To listen to the interview, scroll to the Player at the bottom of the page.

"... with ALS when you lose muscle that includes tongue and throat and so swallowing can be a challenge and aspiration, choking can be a danger. So he does aspirate and choke a little bit sometimes... he feels like he’s able to get through that because of skills he learned from surfing when you get pounded and knocked under and your rolling around having to hold your breath underwater and stay calm and you know find your way through it and find your way up."

~Ruth Coleman for Michael

Interview Transcript

Introductory note about this show: I know from soliciting feedback from subscribers that many of you all are reading the transcripts rather than listening to the recording. In this case, I hope you will listen to at least some of it. As I note in the interview, Waves to Wisdom is on a fundamental level, a multidisciplinary exploration of how we can deepen and enhance relationship. Listening to the exchange between Michael and Ruth’s voices is, to my heart and ear, more powerful than the content itself.

All of these interviews are edited (the initial conversations can extend over hours) and I do not, as a matter of course, ask interviewees how they feel about the edited conversation. Rather, I ask for their trust up front. But Michael was hesitant about whether he wanted his voice out in the world and I wanted to make doubly sure he was happy with the result. He didn’t love the sound of his voice but, as he astutely noted, who does?

Transcript

Intro: My name is Maia Dery. This episode is part of a series called the Waves to Wisdom Interviews. The project is a simple one. I seek out people I admire, surfers who seem to me to have ocean centered wisdom practices.

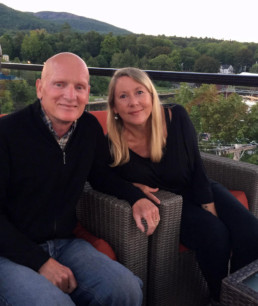

Usually, I ask them to share a surf session or two and, after we’ve ridden some waves together, talk to me about their oceanic habits, about surfing, work, meaning, anything that comes up. All of the episodes so far have spoken to the benefits and beauty of a long, intimate relationship between two bodies, the surfer and the ocean. This one’s a little different. Michael Coleman has been a surfer for more than 40 years. Just 8 years ago, he was diagnosed with a debilitating illness meant he had to face letting go of riding waves and, eventually, getting in the water at all.

But the waves continue to infuse his life with wisdom, both practical and profound. He and his wife Ruth Coleman were generous enough to share some of Michael’s story and, although we couldn’t be in the ocean in the same place and time, both Colemans left me so deeply inspired I’ve carried them with me into almost every wave I’ve ridden since our time together.

Oceanic wisdom comes in many forms. In her book, A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit wrote about the way hermit crabs look for shells that weren’t really made for them and then mold their soft bodies to fit the shape of them. A set of internal claws clings to the shell while the external claws do their work in the world. She goes on,

“Many love stories are like the shells of hermit crabs, though others are more like chambered nautiluses, whose architecture grows with the inhabitant and whose abandoned smaller chambers are lighter than water and let them float in the sea.”

My time with the Colemans told two love stories, their own and Michael’s long passion for living life to the utmost. Welcome to Waves to Wisdom.

Maia: If you are comfortable with it would you tell us your name, your age, and how long you’ve been surfing?

Michael: My name is Michael Coleman I’m 60 years old I’ve been surfing since 1975

Maia: Fantastic — and where did you first learn to surf?

Michael then Ruth:

Ogonquit Beach [Ogonquit Beach] Maine [Maine] okay and so you, you were a young man at that point?

Michael: I think my junior or senior year in high school.

Ruth: His junior or senior year in high school as a summer job he was a lifeguard. So I think you were probably 17? 16, 17, when he first started.

Maia: Okay. And this, as I was just telling the two of you all, this is an unusual interview because usually there two of us. Do you want to tell us why there are three of us?

Michael: Well, I can’t speak very well because I have ALS.

Ruth: So he said as you can probably hear I can’t speak very well because I have ALS so Ruthy is speaking for me, or can understand me pretty well. So I’m Ruth, Michael’s wife, we’ve known each other since before he was 17 [laugh] [Wow, I didn’t know that part of the story] so you can do the math! and that that’s why I’m good at understanding him.

Maia: Probably in lots of ways. Not just this one…

Ruth: Yeah.

Maia: And so, I believe I recall you saying you surfed until about five years ago? [yes] Yes, until about five years ago? OK, and did, I mean starting to surf at 16 or 17 you know, one is not fully formed, certainly, at that age, do you feel like surfing impacted the adult that you grew into?

Michael: Yes.

I think that surfing was the impetus to travel.

Ruth: It was the, gave him the impetus to travel. Made him want to travel, to go other places for surfing…. Learning about other cultures. So surfing gave you the desire to travel and then traveling gave you the desire to learn more about other cultures. [mmm hm] (5:04) You like to go to places where surfing is available but it’s not like the only thing the place is known for. It doesn’t overwhelm the location, what was already there. Yeah.

Maia:

So we’re in your living room of your beautiful new house, this is your downsizing house in Rockport Maine. Rockport’s not known for surfing either.

Ruth: [Laugh] No

Maia: How did you wind up choosing Rockport?

Ruth: Michael took a motorcycle trip. Barry had given him um just some little ad for a piece of land or something that was randomly in Rockport. I had never really been here other than driving through. And Michael took a motorcycle ride and came up and looked at it and put some money down [Oh my goodness, really?] on the property and we were married then and we were thinking about building or buying a house but we hadn’t really been thinking about that and we were thinking about moving out of Southern Maine because it was just going through a lot of changes at that time that explosion of condos and we just felt, I dunno, it didn’t feel right to us. But so yeah that was kind of random so he put a down payment on that land and continued paying for it for about a year and then the year after we got married we, I applied for jobs and we came up here and built our first house.

Maia: Wow. So you had to travel to surf? Did you get to do that often?

Michael: … It felt like it

Ruth: It felt like it. At that time you were working for yourself so he had flexibility.

Maia: And how often do you think you went down to surf?

Michael: …

Ruth: Whenever there was… when the waves were good… that’s the whole thing about the WeatherBand. That’s why we were always listening to the NOAA WeatherBand.

https://www.weather.gov/ama/nwr

Maia: Will you tell that story?

Ruth: LAUGH Just that, before the Internet, the way that you’d know about surf coming in Maine would be to listen to the NOAA weather and it would… surfers would be thinking ahead because certain conditions that NOAA would tell you about would indicate whether a swell and then waves were coming so Michael would just listen to that all the time. He’d fall asleep listening to it. [Michael muffled]

Ruth: Oh it was an automated voice.

Michael: On a loop.

Ruth: On a loop, yeah so it was annoying to everybody else but Michael loved listening to that LAUGH.

Maia: So did you go on some surf related adventures in your 20s before your kids came along?

Ruth: We started with international trips actually when we had kids.

Maia: For surfing?

Ruth: Yeah. Well, Dad, Michael… (laugh) all of our traveling were to locations where there were beaches LAUGH.

Maia: There were no family trips that didn’t involve at least some surf?

Michael: Why would there be?

Ruth: Why would there be? [LAUGH] Also, it just kind of made sense because living in Maine when you want to go away in the winter so where you want to go is someplace that’s warm that worked and in the summer we didn’t want to go away from Maine because that’s when Maine’s great.

Michael: Muffled

Ruth: Yeah, there were— we saw many other things as a result of surf trips, absolutely.

Maia: It was a force for good.

Ruth: Yeah, he would get up early and go surfing and there were still lots of family adventures.

Maia: One of the premises of this project is my untested theory that for some people who have this regular practice of surfing, of interacting with the ocean in this completely immersive, expansive way— that it helps them figure their life out. That it can make them better people or put them in touch with something bigger than themselves. Do you think, am I onto something? Is there any part of that that seems valid to you?

Michael: …Yes.

Ruth: Can I just say something while you’re thinking. It has struck me now in retrospect— I didn’t really get it at the time, but Michael used to talk about surfing as just being really pure and clean and he would feel really clean and his mind would feel really clean and it… In retrospect I realize it was like, before the trendiness of mindfulness and “ in the moment” that was exactly how you would describe things, is that you liked it because you were only focused on that because you have to you have to be paying attention to the, you know, the waves and the sets and what’s happening with the weather and all of that. And so, like I didn’t— that didn’t register to me at the time because it was before all that talk about mindfulness and being in the moment. But now in retrospect I look back and I think that’s how you always talked about it. That’s what you liked about it that you would be out there, you know, not necessarily alone because there’s other people surfing but you would be so intensely focused that sort of like wiped your mind clear.

Maia : Is there any other way in which it had practical or impractical benefits?

Ruth: Let me just make sure I got it so you’re saying in surfing is the last failure, you fall and you fall and you fall you fall again, and you have to get back up. Nobody is telling you you have to get back up but you just, you do it. And so the feeling of, then when you do get back up after all those falls and then you have success, that’s a really powerful feeling, that resilience.

Michael: muffled

Ruth: It changes you? [Michael muffled] It teaches you all those things like patience and to keep trying, getting up again. And those apply outside that’s what you said at the end there. That that resilience, that keep trying even when you’ve been knocked down that that… somehow you internalize that you feel like you applied it in other places.

Michael: … even today [even today] I think that in my current situation…

Ruth: In your current health situation. That resilience and ability to adapt.

Michael: Has helped me

Ruth: Has helped you with ALS

Maia: How long’s it been since you’ve been able to surf?

Ruth: 5 or 6 years and he was diagnosed with ALS more than 8 years ago. So you still surfed for a couple of years after you had ALS but you weren’t as greatly affected by it as you are now. As the progression continued it got harder.

Michael: I remember…

Ruth: He remembers a time in Costa Rica after he had ALS when his legs weren’t affected that badly but one of his arms in particular was and he felt like he was paddling in circles because one arm was weak one arm was strong. And how did that feel?

[LAUGH] He said at that time he was more focused on getting out to the waves before Carl, one of his buddies, so that bothered you? For that reason? Ok.

Maia: Are there any other ways, let’s think before ALS that you think this surfing might have had a positive influence on your life?

Ruth: Can I say one while you’re thinking? I think that you you just always had tremendous energy I think it was an outlet for your energy. I think I don’t know if you you feel that way about it but… and then looking back at thinking about how you said it that’s just what you like about it how it just kind of wiped your mind clean and I think it was that that you know that it takes a lot of physical effort to surf but it also had that meditative quality and that you— I just remember you being almost like driven to get there and then you would just feel like cleansed, or something after you, after you did it. And you always did a lot of sports remember? So and I think then when you had less opportunity for sports, team sports kind of in your life that surfing, fulfilled that need for that physical activity but it also was having that other mindfulness, meditative effect on you. When you could first see the waves

Michael: Oh my God, Oh my God, Oh my God…

Ruth: You couldn’t wait.

Michael: muffled…

Ruth: You could get out of your truck and be in the water in minutes.

Michael: muffled…

Ruth: Someone would say. “What do you think Mike?” Looking at the surf and he’d already be moving and saying “I’m not going to think about it I’m just getting in the water.”

Maia: So earlier you got out a copy of Surfer Magazine from 1990, was it? [uh hm] and there in the pages of Surfer Magazine is a picture of Michael Coleman on a huge, looks like about to be barreling left, what’s the story of that?

Michael: I will let Ruth tell it.

Ruth: I don’t really know the story just that you were out there and someone was taking pictures because it was pretty epic surf for Maine and that the picture that got into Surfer Magazine the caption that went with it was something like, “Mike Coleman biting it Maine style” because it looks like he’s about to about to just, what’s the term do a face plant or something, get pitched off the board. But it’s a pretty awesome…

Micheal:… At the that break normally you go right

Ruth: So at the break usually it’s a right but occasionally there’s a left and that’s good for you because you’re a goofy foot.

Michael: Muffled

Ruth: Right so there are rocks too on this beach at certain tides and so when you went left, getting carried on that really beautiful wave suddenly there’s the rocks right there so you were bailing with a purpose, not getting ditched by the wave.

Michael:… muffled

Ruth: Yeah, that year all of his friends were razzing him about that, giving him a hard time.

Maia: I’m sure they were. How could they resist [Laugh]

Ruth: So only recently and the person who took the photo was posting old retro photos that one came up and she put the story of what really happened corroborating Michael’s perspective [laugh].

Maia: You were actually narrowly avoiding certain doom.

Michael: I remember… muffled

Maia: What did he just say?

Ruth: He said he remembers talking to someone when he came out of the water and they were saying, “What the BLEEP were you thinking?”

Maia: Going left on that wave? [LAUGH] Yeah, if you look at the picture you can tell there’s a rock revealing itself at the bottom.

Maia: Alright so we were talking, Ruth was not here but we were talking about the time around your diagnosis and how you handled work and your insights about… Would you be willing to share any of that?

Ruth: So, you were diagnosed, you went in for some other reason you thought maybe pinched shoulder nerve that was affecting your snowboarding yeah and so you were diagnosed pretty quickly with ALS but you didn’t feel certain yet that that was a correct diagnosis so you didn’t want to tell anyone including me. But you definitely didn’t want to tell anyone at work. You wanted to just keep going until that was confirmed.

Michael:…

Ruth: Work is a big part of a man’s ego. You were afraid to give up the thing that you felt like…you were successful at. Right it took you a while to come to terms with the thought of not working so you continued working for two years without telling anyone at that work that you had ALS. In hindsight that’s the only thing you regret around that time is not not letting go of work sooner because you are you were working for the wrong reasons.

Michael: When I gave my notice we went right to Costa Rica.

Ruth: When you gave your notice. We went right to Costa Rica after that. {and you never went back]. And you never went back to work, you gave notice, yeah it’s a small town you saw people afterward and, yeah that was very… people were great, people were really supportive and that’s all good but I think that was probably a good way for you to do it rather than give notice and stay there and have to go through a lot of emotional goodbyes. It was easier to, you know, make that break, go away on a nice surf vacation and then come back and deal with the aftermath, yeah in a better place.

That was the trip after you left work though that’s true when you couldn’t surf just standing in the waves, the waves are so big that they were knocking you over. That was super hard, yeah.

Maia: Yeah, I mentioned to you when we were talking earlier is that out I’ve had to certain mysterious one of the reasons is as I told you before I told Michael undiagnosed situation, health challenge that I’ve been dealing with the last two years which has at times affected my ability to surf and I have been unable to surf really in the way that I have developed a taste for. And it’s, it’s been a really interesting transition of acceptance and embracing the mystery of it and not knowing what tomorrow is going to bring in and realizing that at some tomorrow every surfer will be done surfing. This is the nature of life and surfing is the best part of life and it really, it has been, well it’s been maddening and very sad at points for me to think about not being able to surf for you know a week or a month or however long it’s been. I’ve also found it really helpful to have had those, the lessons that surfing has taught me. Has that been true for you since not being able to surf?

Ruth: Surfing’s all about adapting to the situation. So being able to adapt and keep going forward. I mean, that’s what ALS is all about too. I mean, it’s all about adapting, and adapting.

Michael: muffled…

Ruth: [Laugh] I say that I can remember you saying early on that when you couldn’t surf any more was when you would be ready to let go and you don’t remember saying that and clearly, that hasn’t come to pass. But there were a lot of conversations, you know, soon after an ALS diagnosis about you know, you’re going to be going through this all of this, all of these, these losses, losses of abilities and losses of things that you used to enjoy so much.

And so we saw this film “Consider the Conversation” and it really is about end of life choices and there was this really just moving part about this person who had this notion of a list of 100 things, you write 100 things, you think of 100 things that you love and that you enjoy and as you age or have a debilitating disease you lose the ability to have or do those things and for each person the point at which your life is no longer meaningful, the number will be different, you know, like for somebody it might be if they can’t do 20 things on that list the rest of them aren’t enough to make life worthwhile, or that’s what you think at that point but for somebody else if they still have 1 thing on that list that they can still do they might want to stay alive. And so we were having those kind of conversations about what would the things on anybody list be? Which things would be at the top of the list? When would you really feel like life is no longer worth living? Is it when you can’t walk? When you can’t talk? When you can’t sing? When you cant eat by yourself? When you can’t surf, and I think that’s what I remember it was around the time the conversation about that movie and you were like, “Ugh, if I couldn’t surf, like I don’t know, I don’t know if I want to live and now we’re 5 or 6 years out from that and you no longer surf but you certainly, you’re living.

So you found that your list does have a lot of things on it besides surfing that you still want to live for. Cause I wonder if back at the time like before you lost the ability to surf you may have been imagining that, “Well, when I can’t surf, I can’t do this, I can’t do this, like I won’t be able to do so many things but it wasn’t that way. Surfing is a highly skilled endeavor, right, so when you lost the ability to surf you really could still do a lot of other things I mean you really started getting into the motorcycle after that. So but back then when you were thinking, “Oh, if I can’t surf I might not want to live.” you weren’t really envisioning all the other things that you still could do and also just the whole life of life with other people.

Michael:…

Ruth: That is a good point. Thank you honey?

Maia: What did he say?

Ruth: He told me that is a good point. Laugh

Michael:…

Ruth: Yeah, so you realized you had a passion for surfing but really surfing’s just part of your life and you’re realizing that you actually had a passion for life, surfing was just a part of that passion for life. And you still have that.

Michael: I still consider myself a surfer.

Ruth: You still consider yourself a surfer. Even though he’s not surfing he feels like he’s still a surfer because you’re still so in tune with the surf and the conditions. And many other things that surfing teaches are still a part of your life today.

Michael: Relevant

Ruth: Relevant to your life today as we are talking about before the patience, resilience bravery…

Ruth: He just had this interesting little observation the other day that I had never considered, he was saying that so, um with ALS when you lose muscle that includes tongue and throat and so swallowing can be a challenge and aspiration, choking can be a danger. So he does aspirate and choke a little bit sometimes and this is just such a strange connection he said that he feels like he’s able to get through that because of skills he learned from surfing when you get pounded and knocked under and your rolling around having to hold your breath underwater and stay calm and you know find your way through it and find your way up. That that skillset is what he uses to stay calm when he needs to clear his throat and he’s literally not breathing for a little bit because there’s an obstruction but he is able to maintain calm and not freak out because he learned that from doing it surfing.

Michael: muffled …

Ruth: Hold on, don’t panic.

Don’t hurry the moment

Ruth: Don’t hurry the moment it will pass.

Keep your calm so you’ll be there when it passes.

Michael: muffled …

Ruth: Keep your bearings. So, persistence, persistence obviously is a part of surfing you’re saying now with ALS and how it’s affected you, you have to be persistent just in your walking, just staying on your feet you have to be persistent and aware.

Michael: Determined

Ruth: Determined

Ruth: In surfing you have to be determined to get out through the waves.

Michael: Now… muffled … not let ALS rule my life.

Ruth: So now it’s the determination to not let ALS rule your life.

Michael: Right.

Ruth: I think balance too. I mean this isn’t a lesson like a cognitive lesson but it’a a body lesson that all the time spent on the surfboard, it’s so much about balance and the same with snowboarding, right? The balance and I wonder if, all of that time doing those sports where you’re getting off balance but you recover your balance— that’s what it’s all about because the medical people are amazed that you’re still on your feet. So I think it gave you some really great balance.

Maia: You were a pretty good surfer?

Michael: I think so

Ruth: He thinks so. In his own humble opinion. [LAUGH]

Maia: Very interesting. And Ruth you never wanted to surf? Did you try it?

Ruth: I never really tried much I mean I paddled around on a board and I didn’t have the persistence for it in Maine. I swim in the water in Maine but to be in the cold water in Maine also doing something really hard, I just, it didn’t call to me.

Maia: It didn’t sound fun.

Maia: As Micheal said earlier, motorcycling was his adaptation— the way he found to nurture his passion for life by setting out on adventures that challenge and inspire him. I asked Michael and Ruth to tell me a little more about Michael’s motivation for taking long trips on his bike to remote places like Novia Scotia and Hudson Bay where there’s no one would be around to help if he ran into trouble.

Ruth: He always wanted to do this motorcycle trip because you have to be independent and self sufficient, these backroads, you have to have fuel with you you have to have all your gear and your out in the middle of friggin nowhere all by yourself laugh. You wanted, he wanted to do it before he could not, I mean time is ticking, you know, with your physical abilities so…

Back then you were thinking that you might be dying in the hospital within a year or so, so you wanted to really get out there and challenge yourself physically before you did. Yeah So that’s why, was that you question about why he took that adventure?

Maia: Absolutely. Did that happen after you’d stopped surfing?

Michael: muffled …

Ruth: So he did, I think 3 really long, big, remote ones like that and then which might have overlapped with the time that you had to get done surfing because you took some falls on the motorcycle. So when he began falling on the motorcycle because he didn’t have the strength in his legs— when you come to a stop you gotta put your leg down— then he decided he wanted to continue motorcycling so his adaptation was to get a side car. And he still has, so when you got the motorcycle with sidecar you took trips with that too and one notable one when you got your BMW you went from here all the way across country by yourself to Arizona and back.

Maia: Wow!

Ruth: LAUGH Yeah, motorcycling was a passion for him too. And that continues so his motorcycle with sidecar is in a barn just down the road and he’s hoping to get it out any day now and see whether that’s still going to be a possibility this summer.

Maia: So I want to back up just a minute to when you were talking about how you still consider yourself a surfer. It sounded like what you were saying is you can be at the water and look at the waves and you still have a surfer’s relationship with them. You can still engage with them in that same way. And this is one of the ideas that has emerged over time as I’ve been doing these interviews and thinking more about Waves to Wisdom, is that on some level it is fundamentally a question about relationship and the practices that enhance certain kinds of relationships. And I think most of us, not just in this culture, but as humans we, in all relationships we really tend to get a little clingy and desperate and scared all the time. And I think that that in some ways, at least in this moment for me, one of the most inspiring parts of your story is that this fundamental part of your identity endures beyond anything that you can or can’t do with your body because it’s about your relationship with this thing, the ocean and all the things that it’s taught you. Is that a fair characterization?

Michael:… Absolutely

Ruth: Absolutely

Maia: Is here anything that you can think of that you’d like to add to that that I might have missed.

Ruth: To him it doesn’t feel like it’s been 5 years since he surfed. It’s in his mind, it’s in his heart, he still has a deep relationship with the ocean.

Intellectually you know that you cannot surf…

Michael: In my bones I feel like I’m still surfing.

Ruth: But in your bones you feel like you’re still surfing. That you don’t have to still be surfing to have a relationship and a connection to the ocean? Yeah. It’s like a lot of things that you have. For any body, for any human as you get older there are things that you did or you had that you can no longer do or have but they’re not erased entirely from your being. It’s still there, it’s still part of you, whether it’s the memories of it, the physical memory of it, or the things that you learned and took from it.

Maia: How long did it take you to get good? How long did it take until you felt you were good, I should ask?

Ruth: He probably felt like he was good right away. That’s his personality [laugh].

Maia: Is there anything else you would like to tell people about surfing, life, waves, anything?

Michael: I had a good partner.

Ruth: You had a good partner. Yeah, I think anybody in a good relationship with someone else, when that person has a passion, you support that passion.

Maia: Probably came back in a better mood than he left?

Ruth: Yeah! Definitely. And we all got to go on a lot of great beach trips.

Maia: Thank you both so much.

A lot of great beach trips could sound like a bunch of vacations, fun but fleeting. But Michael’s story seems to me a powerful demonstration of the theme I’ve found in my own life of outdoor pursuits and, more recently this dedication to an ocean-centered practice. Ours is a culture that values wellness and scientific research that supports it, sometimes to our peril. Everyone my age will remember the low fat orthodoxy of our youth and the processed, packaged fat-free foods that stocked the shelves of many of our pantries. There is plenty of new scientific research showing the benefits of activities in natural settings and I’ll post about some of that in the coming weeks. But Michael’s story is more persuasive to me that any research.

A passion for life that takes the form of devotion to a kind of fluid, fully embodied activity like surfing offers so many potential gifts of joy and wisdom, none of which are necessarily dependent on that ultimately undependable life circumstance, physical health.

For more information about coaching, our ocean-centered retreats, or to inquire about sponsoring this podcast, visit wavestowisdom.com

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 40:31 — 37.1MB) | Embed

Subscribe: Google Podcasts | Email | RSS