu, he will speak English and Spanish?

Kevin: He will speak English, Spanish, Catalan, from Barcelona, and Italian.

Maia: And Italian— so he will he will have four languages? [I know] My goodness.

Kevin: He’s gonna be a good guy, he’s gonna be a int… guy, he’s going to be really interesting.

Maia: He’s gonna be really interesting.

Kevin: Yeah all the ladies gonna be looking at him.

Maia: Yes he is going to be very attractive to whoever he wants to attract I am sure, yes so good! Okay, good so you have because you are a professional surf instructor, [yes] and by choice you could be a teacher, obviously, you are qualified to be a teacher of English but you are the teacher of surfing instead. You’ve watched a lot of people go from not being able to surf at all to be able to surf a little bit or maybe even a lot. Because one of the things I’ve noticed about your clientele your customers is that they come back. They’re so happy after coming here for one week and working with one of you, you are all such wonderful, warmhearted pure vida instructors. People, you know, by the last day sometimes they’re in tears. They don’t want to go home. [No] They’re in love with you and this place and the waves. They come back and they get better! [Yes] Even if they don’t live near waves themselves.

What have you noticed that learning to surf either through your own life or watching so many people of all ages learn to do it— what have you noticed that that does for people?

Kevin: So when they come here, some of them, well like mainly, maybe all of them? They come here, a new place, they don’t know anything about here. They just know okay, I need a place to learn how to surf and a place that help mostly for kids, right? And they come here for some surfing and they get this life here, the way that we treat them, cause we like to treat them really good. We try to give them the pura vida that we have. So they come here and it’s not only like surfing.

Maia: Okay, so in what ways do you think that these people coming to surf, how can you see it change them as they get into the water, begin this process of working with the ocean, making mistakes?

Kevin: Yeah they they come here and they get related to the ocean and they start feeling like okay it’s a good sport to try, it’s not hard, it’s easy it’s really easy, surfing, is easy if you set your goals, “Okay I’m gonna do this.” and then just do the right things, like getting up, back foot, front foot and surf the wave and they start learning little by little new things. They get interested in the surfing life. And they want to learn more. The same like me. Like, you start learning new things every single day and then not only surfing, maybe like, living here in Nosara, like living with us, with instructors, We treat them, we are like a family here. We host them like brothers, like this is my younger brother or my old brother, my sister, or sometimes like there come old ladies and we call them “Okay, Mama!” Cause you are like my mom. We are gonna treat you like you are my mom and we are happy to have you and be like a family and surf and eat and laugh.

Maia: I can attest to that because, in a lot of places that are dominated by surf culture what that winds up looking like is that those places and that culture are dominated by young men who are good at surfing, that sometimes happens, and there sometimes isn’t a place for people like me, you know a middle-aged women and that is not the case here is it is so beautiful it is like I’m your mother or your aunt or somebody su tía, su mamá, somebody important to you all. And really the pure vida is palpable, it’s a wonderful welcoming vibe all the time no matter who you are or how good or bad, technically speaking, you are at surfing. [Yes] What did surfing teach you is there anything that we haven’t talked about that surfing taught you in terms of a life lesson.

Kevin: Um, yeah, like surfing, like sometimes if you feel like you’re gonna take bad decisions surfing might help you a lot, like clear your mind, feel the ocean, feel the wind that’s going to make you calm down and think clear, think what’s better for you (3:28). And if you just do whatever seems faster, something seems faster and you just want to take it maybe it’s not the right thing. So for living, it’s like taking good decisions taking good decisions like the same wave like if you see a wave and it looks good, sometime you see a wave and it looks good it looks like a perfect wave but it’s not, it’s too short. Let’s wait for the second one or the third one. That’s the one that you need, it’s not the first one, you don’t need that one, even though it looks good but it’s not the one that will fill you up so for living you’re gonna see you like bad decisions coming up like did you take this and maybe it’s not right for you.

So that’s what happened to me like okay I need to study, I need to get a job, and then once you get that you need to get the second step and then you need a good partner with you, you need a good partner that help you that make you like grow up right? That don’t make you get stuck right there. That’s really important too. So it’s not a girl that you’re gonna find at the party and then just go out just one night And that’s the girl, no.You need to know the lady, to know the girl, surf together, yeah? surf together, know pretty well and then you do the decision. So it helped me a lot.

Maia: And tell us something about your partner

Kevin: She’s, she’s a good surfer. But I love surfing with her. I love that. And we start talking, we started exploring all the area right here in Nosara cause I’m still, I live here, but still there’s many things that you can see, like the first time. And we did some ATV tours, we went to some waterfalls and we did some trips to surf and we started talking (6:45) to know each other and then I realize that she’s a nice person cause so inspire, like, something really good that you can see through her eyes that she’s she’s so nice and, yeah, I love her a lot.

Maia: She is beautiful in every way a person can be.

Maia: and I understand your father also has an intimate relationship with the ocean.

Kevin: He’s a fisherman. He loves fishing and he taught me how to understand the ocean lot cause he knows really well the ocean because he knows really good the moon. Yeah. I don’t know but he understand the moon really, really good and if you asked I can ask him right now like what moon do we have right now he will tell you right away and he will say okay this is, the moon is right here, is like this so the tide is low so when you have this moon, this tide, the we can catch fish.

Maia: So your family, I’m lucky and I am lucky enough to have been to your house, and your family owns a beautiful piece of land I don’t know how much but a lot of land you as far as you can see really from your house there are Carillos. And how far back does your family go in Nosara?

Kevin: It was like a long time ago my, my mom, well, my grandpa and my grandma they were from Nicoya, they were living in Nicoya and then my grandpa sold that land and moved to here Guiones or Nosara and then he got that land for like 25 colones.

Maia: 25 Colones?

Kevin: Which is just like

Maia: 50 cents?

Kevin: Something like that.

Maia: And he got this land and start living here with my mom my aunts all my family open, and now he’s old, now he’s really old, he’s 97 [my goodness] Yeah, he’s 97 and we still have this land and I’m living one piece of that cause my mom got gave me and it’s a nice place because it’s all family right there.

Maia: So beautiful! And you live right next door to your 97-year-old grandfather don’t you?

Kevin: I live next to him and I see him every single day [every single day] and he is still walking by

he’s walking by himself he wave at me when he saw me and we made jokes, he loves jokes.

Maia: Well, it’s interesting because he grew up in Nicoya and this whole area around Nicoya is a blue zone [it’s a blue zone]. Zona azul, sí? What is a blue zone?

Kevin: It’s where the people live because longer we have people here who live a long, long, long time. I know people who get more than hundred years.

Maia: Wow [because he’s happy] he’s happy do you, I mean you’re not a scientist and I’m not a scientist and I and I don’t know that there have been scientific studies trying to figure out why people in Blue Zones live so long but you have any opinions about why?

Kevin: I hear what I’ve been realizing that the corn [the corn?]. The corn— so the corn so what happened here I know like for my family you say when you go to eat you always have to get a tortilla on your plate.

We don’t we don’t get Coca-Cola, we don’t get Fanta, that’s what they were drinking before. We get chicheme. Chicheme is a drink based on corn based on corn, is a corn that is purple and the it could something different to get the drink all the grandma and grandpa’s how do they know I double with the were drinking and eating really healthy things.

Maia: Interesting

Kevin: And we grow up fruits right here, fruits vegetables [so many] a lot of sandias

Maia: Sandias! Watermelons…

Kevin: The watermelons are so good.

Maia: People just throw the watermelon meat right in the blender and blend it up and drink it. It’s delicious!

Kevin: That’s why we get longer.

Maia: That’s why you live longer. I suspect pure vida has something to do with it too, the just openhearted, accepting, loving, generous attitude people have towards one another, not everyone but, but culturally.

Kevin: Yeah I told you like, being healthy if you are healthy people if you are healthy, person if you’re eating good and living this life, you gonna be a nice person, you’re gonna be smiling the whole time, you won’t be angry, you’re not gonna be mad at mad at anything

Maia: From my perspective one of the problems I see with this place is that a lot of Americans and Europeans come to Guiones and many of them miss out on pura vida because they only talk to other Americans or Europeans. And in groups that I have have brought your students and and also retreat groups it’s inevitably the one thing that they remember most, now they have a great time I mean there’s there’s world-class yoga here in these beautiful yoga studios, the surfing is so exciting, the beach is spectacular it looks like the cover of a fancy magazine every single day, it’s so beautiful. But every single trip where I’ve brought people the thing that they remember most is when we go to the home of a local and they learn how to make tortillas the local way. [yes] That’s always the thing that moves them the most.

Kevin: Here like everybody know how to make a tortilla.

Maia: Yes and and just the authentic experience of interacting with the people and so many… it’s interesting I see a lot of Americans come here and they they keep separate from the people and maybe talk to a Tico surf instructor but they they don’t get out of this little village and they don’t get out to some of the places that you take them, Pippin Rentals, and it’s such a shame because when they do get out, as you say, it fills you up so much more the experience it when you really, even just for half a day, when you really feel the culture and in the way of living here. It makes the whole trip, even if it’s only a week long, it makes it so much more meaningful and the love that you feel for this place is so much deeper because it’s not just about what can I get how good a time can I have here it becomes about this exchange were you’re talking to people and they’re talking to you and and it isn’t so unequal. Because one of the problems here and in many places in the developing world where wealthy Americans come to vacation is inequality. There are people who make very little money and then Americans building two million-dollar homes and the prices get very expensive for food and housing and and these are challenges, the gentrification. These are challenges that the that this place faces but those challenges seem less insurmountable when you watch the wealthy visitors interact with the locals as humans, human to human it really, in my experience, at least, it makes a big difference.

Kevin: Yeah that’s really important interactions with the local person right here is really good just like we do surf lessons is not only like the whole time just talking about surfing they talk to you about like how you living, what do you do, what else do you do besides surfing, and you get a conversation with them so people who come here they, they love chatting, like they love talking.

It’s gonna be fine. It’s gonna be really good chatting with the local person so know about the life here. How’s the life in Nosara? How’s the pure vida? So like they gonna show like yeah we eat healthy we eat tortilla, we made it like this. How to make chichi my or how to make tamarindo. so many things that you can learn from a local person. So many things and they… you gonna feel so good to learn those things from a new culture, from a new place it’s not only likes to surf or somebody just yoga, yoga, yoga with a person that you, that doesn’t even know the place many people come here, start living here and they are from United States or they’re from Europe and they are living here for ten years maybe, they are living here for 10 years and they think they are becoming local person, local people so that’s the one that like sometimes I like not getting into the pure vida life. You know?

Maia: Absolutely

Kevin: And yeah this place is getting bigger. Many people are investing this place and the prices are going like in the clouds. It’s really, really high prices, really big prices and we as a Costa Rican people, as a local people, we pay the same, we pay the same but we don’t get paid when we get the job we don’t get paid at the same to afford those prices.

Maia: It’s, three dollars an hour is very standard isn’t it?

Kevin: Yes. So yeah that’s what happen it’s getting really big this place.

Maia: Ok, Would you say that all Costa Ricans or most Costa Ricans live la pura vida?

Kevin: No, not really. So, Costa Rica’s not that big but there’s many places the capital city, the center of Costa Rica we cal the Central Valley, that part, there’s more violence right there, cause like there’s more buildings, there’s more cars, more people the life right there is like a little more faster. Maybe like, like a big city in the United States. Not that big but for us seems to be like really fast.

Maia: And are people in the in the big cities here stressed-out?

Kevin: Yes, stressed out because of traffic, because they live in the way that is just like, wake up, go on the road, on the street, be like an hour, hour and a half in the traffic, go to work, stress out with their boss, and then go back to the street again. Then go home at night, eat something fast and wake and go to sleep and wake up again in the same way, every single day. And they have long period of working maybe and then maybe at the end they have a little vacations, but it’s still like stress out [and it’s not] maybe they don’t surf.

Maia: And maybe they don’t surf, which makes a big difference [yes]. Because you, it would be easy for somebody listening to this to think that you don’t you that you don’t work like that. But in fact, especially during the high season, during the busy season here, I’ve watched you now for weeks in a row start with lessons at 7:30 in the morning

Kevin: Or start sometimes like 6!

Maia: Sometimes at 6 and teach right until the sun goes down you at at 5:45 at night and it’s hard physical labor, pushing people into waves.

Kevin: So you must be in shape, you must have like muscles and be in shape, and be eating healthy and drink a lot of water, because like, we been working a lot, the whole day in the water, I don’t even change my clothes, I just be wet the whole time. Just start us the lesson at 7, do hour and 1/2, go back, get the next one, just drink a little water, sometime a little time for a little breakfast, then get to lunch, get in the water again, until 6. until the sunset . And it’s, good is, a good life. And now I have a little more time off and I’m spending that time surfing which is I am still getting tired but my mind is like out of the stress I’m not stressful because I’m surfing. All my stress is on the water, it’s gone, the ocean took that stress and I feel so good. Mostly when I was surfing with Maia

Maia: We have had some really fun times, haven’t we? [yes] Yes, yes. And you’re, you’re so generous. Sometimes the waves here get quite big and and occasionally they’re, they’re fast. It’s a pretty slow break in general but occasionally they’re fast and you’re always very good about telling me whether or not you think I’m ready to take off on a particularly challenging wave. It’s nice to have that reassurance.

Yeah I noticed, I mean it really is remarkable, because your job is very intense, I mean people, it’s the ocean, things can happen out there. Just the other day we were surfing in the morning and you paddled up and it was so cute you said, “Are you gonna stay out here for a while?” and I said “Well, yes.” and and you said, “Well, there’s a 4 or 5 foot shark over there.” [laugh] [yes] It was like oh, okay well maybe I’m not gonna stay out here for awhile. But even at the end of the day after five lessons or six lessons, you’re so good to people and so patient with them, and take such good care.

You, just this morning, the waves were so good and you told me, I asked if you got any of them when they were good and you said no I couldn’t take off because I was with a mother and children who…

Kevin: Two little girls [with two little girls] like 14 years old.

Maia: Okay and and they, you couldn’t leave them to take a wave, that you needed to stay with them.

Kevin: I need to stay with them and there were good wave, so good, [so good] I still remember that wave coming, there were like five of them, and I was like. “Okay no I need to let this wave go.” [yes] because those waves were not good for them because it was a little steep [yes] and I love steep waves [yes] because I can make some tricks [yes- laugh] in they were no good for them so that I told them this is not good for you we’re gonna wait for another one who would fit you better.

Maia: Which is just wonderful and, and I, there are many surf schools here, there must be almost 20 surf schools in this tiny village now,

Kevin: I think more than that.

Maia: Even more than 20… and I have watched many instructors from other surf schools leave [yes] clients so that they could take a wave and it’s one of the reasons that I have formed such a close relationship with you all over these year’s is that you you really do put your clients’, not just safety but, but comfort first.

Kevin: Yes. Because it’s a place, it’s a new world outside, like on the break, that part is like a new world. There are many things, there’s gonna be people, there’s gonna be waves ,there’s gonna be, sometimes, animals, so it’s a new world. So and they’re not gonna be used to that.

Maia: Is there anything else about your life as a surfer, your relationship with the ocean, you as a as a Nosareño, is there anything that you would like to say to anybody listening?

Kevin: As a Tico Nosareño and surfer, I love this place. It’s so good. This place is magical. A lot of things that you can learn. The waves, surfing is so good. Just like taking off like just get up on the wave, it’s gonna feel like something magical inside of you, like butterflies on your belly, something like that, it’s gonna like, feels like, this is like heaven— how the nature made that and you can use that power of nature and you can surf that. Because it’s not like you make it right? It’s just like okay, it’s coming by themself because God made that wave because the nature of the current is a wave, the wind made this kinda wave perfect, just for you. And just surf it, get it, and it’s like the life. Like this is your life, enjoy it, on the way they’re going to be bad things just move it around, skip it, like when you’re surfing you skip some people and move to the side, go to the other side, don’t look what you don’t need to look and chosen joy.

Maia: It’s good good life advice, just enjoy it.

Kevin: Just enjoy it. Just enjoy what you having in the moment. Don’t think about like way too far. Just think about right now, the present. And live the present right now.

Maia: It is something that that people here seem to be very good at is enjoying the moment, taking time to be with their families. So many people just go out and watch the sunset together, play soccer with their kids on the beach. They don’t work, you now, all the time, if they don’t absolutely have to and it’s it’s a beautiful thing to see. And there certainly are, they’re are a lot of of owners of businesses as as we’ve discussed who sometimes demand longer hours than is healthy for the employees but when people have a choice they really do seem to put love, to put being with their families and being with their friends, it’s a very high priority.

Well thank you so much Kevin [you’re welcome]. This has been just wonderful I feel like I learned a ton and I know everybody listening will too.

Kevin: I hope they learn a lot from this, and yeah you’re welcome.

Maia: I hope you enjoyed Kevin’s wonderful perspective on life, love, and waves. To set up a time for an exploratory conversation about coaching, a custom Waves to Wisdom retreat in Nosara or the US, or an inspiring, energizing event for your organization or group visit wavestowisdom.com.

Interview: Michael Coleman

To listen to the interview, scroll to the Player at the bottom of the page.

"... with ALS when you lose muscle that includes tongue and throat and so swallowing can be a challenge and aspiration, choking can be a danger. So he does aspirate and choke a little bit sometimes... he feels like he’s able to get through that because of skills he learned from surfing when you get pounded and knocked under and your rolling around having to hold your breath underwater and stay calm and you know find your way through it and find your way up."

~Ruth Coleman for Michael

Interview Transcript

Introductory note about this show: I know from soliciting feedback from subscribers that many of you all are reading the transcripts rather than listening to the recording. In this case, I hope you will listen to at least some of it. As I note in the interview, Waves to Wisdom is on a fundamental level, a multidisciplinary exploration of how we can deepen and enhance relationship. Listening to the exchange between Michael and Ruth’s voices is, to my heart and ear, more powerful than the content itself.

All of these interviews are edited (the initial conversations can extend over hours) and I do not, as a matter of course, ask interviewees how they feel about the edited conversation. Rather, I ask for their trust up front. But Michael was hesitant about whether he wanted his voice out in the world and I wanted to make doubly sure he was happy with the result. He didn’t love the sound of his voice but, as he astutely noted, who does?

Transcript

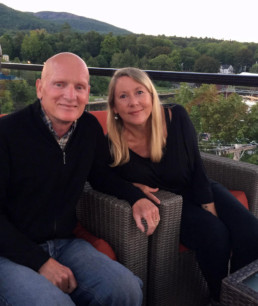

Intro: My name is Maia Dery. This episode is part of a series called the Waves to Wisdom Interviews. The project is a simple one. I seek out people I admire, surfers who seem to me to have ocean centered wisdom practices.

Usually, I ask them to share a surf session or two and, after we’ve ridden some waves together, talk to me about their oceanic habits, about surfing, work, meaning, anything that comes up. All of the episodes so far have spoken to the benefits and beauty of a long, intimate relationship between two bodies, the surfer and the ocean. This one’s a little different. Michael Coleman has been a surfer for more than 40 years. Just 8 years ago, he was diagnosed with a debilitating illness meant he had to face letting go of riding waves and, eventually, getting in the water at all.

But the waves continue to infuse his life with wisdom, both practical and profound. He and his wife Ruth Coleman were generous enough to share some of Michael’s story and, although we couldn’t be in the ocean in the same place and time, both Colemans left me so deeply inspired I’ve carried them with me into almost every wave I’ve ridden since our time together.

Oceanic wisdom comes in many forms. In her book, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit wrote about the way hermit crabs look for shells that weren’t really made for them and then mold their soft bodies to fit the shape of them. A set of internal claws clings to the shell while the external claws do their work in the world. She goes on,

“Many love stories are like the shells of hermit crabs, though others are more like chambered nautiluses, whose architecture grows with the inhabitant and whose abandoned smaller chambers are lighter than water and let them float in the sea.”

My time with the Colemans told two love stories, their own and Michael’s long passion for living life to the utmost. Welcome to Waves to Wisdom.

Maia: If you are comfortable with it would you tell us your name, your age, and how long you’ve been surfing?

Michael: My name is Michael Coleman I’m 60 years old I’ve been surfing since 1975

Maia: Fantastic — and where did you first learn to surf?

Michael then Ruth:

Ogonquit Beach [Ogonquit Beach] Maine [Maine] okay and so you, you were a young man at that point?

Michael: I think my junior or senior year in high school.

Ruth: His junior or senior year in high school as a summer job he was a lifeguard. So I think you were probably 17? 16, 17, when he first started.

Maia: Okay. And this, as I was just telling the two of you all, this is an unusual interview because usually there two of us. Do you want to tell us why there are three of us?

Michael: Well, I can’t speak very well because I have ALS.

Ruth: So he said as you can probably hear I can’t speak very well because I have ALS so Ruthy is speaking for me, or can understand me pretty well. So I’m Ruth, Michael’s wife, we’ve known each other since before he was 17 [laugh] [Wow, I didn’t know that part of the story] so you can do the math! and that that’s why I’m good at understanding him.

Maia: Probably in lots of ways. Not just this one…

Ruth: Yeah.

Maia: And so, I believe I recall you saying you surfed until about five years ago? [yes] Yes, until about five years ago? OK, and did, I mean starting to surf at 16 or 17 you know, one is not fully formed, certainly, at that age, do you feel like surfing impacted the adult that you grew into?

Michael: Yes.

I think that surfing was the impetus to travel.

Ruth: It was the, gave him the impetus to travel. Made him want to travel, to go other places for surfing…. Learning about other cultures. So surfing gave you the desire to travel and then traveling gave you the desire to learn more about other cultures. [mmm hm] (5:04) You like to go to places where surfing is available but it’s not like the only thing the place is known for. It doesn’t overwhelm the location, what was already there. Yeah.

Maia:

So we’re in your living room of your beautiful new house, this is your downsizing house in Rockport Maine. Rockport’s not known for surfing either.

Ruth: [Laugh] No

Maia: How did you wind up choosing Rockport?

Ruth: Michael took a motorcycle trip. Barry had given him um just some little ad for a piece of land or something that was randomly in Rockport. I had never really been here other than driving through. And Michael took a motorcycle ride and came up and looked at it and put some money down [Oh my goodness, really?] on the property and we were married then and we were thinking about building or buying a house but we hadn’t really been thinking about that and we were thinking about moving out of Southern Maine because it was just going through a lot of changes at that time that explosion of condos and we just felt, I dunno, it didn’t feel right to us. But so yeah that was kind of random so he put a down payment on that land and continued paying for it for about a year and then the year after we got married we, I applied for jobs and we came up here and built our first house.

Maia: Wow. So you had to travel to surf? Did you get to do that often?

Michael: … It felt like it

Ruth: It felt like it. At that time you were working for yourself so he had flexibility.

Maia: And how often do you think you went down to surf?

Michael: …

Ruth: Whenever there was… when the waves were good… that’s the whole thing about the WeatherBand. That’s why we were always listening to the NOAA WeatherBand.

https://www.weather.gov/ama/nwr

Maia: Will you tell that story?

Ruth: LAUGH Just that, before the Internet, the way that you’d know about surf coming in Maine would be to listen to the NOAA weather and it would… surfers would be thinking ahead because certain conditions that NOAA would tell you about would indicate whether a swell and then waves were coming so Michael would just listen to that all the time. He’d fall asleep listening to it. [Michael muffled]

Ruth: Oh it was an automated voice.

Michael: On a loop.

Ruth: On a loop, yeah so it was annoying to everybody else but Michael loved listening to that LAUGH.

Maia: So did you go on some surf related adventures in your 20s before your kids came along?

Ruth: We started with international trips actually when we had kids.

Maia: For surfing?

Ruth: Yeah. Well, Dad, Michael… (laugh) all of our traveling were to locations where there were beaches LAUGH.

Maia: There were no family trips that didn’t involve at least some surf?

Michael: Why would there be?

Ruth: Why would there be? [LAUGH] Also, it just kind of made sense because living in Maine when you want to go away in the winter so where you want to go is someplace that’s warm that worked and in the summer we didn’t want to go away from Maine because that’s when Maine’s great.

Michael: Muffled

Ruth: Yeah, there were— we saw many other things as a result of surf trips, absolutely.

Maia: It was a force for good.

Ruth: Yeah, he would get up early and go surfing and there were still lots of family adventures.

Maia: One of the premises of this project is my untested theory that for some people who have this regular practice of surfing, of interacting with the ocean in this completely immersive, expansive way— that it helps them figure their life out. That it can make them better people or put them in touch with something bigger than themselves. Do you think, am I onto something? Is there any part of that that seems valid to you?

Michael: …Yes.

Ruth: Can I just say something while you’re thinking. It has struck me now in retrospect— I didn’t really get it at the time, but Michael used to talk about surfing as just being really pure and clean and he would feel really clean and his mind would feel really clean and it… In retrospect I realize it was like, before the trendiness of mindfulness and “ in the moment” that was exactly how you would describe things, is that you liked it because you were only focused on that because you have to you have to be paying attention to the, you know, the waves and the sets and what’s happening with the weather and all of that. And so, like I didn’t— that didn’t register to me at the time because it was before all that talk about mindfulness and being in the moment. But now in retrospect I look back and I think that’s how you always talked about it. That’s what you liked about it that you would be out there, you know, not necessarily alone because there’s other people surfing but you would be so intensely focused that sort of like wiped your mind clear.

Maia : Is there any other way in which it had practical or impractical benefits?

Ruth: Let me just make sure I got it so you’re saying in surfing is the last failure, you fall and you fall and you fall you fall again, and you have to get back up. Nobody is telling you you have to get back up but you just, you do it. And so the feeling of, then when you do get back up after all those falls and then you have success, that’s a really powerful feeling, that resilience.

Michael: muffled

Ruth: It changes you? [Michael muffled] It teaches you all those things like patience and to keep trying, getting up again. And those apply outside that’s what you said at the end there. That that resilience, that keep trying even when you’ve been knocked down that that… somehow you internalize that you feel like you applied it in other places.

Michael: … even today [even today] I think that in my current situation…

Ruth: In your current health situation. That resilience and ability to adapt.

Michael: Has helped me

Ruth: Has helped you with ALS

Maia: How long’s it been since you’ve been able to surf?

Ruth: 5 or 6 years and he was diagnosed with ALS more than 8 years ago. So you still surfed for a couple of years after you had ALS but you weren’t as greatly affected by it as you are now. As the progression continued it got harder.

Michael: I remember…

Ruth: He remembers a time in Costa Rica after he had ALS when his legs weren’t affected that badly but one of his arms in particular was and he felt like he was paddling in circles because one arm was weak one arm was strong. And how did that feel?

[LAUGH] He said at that time he was more focused on getting out to the waves before Carl, one of his buddies, so that bothered you? For that reason? Ok.

Maia: Are there any other ways, let’s think before ALS that you think this surfing might have had a positive influence on your life?

Ruth: Can I say one while you’re thinking? I think that you you just always had tremendous energy I think it was an outlet for your energy. I think I don’t know if you you feel that way about it but… and then looking back at thinking about how you said it that’s just what you like about it how it just kind of wiped your mind clean and I think it was that that you know that it takes a lot of physical effort to surf but it also had that meditative quality and that you— I just remember you being almost like driven to get there and then you would just feel like cleansed, or something after you, after you did it. And you always did a lot of sports remember? So and I think then when you had less opportunity for sports, team sports kind of in your life that surfing, fulfilled that need for that physical activity but it also was having that other mindfulness, meditative effect on you. When you could first see the waves

Michael: Oh my God, Oh my God, Oh my God…

Ruth: You couldn’t wait.

Michael: muffled…

Ruth: You could get out of your truck and be in the water in minutes.

Michael: muffled…

Ruth: Someone would say. “What do you think Mike?” Looking at the surf and he’d already be moving and saying “I’m not going to think about it I’m just getting in the water.”

Maia: So earlier you got out a copy of Surfer Magazine from 1990, was it? [uh hm] and there in the pages of Surfer Magazine is a picture of Michael Coleman on a huge, looks like about to be barreling left, what’s the story of that?

Michael: I will let Ruth tell it.

Ruth: I don’t really know the story just that you were out there and someone was taking pictures because it was pretty epic surf for Maine and that the picture that got into Surfer Magazine the caption that went with it was something like, “Mike Coleman biting it Maine style” because it looks like he’s about to about to just, what’s the term do a face plant or something, get pitched off the board. But it’s a pretty awesome…

Micheal:… At the that break normally you go right

Ruth: So at the break usually it’s a right but occasionally there’s a left and that’s good for you because you’re a goofy foot.

Michael: Muffled

Ruth: Right so there are rocks too on this beach at certain tides and so when you went left, getting carried on that really beautiful wave suddenly there’s the rocks right there so you were bailing with a purpose, not getting ditched by the wave.

Michael:… muffled

Ruth: Yeah, that year all of his friends were razzing him about that, giving him a hard time.

Maia: I’m sure they were. How could they resist [Laugh]

Ruth: So only recently and the person who took the photo was posting old retro photos that one came up and she put the story of what really happened corroborating Michael’s perspective [laugh].

Maia: You were actually narrowly avoiding certain doom.

Michael: I remember… muffled

Maia: What did he just say?

Ruth: He said he remembers talking to someone when he came out of the water and they were saying, “What the BLEEP were you thinking?”

Maia: Going left on that wave? [LAUGH] Yeah, if you look at the picture you can tell there’s a rock revealing itself at the bottom.

Maia: Alright so we were talking, Ruth was not here but we were talking about the time around your diagnosis and how you handled work and your insights about… Would you be willing to share any of that?

Ruth: So, you were diagnosed, you went in for some other reason you thought maybe pinched shoulder nerve that was affecting your snowboarding yeah and so you were diagnosed pretty quickly with ALS but you didn’t feel certain yet that that was a correct diagnosis so you didn’t want to tell anyone including me. But you definitely didn’t want to tell anyone at work. You wanted to just keep going until that was confirmed.

Michael:…

Ruth: Work is a big part of a man’s ego. You were afraid to give up the thing that you felt like…you were successful at. Right it took you a while to come to terms with the thought of not working so you continued working for two years without telling anyone at that work that you had ALS. In hindsight that’s the only thing you regret around that time is not not letting go of work sooner because you are you were working for the wrong reasons.

Michael: When I gave my notice we went right to Costa Rica.

Ruth: When you gave your notice. We went right to Costa Rica after that. {and you never went back]. And you never went back to work, you gave notice, yeah it’s a small town you saw people afterward and, yeah that was very… people were great, people were really supportive and that’s all good but I think that was probably a good way for you to do it rather than give notice and stay there and have to go through a lot of emotional goodbyes. It was easier to, you know, make that break, go away on a nice surf vacation and then come back and deal with the aftermath, yeah in a better place.

That was the trip after you left work though that’s true when you couldn’t surf just standing in the waves, the waves are so big that they were knocking you over. That was super hard, yeah.

Maia: Yeah, I mentioned to you when we were talking earlier is that out I’ve had to certain mysterious one of the reasons is as I told you before I told Michael undiagnosed situation, health challenge that I’ve been dealing with the last two years which has at times affected my ability to surf and I have been unable to surf really in the way that I have developed a taste for. And it’s, it’s been a really interesting transition of acceptance and embracing the mystery of it and not knowing what tomorrow is going to bring in and realizing that at some tomorrow every surfer will be done surfing. This is the nature of life and surfing is the best part of life and it really, it has been, well it’s been maddening and very sad at points for me to think about not being able to surf for you know a week or a month or however long it’s been. I’ve also found it really helpful to have had those, the lessons that surfing has taught me. Has that been true for you since not being able to surf?

Ruth: Surfing’s all about adapting to the situation. So being able to adapt and keep going forward. I mean, that’s what ALS is all about too. I mean, it’s all about adapting, and adapting.

Michael: muffled…

Ruth: [Laugh] I say that I can remember you saying early on that when you couldn’t surf any more was when you would be ready to let go and you don’t remember saying that and clearly, that hasn’t come to pass. But there were a lot of conversations, you know, soon after an ALS diagnosis about you know, you’re going to be going through this all of this, all of these, these losses, losses of abilities and losses of things that you used to enjoy so much.

And so we saw this film “Consider the Conversation” and it really is about end of life choices and there was this really just moving part about this person who had this notion of a list of 100 things, you write 100 things, you think of 100 things that you love and that you enjoy and as you age or have a debilitating disease you lose the ability to have or do those things and for each person the point at which your life is no longer meaningful, the number will be different, you know, like for somebody it might be if they can’t do 20 things on that list the rest of them aren’t enough to make life worthwhile, or that’s what you think at that point but for somebody else if they still have 1 thing on that list that they can still do they might want to stay alive. And so we were having those kind of conversations about what would the things on anybody list be? Which things would be at the top of the list? When would you really feel like life is no longer worth living? Is it when you can’t walk? When you can’t talk? When you can’t sing? When you cant eat by yourself? When you can’t surf, and I think that’s what I remember it was around the time the conversation about that movie and you were like, “Ugh, if I couldn’t surf, like I don’t know, I don’t know if I want to live and now we’re 5 or 6 years out from that and you no longer surf but you certainly, you’re living.

So you found that your list does have a lot of things on it besides surfing that you still want to live for. Cause I wonder if back at the time like before you lost the ability to surf you may have been imagining that, “Well, when I can’t surf, I can’t do this, I can’t do this, like I won’t be able to do so many things but it wasn’t that way. Surfing is a highly skilled endeavor, right, so when you lost the ability to surf you really could still do a lot of other things I mean you really started getting into the motorcycle after that. So but back then when you were thinking, “Oh, if I can’t surf I might not want to live.” you weren’t really envisioning all the other things that you still could do and also just the whole life of life with other people.

Michael:…

Ruth: That is a good point. Thank you honey?

Maia: What did he say?

Ruth: He told me that is a good point. Laugh

Michael:…

Ruth: Yeah, so you realized you had a passion for surfing but really surfing’s just part of your life and you’re realizing that you actually had a passion for life, surfing was just a part of that passion for life. And you still have that.

Michael: I still consider myself a surfer.

Ruth: You still consider yourself a surfer. Even though he’s not surfing he feels like he’s still a surfer because you’re still so in tune with the surf and the conditions. And many other things that surfing teaches are still a part of your life today.

Michael: Relevant

Ruth: Relevant to your life today as we are talking about before the patience, resilience bravery…

Ruth: He just had this interesting little observation the other day that I had never considered, he was saying that so, um with ALS when you lose muscle that includes tongue and throat and so swallowing can be a challenge and aspiration, choking can be a danger. So he does aspirate and choke a little bit sometimes and this is just such a strange connection he said that he feels like he’s able to get through that because of skills he learned from surfing when you get pounded and knocked under and your rolling around having to hold your breath underwater and stay calm and you know find your way through it and find your way up. That that skillset is what he uses to stay calm when he needs to clear his throat and he’s literally not breathing for a little bit because there’s an obstruction but he is able to maintain calm and not freak out because he learned that from doing it surfing.

Michael: muffled …

Ruth: Hold on, don’t panic.

Don’t hurry the moment

Ruth: Don’t hurry the moment it will pass.

Keep your calm so you’ll be there when it passes.

Michael: muffled …

Ruth: Keep your bearings. So, persistence, persistence obviously is a part of surfing you’re saying now with ALS and how it’s affected you, you have to be persistent just in your walking, just staying on your feet you have to be persistent and aware.

Michael: Determined

Ruth: Determined

Ruth: In surfing you have to be determined to get out through the waves.

Michael: Now… muffled … not let ALS rule my life.

Ruth: So now it’s the determination to not let ALS rule your life.

Michael: Right.

Ruth: I think balance too. I mean this isn’t a lesson like a cognitive lesson but it’a a body lesson that all the time spent on the surfboard, it’s so much about balance and the same with snowboarding, right? The balance and I wonder if, all of that time doing those sports where you’re getting off balance but you recover your balance— that’s what it’s all about because the medical people are amazed that you’re still on your feet. So I think it gave you some really great balance.

Maia: You were a pretty good surfer?

Michael: I think so

Ruth: He thinks so. In his own humble opinion. [LAUGH]

Maia: Very interesting. And Ruth you never wanted to surf? Did you try it?

Ruth: I never really tried much I mean I paddled around on a board and I didn’t have the persistence for it in Maine. I swim in the water in Maine but to be in the cold water in Maine also doing something really hard, I just, it didn’t call to me.

Maia: It didn’t sound fun.

Maia: As Micheal said earlier, motorcycling was his adaptation— the way he found to nurture his passion for life by setting out on adventures that challenge and inspire him. I asked Michael and Ruth to tell me a little more about Michael’s motivation for taking long trips on his bike to remote places like Novia Scotia and Hudson Bay where there’s no one would be around to help if he ran into trouble.

Ruth: He always wanted to do this motorcycle trip because you have to be independent and self sufficient, these backroads, you have to have fuel with you you have to have all your gear and your out in the middle of friggin nowhere all by yourself laugh. You wanted, he wanted to do it before he could not, I mean time is ticking, you know, with your physical abilities so…

Back then you were thinking that you might be dying in the hospital within a year or so, so you wanted to really get out there and challenge yourself physically before you did. Yeah So that’s why, was that you question about why he took that adventure?

Maia: Absolutely. Did that happen after you’d stopped surfing?

Michael: muffled …

Ruth: So he did, I think 3 really long, big, remote ones like that and then which might have overlapped with the time that you had to get done surfing because you took some falls on the motorcycle. So when he began falling on the motorcycle because he didn’t have the strength in his legs— when you come to a stop you gotta put your leg down— then he decided he wanted to continue motorcycling so his adaptation was to get a side car. And he still has, so when you got the motorcycle with sidecar you took trips with that too and one notable one when you got your BMW you went from here all the way across country by yourself to Arizona and back.

Maia: Wow!

Ruth: LAUGH Yeah, motorcycling was a passion for him too. And that continues so his motorcycle with sidecar is in a barn just down the road and he’s hoping to get it out any day now and see whether that’s still going to be a possibility this summer.

Maia: So I want to back up just a minute to when you were talking about how you still consider yourself a surfer. It sounded like what you were saying is you can be at the water and look at the waves and you still have a surfer’s relationship with them. You can still engage with them in that same way. And this is one of the ideas that has emerged over time as I’ve been doing these interviews and thinking more about Waves to Wisdom, is that on some level it is fundamentally a question about relationship and the practices that enhance certain kinds of relationships. And I think most of us, not just in this culture, but as humans we, in all relationships we really tend to get a little clingy and desperate and scared all the time. And I think that that in some ways, at least in this moment for me, one of the most inspiring parts of your story is that this fundamental part of your identity endures beyond anything that you can or can’t do with your body because it’s about your relationship with this thing, the ocean and all the things that it’s taught you. Is that a fair characterization?

Michael:… Absolutely

Ruth: Absolutely

Maia: Is here anything that you can think of that you’d like to add to that that I might have missed.

Ruth: To him it doesn’t feel like it’s been 5 years since he surfed. It’s in his mind, it’s in his heart, he still has a deep relationship with the ocean.

Intellectually you know that you cannot surf…

Michael: In my bones I feel like I’m still surfing.

Ruth: But in your bones you feel like you’re still surfing. That you don’t have to still be surfing to have a relationship and a connection to the ocean? Yeah. It’s like a lot of things that you have. For any body, for any human as you get older there are things that you did or you had that you can no longer do or have but they’re not erased entirely from your being. It’s still there, it’s still part of you, whether it’s the memories of it, the physical memory of it, or the things that you learned and took from it.

Maia: How long did it take you to get good? How long did it take until you felt you were good, I should ask?

Ruth: He probably felt like he was good right away. That’s his personality [laugh].

Maia: Is there anything else you would like to tell people about surfing, life, waves, anything?

Michael: I had a good partner.

Ruth: You had a good partner. Yeah, I think anybody in a good relationship with someone else, when that person has a passion, you support that passion.

Maia: Probably came back in a better mood than he left?

Ruth: Yeah! Definitely. And we all got to go on a lot of great beach trips.

Maia: Thank you both so much.

A lot of great beach trips could sound like a bunch of vacations, fun but fleeting. But Michael’s story seems to me a powerful demonstration of the theme I’ve found in my own life of outdoor pursuits and, more recently this dedication to an ocean-centered practice. Ours is a culture that values wellness and scientific research that supports it, sometimes to our peril. Everyone my age will remember the low fat orthodoxy of our youth and the processed, packaged fat-free foods that stocked the shelves of many of our pantries. There is plenty of new scientific research showing the benefits of activities in natural settings and I’ll post about some of that in the coming weeks. But Michael’s story is more persuasive to me that any research.

A passion for life that takes the form of devotion to a kind of fluid, fully embodied activity like surfing offers so many potential gifts of joy and wisdom, none of which are necessarily dependent on that ultimately undependable life circumstance, physical health.

For more information about coaching, our ocean-centered retreats, or to inquire about sponsoring this podcast, visit wavestowisdom.com

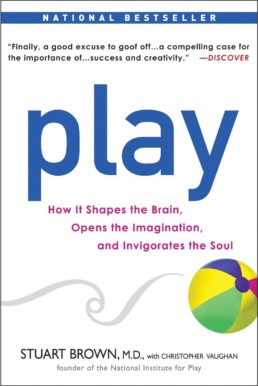

Playtime: Part 1

The changing circumstances of a dynamic, shifting environment of moving water and gathering or diminishing light… these periods of peak change are always an exercise in healing my frayed American relationship to time. Time is, after all, both the one material on which all my other endeavors, hopes, wishes, and lessons depend for their existence and the medium in which they are rendered.

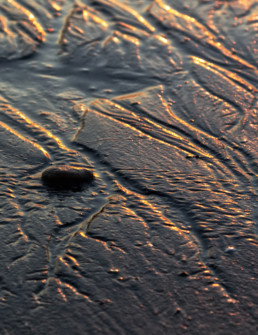

A few nights ago, I walked the short jungle path from my shack in Playa Guiones, Costa Rica to photograph in the day’s last light on the crescent shaped, white sand beach. As the scene grew redder by the passing minute and sinking sun, I watched a boy, dangling in the air facing the incoming breakers, held up by his strong young father’s hands. As each line of whitewater reached them the man swung the child into the wave in a dense cascade of spray, kicking, and laughter.

Last night, during a different sunset shoot, I saw two young girls scramble up a 5-foot rock wall from a clear tide pool. Atop what must have felt to them like a precipice, they reached for each other’s hands, then jumped. Crescendos of laughter lent cadence and rhythm to both their fall and landing. They plopped down and dug into the sand to scoop wet hands full. Flinging sprays and globs of sandy muck onto the rock wall and each other before bouncing up, they commenced a new cycle of climbing, jumping, flinging, laughing.

This morning, during sunrise, I rode faster, steeper waves than I would have dared when I first arrived here in Costa Rica a couple of months ago. Working hard to choose fun over fear, I paddled over the edge of one particularly large wave and, as I felt my feet find the board, I heard a hoot of encouragement from a young, male Costa Rican surf instructor. When kind of exchange happens I often feel a comforting happiness swelling the thrill of the ride from a deep, primal place, as though I’ve achieved some kind of tribal inclusion. Although unaware of the passing minutes, I spend a lot of time smiling out in the sun and have a world class wrinkle tan to prove it. I have surfed every day my energy allowed and for every second I dared to. No one had to suggest it was a good idea, nor did it take any will-power. I do wear a watch, a chronometer, to keep myself accountable to physical limits adrenaline and just so much fun might tempt me to ignore.

It is easy to be “disciplined” about “exercise” and put up with the adversity in the line-up (the occasional pummeling by whitewater, the risk of a crowd with many beginners, the exhausting nature of the endeavor) when there is the hovering promise— but never a guarantee— of sheer, unadulterated joy. As a matter of fact, the difficulties and occasional fright I feel surfing lend dimension to the bliss and turn it into a sacred, instructive kind of play. Perhaps the same is true for the swinging toddler and the jumping young girls? One thing’s for sure, none of us is counting the minutes.

The changing circumstances of a dynamic, shifting environment of moving water and gathering or diminishing light as the sun crests the mountains or sinks into the sea— these periods of peak change are always an exercise in healing my frayed American relationship to time. Time is, after all, both the one material on which all my other endeavors, hopes, wishes, and lessons depend for their existence and the medium in which they are rendered.

Looking around at the people on this beach, each in their way being playful, it seems we can feel time in our own bodies. We can know the reality of ephemeral happenings lived as we evolved to live them, immersed and fascinated by the world we inhabit and our unlikely existence as its sentient manifestations.

Sunsets and rises are a part of the day when the unidirectional arrow of time feels particularly speedy. Looking around on the beach with waxing or waning light, the planetary movement that gives our days their time renders each elapsing moment of life visible. Somehow this acute awareness of life-time passing never feels stressful and is often inspiring. I wonder if this is true because, at that beautiful hour, the lived experience between blindingly bright and blindingly dark is fleeting and so packed with visible change? It’s a kind of vision that allows us to lose track of the chronological minutes and feel time in the form of moving bodies of sun and earth, light and shadow, deepening or diminishing darkness. Looking around at the people on this beach, each in their way being playful, it seems we can feel time in our own bodies. We can know the reality of ephemeral happenings lived as we evolved to live them, immersed and fascinated by the world we inhabit and our unlikely existence as its sentient manifestations.

Something I’ve learned from watching the people I’ve guided into similarly playful, awe inspiring, sometimes challenging experiences is this: so often they lose track of what we usually think of as time. They emerge into some other deeper awareness of life’s steady, simultaneously cumulative and erasing movement. Each experience takes its rightful place as both a new moment lived and a time forever passed. It’s a way of sensing the contradictory nuance of how brief and full our life time is, or can be, if we cultivate our capacity to show up for it. We love economic metaphors so perhaps we could become more full, authentic participants in our time if we move from spending time to paying attention. This kind of attentive, body-grounded presence and the time perception it allows is a passage, like in music or literature, that moves you towards a concentrated capacity to sense life and the light that illuminates it. Then it becomes a passage, like a journey to another realm of feeling and, with practice, of knowing. I find this sort of ontological clarity and orientation, a creaturely comfort in physically being in one’s time, is most often within easy reach on the beaches I gravitate towards to play and work during these transitions into and out of the well-lighted world my diurnal eyeballs evolved to navigate.

And, at least here in Playa Guiones, I’m not alone. Sunsets in this coastal village are community playtime. People come out at this time of day to talk, to splash, meditate, dig, toddle, and crawl. Some of us come to surf or just to watch this display of time’s movement and be inspired and energized by it. At those moments, time is not our enemy.

I’ve come to believe that, if I am, if we are to have a fighting hope of healing our relationship to our own time, we need more words for the it, this stuff of our lives. The Greeks had at least two: chronos and kairos. Chronos is time as we generally think of it— the kind that can be counted and measured— seconds, minutes, hours, days, and years. Kairos is the sort of time we mean when we say the time is opportune or propitious, a moment (extended or fleeting) in which something must necessarily happen for it to happen at all. A deeper, qualitative kind of time, kairos evokes the layered, unknowable sequence of events and circumstances that must come together to make a time “right.”