Interview: Brad Turner

To listen to the interview, scroll to the Player at the bottom of the page.

I think will be very beneficial for everybody to take a look at the ocean, smell it, listen to if you're brave enough stick your toes in it. It will surprise you. There are some people who have a lot of fears about it but I believe in in learning about dangerous things that you deem fearful. You can go far. With knowledge there comes power. so a healthy education about the ocean with would definitely be a first step I would suggest. Theres a lot of learning to do but comes with steps or waves, if you if you will.

~Brad Turner

Photos of Brad courtesy of Lesley Gourley at https://www.photohunter.net/

Show Notes

Surfrider Foundation Activist Spotlight on Rhonda Harper and Black Girls/Inkwell Surf

Reuters Article on Solidarity In Surf

2021 NY Times Article about how black-owned coastal property and generational wealth were stolen

Psychology Today article about the benefits of Surf Therapy for PTSD

“On Being White and Other Lies” 1984 Essay by James Baldwin

A thought-provoking article on whiteness by a white woman

Blue Mind Research and References

Interview with Blue Mind instigator Dr. Wallace J Nichols on The Unmistakable Creative

*An update on Brad’s important work:

Brad has gone on temporary hiatus in his work with Black Girls Surf and Inkwell Surf. Check his Instagram for updates! In the meanwhile, this organization and the others listed above continue the inspiring and empowering work of addressing historical inequities and bringing equal access to the waves.

Transcript

Brad:

I think will be very beneficial for everybody to take a look at the ocean, smell it, listen to if you’re brave enough stick your toes in it. It will surprise you. There are some people who have a lot of fears about it but I believe in in learning about dangerous things that you deem fearful. You can go far. With knowledge there comes power. so a healthy education about the ocean with would definitely be a first step I would suggest. Theres a lot of learning to do but comes with steps or waves, if you if you will.

Intro

Maia: We are deep in the winter of the Great Pandemic. We are losing so much but we are also learning and growing in ways that seem long overdue and right on time. The same week in which I’m recording this introduction, Brad Turner and I did what a zillion other people did, we logged onto a Zoom call. It was a conversation that came about because Brad was and is a generous teacher and collaborator. He’s also walking around with one of the biggest hearts I’ve encountered in the world of ocean-loving humans. The particular Zoom was the latest step in a journey we’d just begun earlier this year, when we recorded this interview. On my Zoom screen were members of the Surfrider Foundation from all over the country logged on for a discussion with historian Scott Laderman author of the book Empire in Waves: A Political History of Surfing. For those of you who don’t know much about Surfrider, here is the organization’s mission statement:

The Surfrider Foundation is dedicated to the protection and enjoyment of the world’s ocean, waves and beaches, for all people, through a powerful activist network.

This conversation with Dr. Laderman was the second in an ongoing series Brad and I are organizing through our local Surfrider chapter and putting up on a YouTube channel for all to learn from.* We’re hoping to talk with scholars and artists, filmmakers and poets, and any other humans whose work can help all of us who love the ocean understand “access” in ways that are more cognizant of our country’s history at home and abroad and the ways the politics of whiteness have impacted access to the places we ocean lovers hold dear.

During one moment in a rich and informative talk Dr. Laderman discussed the way localism, the tendency of surfers to keep their own line-ups for and to themselves, reinforces white supremacy and someone asked him, what should be put in its place. He said, I don’t want to sound all airy fairy but we could just be nice to one another. Later he said (I’m paraphrasing) we need to enter these surfing spaces with reverence for where we are in this moment, mindful and informed about our past, so that we can be effective stewards of the experiences open to future generations.

With knowledge, comes power. Brad Turner has a tremendous amount of both to offer. Welcome to Waves to Wisdom.

Brad: My name is Bradley Turner. I am 38 and I have been surfing for going on 21 years.

Maia: Wonderful! We are on your front porch near Carolina Beach [correct] where we have surfed now a few beautiful mornings together. We had some good days— one of them I had to overcome terror more than once.

Brad: It’s okay, it comes…

Maia: Okay good so that there are so many exciting things about your life and your relationship to the ocean I hope we can get into but would you start by telling us a little bit about this nonprofit organization you are instrumental in. And my understanding is there it basically has two names two different legs of the body, if you could tell us little bit about that.

Brad: Sure I run the East Coast variation of Inkwell Surf which is based out of Santa Monica, California. Additionally Black Girl Surf, and we deal with coaching and mentorship for the younger kids and we also provide a release for them in the ocean and just a place where they can discuss how they feel will and have an opportunity to see things that they normally wouldn’t see.

Maia: And are these primarily children of color?

Brad: They are.

Maia: Okay and we’re in North Carolina and I started to surf, now it’s 14 years ago, and I played sports growing up in North Carolina and one of the first things I noticed when I entered what I thought of as a sporting space— I’ve come to understand it as something much more akin to a religious order [definitely] almost with a discipline and a worldview but at that point I was thinking of it as a sport and I noticed right away that unlike almost any other sports environment that I had been in, there were almost no people of color in the lineup.

Brad: I can agree.

Maia: And that, it was startling to me and set me on this path of figuring out why? Why that happened and I hope we can talk more about the ways that you have been working to address that disparity and and some of the history that got us to this conundrum but first, please would you tell everybody about how you started out your adventure as a surfer? Brad: I started my adventure as a surfer back in the year of 2001 to deal with what I was experiencing at the time in the military at Camp Lejeune which is in Jacksonville, North Carolina. The first place I surfed was on base at Onslow Beach. That, that is my home break. At the time I was bored in the barracks, it was a hot summer and a few of my friends, we decided to go out to Onslow Beach and I had taken a boogie board and ridden my first wave. I had never seen the ocean, mind you…

Maia: Wow! How old were you at this point? Brad: I want to say I was 17 at the time and that one that one moment it, it replays as if I’d press rewind over and over again. I’m sure like every other surfer they remember that that first wave it was magical. I took off on, on a boogie board and I’ve never stopped since. LAUGH

Maia: So you took off on that first magical wave on Onslow Beach— Were you a strong swimmer at that point?

Brad: I’ve always been a strong swimmer. I played in pools as a kid. Eventually in middle school to high school I was a maintenance man apprentice and began to work on pools with the chemicals and such and cleaning it and also enjoying the luxury of swimming in it. So, yes I’ve always been drawn to the water in one way, shape, or form. It’s always been a place where I’ve felt comfortable.

Maia: OK, good so you’re in Camp Lejeune, you take off on that wave, and did you know right then that you were going to come back?

Brad: I was hooked! I think Kelly Slater termed it once, it’s like joining the Mafia, once you’re in you’re never getting out [LAUGH]. Yeah, I was hooked for life at that point.

Maia: And did you, did you have friends who you were in the military with who were standup surfing at that point who you started to go with? Brad: I unknowingly found out that America’s best and brightest, the tip of the spear as we say in the military, I was, I was surfing around them. I slowly learned their names and their stories. Most of them were special operators and I learned that that’s how they be compressed. They did their job for America and they came home and surfed. Many of them are still my friends and we all surf to help deal with her different paths and journeys in life.

Maia: Interesting! I’ve never been in the military, I do have some— my uncle was a career Navy enlisted and then officer and it has always struck me that for many people who serve especially for more than just a couple years that there’s they’re repeated traumas inherent in the job description and we I mean we have with all sorts of developing and ongoing research showing that surfing is a uniquely or at least exceptionally effective way of dealing with trauma. So it sounds like you just what happened into this community who had figured this out for themselves?

Brad: Correct and it just so happened that drawing to become a Navy corpsman which is the individuals who are attached to the Marines— from the Army would call us the medic. We’re there for medical attention, for, in the field, religious purpose and so on and so forth. And it just so happens that, you know, we were healing together in the water— doc and Marines— we were redoing it together, on the same journey, healing together. Not knowing the terminology at the time but we were, were definitely on the same vibration.

Maia: You weren’t talking about it you were just doing it.

Brad: Correct!

Maia: And how long was that period of your life that you were surfing at Onslow Beach and serving as a Navy Corpsman?

Brad: I served off and on entirely throughout the military for five and half years.

Maia: And did you grow up in North Carolina?

Brad: I did not. I was born in Canton, Ohio— football Hall of Fame! Just about when I was two or three, my mother and I, we moved down to Georgia from Georgia to the military from Norcross, Georgia.

Maia: So you were in the military for five and half years, you learned how to surf with, it turned out people who form the tip of the spear [correct]? Fascinating! And then you transitioned out of the military…

Brad: I did. The transition was a little Rocky, to say the least. I was dealing with a lot at the time: divorce, getting out of the military, moving away from that dynamic and learning how to be a civilian again. All those things culminating together different. I can say that throughout that surfing definitely kept me afloat, as it were, and I can go even further and say that it, it went as far as saving my life [really?]. Yes, yes.

I’s been instrumental in many points that I‘ve been very much at the bottom of the barrel it is definitely been my, my place of salvation. Yeah, I don’t know where I would be without surfing if we were to to be perfectly honest and upfront about it. Right now, if I want to think about it I can’t I can’t pinpoint where I would be without surfing life so I’m pretty thankful, very grateful. It has me or talking to you!

Maia: Oh my goodness, yes! And I am so grateful for being able to be here talking to you and I never would’ve found you with, without surfing myself.

So, as far as I can tell, the primary audience for these interviews is not surfers and one of the reasons that I love doing this podcast is that I’ve spent— I’m 54 years old at this point and I have spent might my adult life on the very edges of grown-up employment And as many surfers do and even before I was surfing I always knew that I needed to have the what we think of is the real-world aspects of my life which basically means the economic aspects of my life. that those parts of existence needed to not undermine my relationship with the more than human world in my ability to be active in and learning from it. So, one of the great parts about getting older is that you start to understand what you have to offer in new ways and and I’ve come to believe at this point with the zeal of the evangelical that it’s not just we as individuals who need to learn how to work less and play more, and be in our bodies, and have relationships with the more than human world, it’s not just we as individuals who need that, although we desperately do, it’s actually the entire planet that needs us to [oh, yes] to temper our priorities with these relationships in this web of life [definitely].

So, I’m very interested in how you would describe the value, I mean, you’re really clear about saying. “If it weren’t for surfing, I don’t know where I would be. I think it could’ve been really bad. It saved my life.” [Right] How did it do that?

Brad: I don’t know how to speak outside of surfing [Go ahead. please do] so I apologize for those who do not surf. It’s, it’s been basically an ebb and flow, a tidal adventure, drawn by the moon if we’re to go that far!

Maia: Yes, please let’s go all the way!

Brad: Yes it’s um… it’s been very beneficial definitely when I got out there was a veil that was lifted from my eyes as a African-American who served our country I started to see and feel in the real world that, what I fought for as a black person, I didn’t feel— I don’t know how to describe it, the same when I got out but my surfboard in the ocean it kept me balanced throughout the waves of difficulty that I experience. Even with people with different viewpoints I’ve surfed with, been best friends and had deep discussions in and out of the water which I think of a lot of the world needs right now. I’ve sat on the beach Onslow Beach of Carolina Beach of Wrightsville Beach of many beaches and talked to people who are real who they have real stories to their life, purpose. The ocean despite whether they surf or not allow some the release what they may be holding inside. I mean I’ve been lucky enough to be a surfer in and all of that happened in the water and I get to ride the, you know everlasting vibration starting at one point with wind and forming a wave. I’m grateful I hope that everybody can discover the, the blue mind, if you will, be able to apply it to their life and heal maybe I can help you I would love to.

Maia: yes I think you can help a great many people and that will be sure and put up a link to J Nichols’ book Blue Mind which you and I both read and less it is essentially the idea is that just being near the water heater have to be in it for the surfboard but just looking at the lake looking at the creek even looking at a photograph of the water can lower your blood pressure and chill you out. Brad: yes

Maia: Okay so you were in the military and you had one idea of the America that you were serving [correct]. You left the military and what I heard you say was that America turned out to not exist outside of the institution of the military

Brad: through my lens that’s correct [okay] As an African American who served in the military yes okay that’s exactly what I would say my experience my personal experience was like

Maia and did you run into was it a difference in opportunity for you or was it a difference in attitude of your fellow Americans are what what what was different

Brad: I would check all of those boxes. On one hand the military, we were almost encouraged to work with each other to form one team and, you know, accomplish one goal and individuals from all around the world and all throughout the country working in a small knit community we have to get along and work through our individual differences. We worked as a team of blue, if you will, in the Navy or we all were green as we would say of Marines.

Outside of the base it didn’t feel the same, it felt divided. that American dream that we all talk about and reach towards it felt a little, a little more out of reach once I stepped outside of the gate. I used to hear the stories that my, my grandfathers and uncles who also served in the military talked about with regards to racism and you know their experience and you know for some reason as an African-American is served I was almost too naïve to think that we had moved past that as well because of the work experience in the military and it being so diverse it be calling each individual that I worked with family you are my brother you are my sister you know despite where you were raised how you were raised. I learn about your story you learn about my story let’s work together move together that’s how I thought America work outside of the military as well. I was quickly smacked in the face with reality as far as that goes.

I moved to a town called Wilmington North Carolina the history was a little overwhelming but through learning and my own personal experience it open my eyes in through discovery and conversations with locals it allowed me to learn where I resided and I know I just felt different almost ostracized from from that dream that I was you know I signed up for

Maia: Yeah I ‘m… I’m a white person in a country that has a long stubborn history of white supremacy so I can’t really understand what you went through but I do know that if something like that had happened to me it would hurt my feelings to the– on an existential level it would… I would feel betrayed um… and, and that would be traumatizing, a very difficult thing to come back from because if you— first of all you don’t get this years back of believing, that feeling duped, “I just did this thing is a big thing I did” this her and then to connected to a know that everybody in this community no this that there are people of color who are serving their country in this way and to still have those attitudes in touring and that history be you know as best swept under the carpet and at worst celebrated, It must be horrifying for you it, it’s horrifying for me

Brad: Well what I would describe it as my my experience getting out was more of awakening that everyone is, going through right now as we speak. An eye-opening experience. It was a trial by fire personally with me, learning my worth as a black man in America. Despite service, like, I was black at the end of the of the day. I was still a black man and my service, it was almost rendered, you know, moot.

Which hurts. It sent me through a heavy depression. I went through a lot of drinking and a lot of different paths that I had to reach out to the ocean to rebalance myself each time with those personal struggles. At one point throughout all of that I eventually met Rhonda Harper who runs Inkwell Surf initially out of Santa Monica where she mentored inner-city kids, and allowed them touch tanks to learn about the ocean, and how to maintain their environment and also keep the ocean clean and also to surf and allow them to know that it’s a space for them to be as well.

Inkwell initially was a space where only African-Americans could go in California. Ronald was instrumental in having the area recognized with a plaque for Mr. Nick Gabaldon who was of African-American and Latino descent and he was a great surfer. He surfed with the best of them and he he lives on to this day throughout, throughout all of us with his story. And I carry that on and pass it on to the next generation that I work with here on the East Coast. Rhonda has been instrumental in teach me the ways of what she does and I have implemented with her direction a program on the East Coast to do the same thing. And it’s been magical. It’s been a journey. I’m a disabled veteran and I take the rest of my income and apply to the program. And slowly we’re gaining traction. Unfortunately, with the demise of George Floyd we all had to take a moment and reflect what’s going on in the world. And from kids to the elderly we’ve all had to, I don’t know, pay attention to what’s always been there in front of our face the elephant in the room, if you will. The racist elephant in the room if you will. And Rhonda recently organized the paddle out that you helped me organize locally.

Maia: This is how we found each other [correct]I’m so grateful for that solidarity answer

Brad: Correct. That was a magical moment for me— meeting individuals like yourself that made me leaving in humanity again. That showed me that people do care about compassion and, you know, that we stand together against this wave of injustice and are just going to get on the wave or wipe out, here we are, we’re all surfing together, riding together in solidarity. I still haven’t really reflected on that day, it was it was that big was too jittery to write a speech. It just kinda just came out of me in I’m told it was a great speech [It was incredible!].

I haven’t heard it but you know it was very moving to say the least don’t think I can really place words on the feeling that I experience. Everyone came together the traditional surfing way were we paddle out and pay respects to those who have passed. And for everybody collectively to come and paddle out and say that black lives matter… it, it brought me to tears. It took the breath out of me. There was a young man that I’ve known my whole military career that showed up that day— He took the air out of me. Because he’s seen my journey up until this point I still surf with him on the regular at my local spot at the Pipe at Carolina Beach. For him to show up that day as a married older man when I met him as a grom on Onslow Beach and, and show up at that paddle out it was very moving for me it’s

Maia: It says something about your life for sure that and at that moment and especially now since you are, you’ve really stepped up and stepped into this role as elder, as mentor to, to young people. To see the results of a relationship, to see somebody grow into a compassionate person who is willing to take a stand it’s gotta be hopeful.

Brad: It’s been it’s been a struggle in my head. We all struggle with personal choices in our lives and I chose to help people heal, despite my own struggles and, it’s just the way I’ve have always been. I’m a very compassionate person. When it’s time to stand up and fight for what’s right you’ll usually find me there, whether it’s through surfing or art our any other medium that I’m capable of doing. You’ll usually find me there.

Maia: Tell us a little bit about your life as an artist.

Brad: It’s kind of been there as a release for me— before surfing. Where I was able to escape to and kind of make my own world. I graduated from Cape fear community college with my associate in fine arts and right there after they hired me as a tutor to tutor the whole program— printmaking, art history, photography, the videography program— what have you. I was there for the next generation in line. And I met some amazing people in the art industry in Wilmington, North Carolina. Unfortunately, with my health in decline I haven’t been able to, to work with my art as much but I’ve been busy with Inkwell and other surf avenues so…

Maia: And you’re a dad…

Brad: That definitely keeps me busy. I am the father of a beautiful nine-year-old going on 20— Bethany Alden Turner. Her first name is derived from Bethany Hamilton the surfer. More so for her struggle and still being a professional surfer despite the struggles.

Maia: she too has overcome true adversity

Brad: I just tip my hat every time I watch a video of her surfing. Her surfing with one arm puts my surfing with two arms to shame any day.

Maia: Well that is true and you are also an amazing surfer. She is just somehow on another plane.

So you and I just met a little while ago and, and we met through this paddle out and I want to tell the story briefly because it was such an important moment for me. So, I am in, as everybody else is, this post George Floyd, Breanna Taylor, Ahmad Arbery moment looking for a way to do something I know not what. I just know that it can’t be about me and so I reached out to Rhonda after I saw that there was a Solidarity In Surf event in California. And said, “Okay I would love to have one of these here.” And she said “Well is Wilmington anywhere near Carolina Beach? “Why, yes it is.” And she said okay I will put you in touch with Brad Turner, and that’s how we found each other. And I have been so grateful, not just for that moment because it was really a turning point for me I would say in my entire really life as a surfer since those first questions came to me like where are all black surfers, why, where are they because literally maybe 1/100 maybe when I 200 surfers out there are not white never mind black.

Okay so so we meet at your Solidarity in Surf, which is incredible in such a beautiful, profound, moving moment, mostly white people– but one thing that I saw happened during that event was we’re in our circle on the beach the way these events work is you circle up on the beach you say some words you paddle out and circle up in the water splashing through flowers more words then you come back what I noticed happening as we were circling up listening to your incredibly moving speech were these two African-American families who came up and joined us and were so moved by what you were saying and I think by the whole scene there. And it really made me proud in a way to be a surfer that I have really not been. It many proud of our community surfers and I thought, “You know those kids just have suddenly gotten a different view of surfing than they ever could have gotten without you and that speech and that moment.” And it was so intensely beautiful and transformative for me

Brad: You know the family that you are speaking about I got to see that moment in photos and it’s pretty hard to look at them currently tearing up sorry about that at [no need to apologize] that was, was a powerful moment I can I can barely looked up at those photos because it was just a beautiful day and that, that very moment got captured and I don’t know if I can translate how it made me feel that day other than powerful and moving.

Maia: It was amazing and and and I— in no way do I mean to denigrate at all or minimize your service as a Navy corpsman but it made me realize that, I mean you’re still a very young elder. You are very youthful elder— it really put me in touch with the, the potential power of you to serve and I don’t, I don’t know if there are many people who can do what you did that day. I mean that, that seemed a unique especially in this environment— in this—

And we, you talked about Inkwell Beach which was an African-American beach in Southern California we had black beaches here [that is correct] as did many places especially in segregated states that really all over the country where it was de facto segregation is not legal segregation and those black beaches were, were crucial to African-Americans relationship to the water and just ability to decompress and reach this feeling that you have so eloquently described. And it was systematically and frequently violently remove. That access was removed. [Very much so] Mostly by white real estate developers and their allies who wanted that land for themselves [That would be the correct]. Freeman Beach [yes] yes is the name of the local beach which was owned by the Freeman family along with a lot of inland acreage as well [correct] and will link to this historian and some podcast interviews about it.

There’s a wonderful book called The Land Was Ours that you turned me onto and they’re a couple of podcast interviews with, with Dr. Kahrl the author.

But basically the disproportionate application of laws— one reading for, for the Freeman’s and another reading of the law for the white families. And the, the Army Corps of Engineers decisions to save white recreational fishing grounds after white fishermen complained and instead route this cut, which is not called Snows Cut, in a way that the environmental impact was all on the Freeman property.

Brad: That is correct.

Maia: And that kind of environmental racism has happened throughout our country’s history. The environmental movement writ large is dominated by white people who have worked to save their own playgrounds much as those white recreational fishermen did and in the act of saving “special places” in a lot of ways— and I’m not a historian, but a lot of ways in my opinion white environmentalists have at best ignored the disproportional impact of places that are very special to the people who live in them and love them and whose babies play in the dirt of them and the water of them. And it really feels like, post-Breonna Taylor, post-George Floyd, we have a moment in which leadership of these mainline environmental organizations is open in a way that they haven’t been before [I agree]. I hope that’s, that remains true you have what I think it’s just a tremendously beautiful vision. Would you please talk about your vision? Brad: Well, my vision for Inkwell and Black Girl Surf locally— I would like a safe space here in Wilmington, North Carolina— more specifically Carolina Beach that would be available for the youth to come and acquire mentorship, coaching, education— a space, much like I said, for release, a safe space, that’s their own, within reach to the ocean. Most of these kids that I plan to work with, and work with now are far from the beach and they live within the city’s reach.

Maia: Yeah, we’re were talking 10 miles which you for most of us who have cars and trucks is nothing but these kids have neither [correct]. And the busses where we live in Wilmington, North Carolina— there was at one point a streetcar line that ran from downtown to Wrightsville Beach. That’s why the street car was put in. The streetcar was taken out with many other streetcars in the 20th Century. The bus service the public bus service does pickup in downtown Wilmington but Wrightsville Beach, at this point, will not allow the buses to drop off in the town of Wrightsville Beach. This, to me, is a problem and that I hope at some point we can address. You hand I have been talking with an organization called Surfrider that is very focused on access to beaches, but you’re talking about the next level.

Brad: Correct, in my vision I would describe it as a surf STEM program with a little bit art included [Surf STEAM]. There you go that’s to summarize how I would describe the my vision for Inkwell Surf and Black Girl Surf to acquire a plot land and space where we can make those dreams come true, to have that opportunity to say “This space which at one time belonged to the African-American community, is now attainable to these kids.” And that’s a remarkable dream to think about and hopefully with the community’s help and Surfrider and a few other organizations we can make that happen.

Maia: I know from my own life that— you want to learn what you need to learn to survive always and once your survival is assured you want to learn what you need to learn to allow love to flourish. And people fall in love with the ocean… I mean they fall in love at the ocean— you got married on the beach very close to where you surf.

Brad: I did, my local break at Carolina beach— I got married right beside the Pipe there and I love it! It’s a very spiritual place for me every morning when I go paddle out with my friends I welcome everyone. Maia: I mean, your service is built around that love— You’re a healer this is what you’ve been doing your whole adult life and now you seem to be very clear on who you would like to help heal and how. And it strikes me as only good stewardship of our community resources that we, the collective we, of southeastern North Carolina put enough wind in your sails so that you can do the work that you seem to me predisposed, and uniquely able to do.

What would you say to, I mean, you are a responsible adult— you know how to maintain a disciplined existence, I could never make it in the military so my hat is off to you! What would you say to other sort of stressed, harried, overwhelmed grown-ups who don’t take time, or make time, or feel like they have time to get out into the more than human world, to get out into nature and be active. Make your best case for for why they should try

Brad: I think we live in a dettached world. We’re all intermingled and entangled into our electronics. I think we’ve taken our attention away from nature and, you know, a lot of pressure on everyone. We’re very stressed out people and I think will be very beneficial for everybody to take a look at the ocean, smell it, listen to it. If you’re brave enough, stick your toes in it. It will surprise you. There are some people who have a lot of fears about it but I believe in in learning about dangerous things that you deem fearful. You can go far. With knowledge there comes power. So, a healthy education about the ocean with would definitely be a first step, I would suggest. There’s a lot of learning to do but it comes with steps, or waves, if you if you will.

Maia: If you will. And you are married to a scientist right of the water quality experts I suspect you are all the time learning by osmosis [correct- LAUGH] in addition to your intentional study, which I know is that is also ongoing.

Maia: So, one of the driving assumptions and orienting beliefs around this Waves to Wisdom interview project is that as I entered the community of surfers I began to realize that surfing is much more than a sport and much more than a way to just get outside. It seemed to assume the role that religion or spiritual discipline assumes in the lives, not just of, you know, some devout people who go to church on Sunday, or go to Synagogue on Saturday or or pray a couple times, a week. But really much more along the lines of people whose full days are structured around this relationship to a higher power. It looked like surfers were, were very similar to you know, monks who had taken orders, or to devout Muslims who always know which way Mecca is, and are ready five times a day to make sure that they have in mind what their sacred power is asking of them. And it starting to feel like, for some people, not for everybody— some people are just out there for the rush, and they’re grumpy and not necessarily on a spiritual what we think of is a spiritual path but for some people this really helps them figure out meaning and purpose in joy and beauty and was a discipline. You think I’m on to something? Brad: Oh, definitely. I think we all feel the same vibration that’s in tune with the waves the ocean sends our way. And, it’s a therapeutic environment I dunno, it just draws you in, heals you without you even asking it to. I don’t know, it’s powerful. What can I say— it’s where I go and speak to my higher power. It’s where I go and release. I just feel it is beneficial for me to pass along to others as many as I can, old, young whatever dynamic you can throw in front of me. I just want to help people heal through water, through waves hopefully.

So wonderful!

Aside of that, I’d just love to crush of those stereotypical ideals that you know, black people don’t do this or that— fill in the blank. As a kid I heard a lot growing up in Georgia. To my surprise here we are doing everything from the moon literally to the bottom of the oceans, and the surface now— we surf, we swim. All the way in Africa around is in Senegal right now. Most people would say that you know those things swimming and surfing they are not attached to Africa but I would have to disagree.

I would almost say that, as a coastal people, they also had their own watermen’s story to tell…

Maia: Absolutely! And as a matter fact maybe one of the most famous surf movies of all time is Endless Summer. Plenty of people were not surfers saw that movie and one of the lies really untruths I don’t I don’t know that Bruce Brown did this on purpose he was probably just ignorant but they go to the West Coast of Africa and Bruce Brown, who’s narrating it, says this is the first time anyone’s ever seen surfing in Africa. And as a matter fact one of the first times that Europeans saw surfing, people riding boards recreationally in waves, was Cape Coast Castle, Ghana— long before [that’s correct] any white Americans had decided to surf. And we know for sure that people of color were surfing in Hawaii for centuries.

Brad: Right, and that very spot you’re speaking of, Ngor Island in Bruce Brown’s and Endless Summer that’s exactly where Rhonda is coaching local kids providing surfboards and lessons right there as Ngor Island at the local break making a change for the male and female population providing an education and mentorship right at that very spot but yeah in the video you can see Bruce Brown and the like surfing right there at the break and the local kids looking very tribal and cheering them on. you’ll now discover in that same spot that we surf too. Um, there is a hunger and a drive in the African and African-American, and each diaspora to surf. When we’re close to the ocean. It’s a beautiful moment to, to lay eyes on. You know, I started surfing very young and learning about the dynamics and the history and I am finding out much like my own Black history that there are gaps in surfing history that need to be told. and seeing it in Senegal right now is just beautiful. There are little groms with broken surfboards with the biggest smiles taking off on taking off on waves, you know, right there outside of their door. That’s something that you wouldn’t think would be tangible here in the US. As a matter of fact, I can’t really think of a place where that’s a thing here in the US where kids can go out the door, maybe a few yards from the beach and say this is my local spot.

Maia: Certainly not black kids. Plenty of little white kids.

Brad: Oh yeah, that’s the standard, I would say.

Maia: And we will link to some, some really powerful histories of how we got into this situation. And we actually live at the very northern tip of an historically African cultural community called the Gullah Geechee

down to Jacksonville, Florida— the southern tip of it. And until the transition of ownership around real estate values— waterfront real estate values started, there were really, especially on the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia, a lot of African culture endured. And so many of the things that we think of as Southern, like Shrimp and Grits, are really African!

Brad: Oh yeah!

Maia: And I don’t think a lot of people are talking about that. And I think it’s time we started.

Brad: Definitely! Maia: OK, good. Is there anything else that you would like to talk about? Brad: Just like to let everybody know that, you know, as far as the surfing community goes, Inkwell Surf, Black Girl Surf, and many other organizations— we’re out here and we’re trying to make a difference in the community through surfing. Through surf therapy, through competition, through mentorship. And I think with this new wave of change we can all come together and make some things happen in the surf community to make it right. Make everybody feel like they belong at the beach and everybody feel comfortable. I can always use a hand. You can check out Inkwell Surf and Black Girl Surf and I would very much like for everyone to donate wherever they can— financially, with a surfboard, a wetsuit, your personal time volunteering. I’m a disabled vet so a helping hand would definitely be appreciated in any aspect and we’re looking for the whole community to come together and make a beneficial change for the surf community and hopefully let these kids know that, you know, they have a place on the beach just like everyone else. Hopefully, I can be beneficial to that happening.

Maia: Or instrumental.

Brad: Or instrumental. Thank you

Maia: Yes! We will make sure that it’s easy for everybody to find you and find your cause. And we’re still at the very beginning of figuring that out- figuring out ways to support you. So if anybody out there has any expertise, [yes, please] you know, fundraising or project management or any of that sort of thing we are wide open to your input.

Brad: Yes, very much so!

Maia: And I can hardly wait until the next time we surf again!

Brad: Oh, thank you!

Maia: Thank you! So much for your time in doing this—it’s been, as usual, a thorough pleasure.

Brad: It’s been a blessing, thank you.

Maia: And we’ll see you in the lineup very soon!

Brad: Oh, for sure and hopefully there’s another dolphin.

Maia: Oh my gosh, tell the story about the dolphin!

Brad: LAUGH

Maia: Do! Tell that story!

Brad: So, the day before yesterday we were all having a session out at the pipe and right in front of you pops up a beautiful, beautiful dolphin. You kind of have to make one of those split-second decisions as a surfer. To decide whether it’s a shark or a dolphin and it was a dolphin, so close that you could touch it.

Maia: I was amazing!

Brad: They often show up there and it’s always magical.

Maia: It blew out of its blowhole and I got spray on me! It was incredible! I felt like I was Baptized! It was to powerful and wonderful!

Brad: That’s how we do it at The Pipe!

Maia: Oh my goodness! Holy cow- yeah, I want that to happen every time!

Brad: Only way to make it happen is to show up and surf…

Maia: Keep showing up! I intend to do exactly that, Sir! Thank you so much for your time I am so grateful!

Brad: Thank you!

Maia: I want to end this interview with a few words about whiteness, my whiteness. When Brad talks about learning about what we deem fearful, he could be describing my own heart when it came to developing deeper understandings of the ways whiteness has played out in my life, what I’ve seen and, perhaps more important, what I’ve easily ignored.

Now, I hold a deep hope that these interviews offer something substantial to all humans, but right now, I have a few words for those of us who, to loosely quote James Baldwin and Ta’ Nahesi Coats, those of us who “believe we are white.” Unconfronted, the lie of “whiteness,” can make the expanse of what we don’t know, the territory of our own ignorance, oceanic in its scale.

Dipping your toes in the water of the knowledge that might reveal that ignorance might mean letting go of some long-held patterns and assumptions— It can seem terrifying but once you get those toes wet and wade out into the water, a lot like surfing, you can learn to value the tumbles and tossing you’ll get as you learn new ways of seeing. I began to relish every wipeout as I watch my ignorance evaporate, bit by bit.

Have I lost you? What does whiteness have to do with surfing? In its modern construction, especially in the popular imagination, ideas of whiteness are foundational to our understanding of what it means to live a coastal lifestyle. These dynamics continue to play themselves out on beaches all over the U.S. and all over the world even as people of color reclaim or claim anew the pastime, riding boards on ocean waves, that the ancestors of Hawaiians and West Africans and other people of color invented— and that some of them never let go of.

So when we, when I, went to the waves and felt afraid that the locals might make me feel unwelcome, because I was a stranger, because I was a woman, because I didn’t know how to surf, because I was old, or because I don’t look straight, or because of a million things I was scared of, either real or imagined, one thing I never had to worry about was the next level of vitriol that I might face if my skin were darker. I never had to contend with 400 years of systems that worked against my family building the wealth and a culture of access that allowed me to have the leisure and resources to get to the waves and be right! And in the process find so much more than surfing.

I never had to contend with a history that worked even more insidiously after segregation became illegal. As the poet Ross Gay says after the “Brown v. Board of Education…” Supreme Court decision, the U.S., north and south, ‘[inaugurated] an era of great racist innovation.” Increased entry fees at public pools where kids might learn to swim, increased parking fees, decreased public transportation, and a million other apparently race-blind decisions, had deeply disparate racial impacts.

None of this learning I’m inviting you to engage in means we, not you and not I, have to disregard or disconnect from the hurts we’ve suffered. It’s not about that. It’s about making time and space to learn our history and see who isn’t here with us and why. It’s about opening up to the truth of who we have been, of who we were taught to be without thinking, and in the process, opening up to, regardless of who and what we personally intended, the truth of who we are. It’s the kind of truth that must precede not just reconciliation, but healthy relationships– between humans, yes, but also our relationships with ourselves and with the more than human world.

Something comes in the place of these old patterns, once we start to dismantle them. What came for me was an unending gift I’m still, after years of wonder and discovery, just seeing the outlines of, like a massive headland emerging from the fog— it’s one that has a thousand promising and abundant paths for further adventures.

Now this one path, the one I began alone, the one that allowed me to find Brad at the Pipe during Solidarity in Surf— it made space for us to collaborate on a plan, to work with a local, predominantly white organization that hasn’t focused on barriers people of color. We drafted a proposal for a new volunteer position with the Cape Fear Chapter of the Surfrider Foundation. I’ll put a copy of the proposal on the website for you to use as you see fit. Our collaboration is just at its beginning and it’s already been a profound gift to me.

The capacity of water to dissolve artificial barriers, not just between ourselves and others but between our deepest, most wounded selves and the healing we need, in whatever way we most need to heal, has been unparalleled in my life. So has dealing honestly with the way I was able to access that relationship with the ocean just because I decided to and, more important, dealing with the fact that it occurred to me in the in the first place to seek healing in the ocean and looking squarely at the ways that ease of access might be one aspect of whiteness, well has led to some of the most difficult, rewarding, utterly beautiful rides of my life.

I invite you white-bodied surfers to join me on this heart expanding journey of connection and healing. There will be links to the YouTube channel, to Inkwell and Black Girl Surf, and to many other resources on the Waves to Wisdom website, with this interview. I heartily, really, with my whole heart, encourage other surfers who believe they are white to ride some of these challenging waves too. I promise, Brad is right. With knowledge comes power.

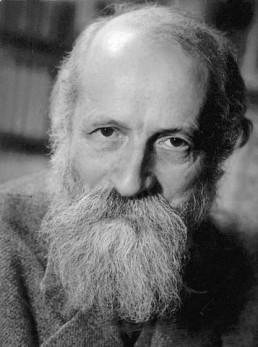

Interview: Dr. Antonio Puente

To listen to the interview, scroll to the Player at the bottom of the page.

" ...it was a very difficult time but then you know it's when things are falling apart is when you really get a chance to make things happen so as I tell somebody when I took over the position, I'm tenured, I got my citizenship and I don't give a shit."

~Dr. Antonio Puente

Transcript

Tony: it was a very difficult time but then you know it’s when things are falling apart is when you really get a chance to make things happen so as I tell somebody when I took over the position, I’m tenured, I got my citizenship and I don’t give a shit.

Maia: I’m Maia Dery

How do you feel when somebody or something with much more power than you have, knocks you down? Or tells you or maybe even shows you aren’t good enough?

What do you do about it?

Get back up?

Struggle to not believe the naysayer? Or ignore the knock-down?

Try to learn something so you can come back with more capacity and strength?

When I recorded this interview with Dr. Antonio Puente, who, among other things, is an avid surfer and celebrated neuropsychologist, we couldn’t know how much this pandemic would knock us all down. But I suspect that, had we known about the coming challenges, the interview wouldn’t not have been much different.

Surfing and all ocean play, after all, are practices of scanning, of seeking, of developing relationship with something powerful over which you have absolutely no control and, at least for the first umpteen years, of getting knocked down over and over again. The kind of play is also a way to connect, with yourself, with the more than human world, and with other humans. Whether you love waves or weaving, hiking or haiku writing, some kind of passionate, disciplined engagement in an endeavor that allows your body to come into nuanced collaboration with the wider world is, I believe, one of the most rewarding ways to inhabit your time. In Dr. Puente’s case, it seems to have helped him overcome some long odds and some powerful forces that might have kept him from becoming who he is now. In addition to being an inspiring surfing story this tale of an immigrant boy overcoming long odds is, I think, also a great American story.

This episode is dedicated, with love and so much aloha, to the memory of Tiko Losano.

Welcome to Waves to Wisdom

Antonio: I’m Antonio Puente, or Tony as some people call me. I started surfing I believe in 1964, in Jacksonville Beach, Florida. It’s been quite some time.

Maia: So, you were just little boy.

Antonio: Yep, on a wooden, woody surfboard. It looked more like a battleship than a surfboard. As you paddled out the waves actually broke for you.

..this is not, you know, as you catch the wave, as you paddle out, as you paddle out the waves would part for you.

Maia: You had a little Moses effect on them. Would you just talk a little bit about where we’re sitting right now? Antonio: Sure, this is a club called The Surf Club. It’s towards the north end of Wrightsville Beach and it’s a beautiful, small pavilion overlooking the ocean. And we’re very fortunate to be away from the wind but in front of the view.

Maia: And the sun has just come up above the water’s edge and it is a gorgeous morning here! Okay, I would love to start by talking a little bit about your childhood.

Antonio: Well, I was born and raised in Cuba. I was privileged. One side of my family was involved with rum. The other side of the family was involved with legal affairs. In fact, my maternal grandfather was head of the legal department at Bacardi. So we were well to do. Had my own nanny and a chauffeur at that. And then after Castro took over we came to the United States on November 6, 1960 with $300 and a change of clothes and no knowledge of what we were getting into. We assumed a good revolution in Latin America would only last a little while and we would return… well, that was 1960.

Maia: It was a while ago.

Antonio: It was a while ago.

Maia: Do you have any memories of Cuba from your childhood? Antonio: Yes, I do. I not only have memories but they’re reinforced on regular occasion by the family and especially my Mom and Dad talking about Cuba. And then subsequently I returned to Cuba, first almost 40 years later in 1999. And have returned pretty regularly since then. So, I left as a refugee and I come back as a decorated psychologist.

Maia: How about that! And did you and your family speak English when you came here with $300? Antonio: No, my mom did. She had gone to boarding school, high school in Philadelphia but my dad and my brother and I didn’t know. In fact I remember it being explained to me that “I know this is maybe odd for me to tell you, Son but they don’t speak Spanish here.” I said, What am I gonna do?” And she said “Ah, you’ll figure it out.”

Maia: Oh my goodness! How old were you then? Antonio: I was almost 9 years old [almost 9]— nine years old in North Miami Beach. We lived in a 1-bedroom apartment with two families, my brother and I were very fortunate, we had the kitchen floor to sleep on. [Wow] So we were the only ones who had a private room.

Maia: Wow, okay incredible— so you went right into an English speaking school system then I imagine? Antonio: Right.

Maia: So then you were surfing the whole time then, in Miami?

Antonio: No, in Miami I didn’t get a chance to go to the beach very often. We were just trying to figure out how to get food and learn the language. We subsequently moved to San Antonio, Texas when I really first came in contact with what I guess we call discrimination. I realized at that point even though I was a child, despite the fact we didn’t have food, and then at one point, we didn’t have housing as well, that there was very active discrimination and there was a pecking order, at least in the United States in Texas at that time. There were the white people and then there were the black peopled then there were the brown people. So considering that we were really out for the count and we were being discriminated against, it seemed to my mom and dad that, if we were going to suffer, under those circumstances, we might as well be among other people that were similarly like-minded.

So we returned to Florida where my family settled in Jacksonville, Florida

Maia: And there are waves— as opposed to San Antonio and even Miami there are consistent waves in Jacksonville.

Antonio: And that’s where I first came in contact with waves because one of my father’s friends Cezar Garcia, had a son that— who knows exactly how, he had been exposed to surfing and he was always willing to give me a ride to the beach. From 1964-65 on I went to the beach with him as often as he would and I’ve continued surfing ever, ever since then.

Maia: And you ultimately decided that you interested in psychology and went to graduate school and…

Antonio: Yeah as far psychology, I was really curious about how people came to understand and engage and successfully adapt to the world and it seemed to me that psychology was as good a discipline as any that that provided a vehicle to address those issues. It came to me in my first psychology course in a small community college in Jacksonville, Florida. It actually was a segregated grammar school that had just been given over to this fledging concept which was junior college in those days. So, I went there then subsequently the University of Florida where I was able to continue surfing and subsequently to, to pursue the career at the University of Georgia where there were no waves but on to graduate school and psychology as a formal career path.

Maia: What, what a fascinating motivation that the curiosity about how people adapt to the world. So, we’ve surfed together a few times at this point in Wrightsville Beach where it’s a home break for both of us, including it really spectacular surf morning a couple of couple of days ago.

Antonio: It was the vibe of Wrightsville Beach, aloha spirit all over the place with wonderful little waves.

Maia: It really was. So many people, it was very crowded, it was it was the kind of day when I normally would not have gone where we went, but because I was with you I did and I was so grateful because I was surrounded by people but they were the best people.

Antonio: We’re very fortunate.

Maia: It was wonderful, it was like being in a welcoming friend’s home, it was really fantastic. Okay so you went to graduate school and you told me a story previously that I hope you’ll tell again about wanting to put together what were then, speaking of segregation, two really separate areas of psychological inquiry.

Antonio: At that point I was curious about this issue of adaptability, understanding the world and moving forward and it seemed to me that studying abnormal behavior was really successful because some people would make it and others wouldn’t but the mechanism that would mediate the entire process to me seemed to be the brain. And unfortunately at the University of Georgia then, even now, the individuals that study abnormal behavior were the clinical psychologists, they were on the first floor. The people who study the brain were primarily studying animals and normal behavior, like learning, and they were on the sixth floor.

I wanted to bridge the gap between those two… I did so by getting a Masters in, what was it January 6, 1978 and then I defended my dissertation January 13th, 1978 so I did them pretty much in parallel fashion rather interactive which is what I was hoping to achieve.

Maia: One of the things that I have noticed since learning how to surf breakfast yeah one of the things that I’ve noticed since learning how to surf is, it looks to me as though, certainly from my own experience and from observing others, that many surfers, not all, but many tend to have the capacity to see past artificial barriers that we erect. And I spent 17 years in an academic world and there is really nobody like academics to construct some really impenetrable barriers, especially between disciplines. I wonder if your habit of surfing and all of this fluidity and these distant horizons might have helped you understand that these two things are not actually separate? Tony: Well, let’s go back to your comment, you said regarding academics, having been in academia formally since I was the age of 18 and continuing as a Professor of Psychology at the University in Wilmington, I can’t tell you how surprised I am, even after all these years, the unbelievable politics associated with academia. People fight so aggressively over so little to accomplish even less than that. It is beyond surprising.

You kind of wonder— there are certain places that life should be pure and the pursuit of knowledge and dissemination of that information seems to me that would be an obvious place were peacefulness, truth, collaboration, and collegiality should be present to try and move the big agenda of our world forward. I have to tell you it is still a surprise to me that that has not occurred. But that has been the place where I chose to pursue a career largely because of the opportunities that academia does have. For example, access to young people, access to thinking what you want, when you want. As long as you produce then maybe you’re in a position to do that, but academe has been the foundation for where I was able to pursue that.

Now at same time it seemed like a fulcrum needed to be established so I could handle that. Because, whereas I was very interested in the pursuit of knowledge and dissemination of what I knew, as well as having access to young people, and fresh ideas, etc. I also felt that that aggressive attitude that seemed to be so contraindicated in the pursuit and discovery, of knowledge— that I needed something that would help balance that. And for me that was living at the beach so I could somehow or other manage that, that difficulty which was present, ever since I came to the US, in many ways. And has continued even to this day. A place where I could disappear, at least emotionally and mentally, that would help ground and establish a place to, to provide a balance that can only be achieved if a fulcrum had been set up— on one side the motivation for the pursuit of information, knowledge, discovery, on the other side a sense of well-being and, as you sometimes say, wisdom, that really is hard to find anywhere else except when you come in regular contact with lots of water.

Maia: Yeah, we talked a little bit about this but there is a loose association of researchers and an idea called “Blue Mind.” People are studying something that many of us know intuitively that being around the water feels good and you go from the water back to whatever world you live in on dry land rejuvenated, relaxed, and potentially more creative and effective than you would’ve been if you had not.

Tony: Yes, I’m familiar with Blue Mind and actually we use it at the American Psychological Association, at least one branch of it. Yeah, to me, some how or the other I don’t know the science of it but I know the life of it. So it’s been part of who I am for that matter, my immediate, and my extended family.

Maia: Alright, well that observation is really interesting to me because you’re in a position to understand how the brain is actually responding to this stimulus much better than I am. You wrote a paper in which you were talking about the traditional mind-body split we have in Western culture and the ways that psychologists have approached behavior and brain over the history of the profession and you came up with the phrase “reverse epiphenominalism,” which is so interesting to me. My understanding if that is that it’s not just our brain that dictates behavior but that what we do in the world and the ways we think in turn create the ways that our brains act. Is that part of what was in the paper? Tony: Pretty much. It was my way of trying to get some understanding of how is it that we end up producing who we are. It really is an idea that emerges from the work of my intellectual mentor Roger Sperry who discovered the two sides of the brain. His concept was pretty straightforward, and that is that neural structures of the brain give rise to a mind or consciousness and in a sort of epiphenomena, upward causation and then the consciousness in turn dictates how the neural structures underneath end up functioning. And that’s sort of downward causation. So it’s a reverse epiphenomena because we think of epiphenomena as an outgrowth of something but this is the outgrowth of the outgrowth. So, it’s a unified system of function.

Maia: Interesting, okay so if someone, for example, like you had a multi-decade habit of, of going to the water as a way to make sense of, recover from, regenerate for life— especially that they sort of intensely intellectual world that you live in to have this embodied practice, it could potentially change the way your brain was structured and functioned. Is that correct? Antonio: I don’t know, certainly could be, I don’t, I don’t again I don’t know the science, I don’t do the science of surfing at all but I certainly do the lifestyle pf surfing and I think it’s been endemic and core to who I am and maybe has allowed me to maybe to engage life in a more successful fashion than I would’ve done otherwise.

I always wonder, for example, if I had been given the opportunity, which I was it and seized it, to go to New York University where I would work tons of hours a week and be exposed to asphalt rather than water, what would’ve happened. I wonder whether I would have ended up in the same place, unlikely. And I wonder if I would’ve been as successful, unlikely, and maybe as comfortable with life, most unlikely.

Maia: Really interesting. So, let me just, for anybody who doesn’t understand the significance of what you said, you were essentially offered what in your professional world would’ve been an extremely high-status job at one of the premier tier 1 research institutions in the country and you decided that it was more important to be someplace where you can access this lifestyle?

Antonio: Well I thought the lifestyle was really important to both raise a family and have a personal life but have a balance with my professional life and I… whereas I think being in a top-tier university may have been very useful in my career and probably in anybody’s career at the very beginning, there comes a time in a career where the institution stops caring a person and that person starts carrying the institution. And that lifestyle becomes really critical. I’ve never been one of the opinion that you should ignore your personal life as you pursue your professional one. In fact, I thought that having both successful would be very good. I often tell my kids it’s not that hard to be a successful academic but it might be not as hard to have personal life that’s also gratifying but it’s insanely difficult to do both and when you do both you and end up having great results.

Maia: Present company a testimony to that fact! Fantastic, so, my understanding is that you recently spoke at a commencement ceremony?

Antonio: Oh, yes that was, that was really surrealistic. I spoke the Department of Psychology commencement ceremony in Athens, Georgia. It was really pretty gratifying. It was a great audience, several hundred students graduating but was what was really unique— it was actually two things were unique. The chairman of the department was the mentor of my oldest son who graduated from the University of Georgia as I did. But also when I was a student there in 1974-75. Specifically, I recall being told that I didn’t know enough English to be able to succeed as a psychologist. And I was encouraged to to leave the University and possibly psychology. So I took a, a few weeks off, went surfing, to be honest, worked at a psychiatric hospital, the 11-7 shift. I couldn’t tell difference between the residents and me at that particular juncture of my life. But did that, surfed in the morning, and came to the conclusion that they were wrong and returned and off to the races I went.

Maia: Oh, my goodness, that gives me chills that the waves told you that or that you were able to hear that from yourself in those waves.

Antonio: Yeah, they were important in trying to reestablish that balance I had lost by spending nine months not being very successful. So it was really great to return. I’d been there as a student, an unsuccessful one and I was there as a parent cause two of my kids ended up going there. But this time I came back as a celebrated, distinguished alumni. When they invited me I said “Are you sure? Forty some years ago you guys were asking me to leave the program and now you’re you asking me to speak at your commencement. Their response was “That was then, this is now.”

Maia: It’s a different world in some ways, that’s quite something. And, and one of your, one of your many roles in addition to being a professor at UNC W and an avid surfer is you’re head of a branch of the American Psychological Association. Would you tell us a little bit about that? Antonio: Sure. I’ve been involved with organized psychology for many years in one role or another and I particularly was interested in making sure that psychology had a seat at the table rather than a line on the menu and the goal was basically to get this way of thinking more active in our society and, uh I decided to become or run for the position of president which after a couple tries I was unusual opportunity to you become that as 125th president 2017. That was a particularly tough period for our society, also for our country. I inherited an association that was essentially broke and fragmented largely because of the assault on such things as science and the importance of person and diversity in our society, largely because of the current administration. And it was a very difficult time but then you know it’s when things are falling apart is when you really get a chance to make things happen. So as I tell somebody when I took over the position, I’m tenured, I got my citizenship and I don’t give a shit. So, let’s make things happen.

You know. I left my country, left everything so no reason to be cautious during times of crisis. So we were able to turn the ship around and in the process we realized that we do not have infrastructure to do advocacy which is so important in our society. Somebody has to carry the flag of discovery, the flag of truth, and of diversity, and of decency. We didn’t seem to have that in any way, shape, or form. So we started a new association that is part of of APA and I took that over when it started earlier this year. So I finished my tenure as president, and took over in this particular capacity at the present time.

Maia: Excellent and so now you, having engineered the organization so that it can support advocacy, you are actively engaged in doing that.

Antonio: That’s right. We now have an infrastructure. We have 20 attorneys, a director of advocacy. 60% of the basic budget, the membership fees, excuse me, that comes into this association gets directed to this activity. So we now have an economic revenue source and we’re developing the agendas as we move forward with the basic foundation that if, if it has to do with human behavior and has to do with science then we’re there to provide direction and as much as possible advocacy.

Maia: Okay well to bring us to a level that people can understand what you mean when you say advocacy, what would be an issue that right now and 2019 your branch of the organization is actively engaged in trying to address?

Antonio: Well I’ll give you one very specific one and one that applies to me as well. For a long period of time back I did not have appropriate papers, I was an undocumented individual. In fact, in fact, in 1978 I entered the country from Grenada, West Indies, not realizing I was undocumented and had been undocumented for 10 years. So I’m one of those undocumented people we talked about. And also, as you know, the president of the Association and so, so involved in our society today. So, so we held hearings in Congress and now we’re trying to develop bipartisan support to make sure that we don’t separate children from their parents and that we come up with a reasonable approach to border security. I am not against border security but I am against dehumanizing people and causing trauma. In some ways what we’re doing to these children and these families will cost the United States a lot of money, a lot of pain, and more importantly, loss of direction of who we are a country.

Maia: Here, here. Yes!

It’s really quite a story for the ages and for this age in particular. You’re a living example of how somebody can come in with no skills relevant to the workforce, being a child who had no English, and wind up really changing our country for the better on a very high level.

Antonio: Well, whereas I appreciate on the surface the idea of, you know, let’s populate certain skill sets that we need, for example, computer programmers or coders and so forth, the idea that we are no longer going to value family as a way to populate the immigration system shows a lack of, of empathy, understanding of how human nature works. And also, also this is really important, we were founded on an open attitude about people.

Maia: Yeah, one aspect of your work that I think is particularly interesting is your legal work. Would you talk about that a little bit? Antonio: Sure. When I started this work on cultural neuropsychology the idea was to understand the role of culture and how is it playing in brain mediation of discovery and adapting and in the process it became more pragmatic in terms of trying to figure out what tests could be used to were measuring the construct in question. For example, intelligence, rather than some variable that was extraneous, such as time. So the, the idea became develop tests that were true to the concept rather than the measure of a variety of things that provided all kinds of problems and errors in our understanding of the client or the patient.

And in doing so, I started getting more focused on developing appropriate test for Spanish speakers which is a large population United States and a huge population of the rest of the world. There are very few neuropsychologists in general almost none who speak Spanish, about 50 of us in the United States.

And unbeknownst to me, some of this became interesting to the legal field. Specifically, individuals involved in the death penalty. Because it turns out an increasingly large percentage of individuals on death row are Spanish speakers and for what it’s worth it turns out that Hispanics are sentenced to die four times more frequently than Caucasians and for African-Americans is three times. So, a disproportionately large number of them were being sentenced to die and the question was, are we simply not understanding these individuals? So, I started being called upon first, interestingly, in a local county and then subsequently throughout the US. In fact, I have a case coming up next week in New York. The goal is to go discover what’s going on with this individual and make a reasoned estimate of whether their brain is affected.

So, along those lines I have been working on doing neuropsychological assessments of Spanish speakers that have been sentenced to die— I don’t know for sure I think I’ve done between 100-150 these cases throughout the US. It continues being a significant part of my work I see more patients who are clinical, if you will but the bulk of my time seems to be in these death penalty cases, that they take hours and hours and hours. I just finished a case and worked on for approximately 10 years, several hundred hours. I interviewed the family tested the went to their hometown, Mexico. When you, when you get to that level analysis not only do you know the brain, but you know this person probably be better than they know themselves. And the goal is to provide information to the court so they make a good decision, make sure that we’re not sending to do someone just because of their culture or other misinterpretations. The goal is to provide good data, as best scientific information as you can at that particular instance so the issues are just entirely legal rather than anything else.

Maia: Fascinating— yeah, seems so important because many of the people who are making decisions in court, the judges or the attorneys who are structuring the argument may not have the cultural competency to put the context to it…

Antonio: Could well be! I’ll give you an example. In Harris County, which is basically the county seat of Houston, Texas sentences to die more people in that county alone per year than the entire world combined. [Wow] There can’t be that many [unbelievable]. So, there’s something awry and my job is to bring an understanding to a very complicated situation. Justice obviously goes both ways— for that person who has been victimized as well as the person who is being sentenced. But either way the goal is to erode error and increase accuracy.

Maia: Wow, such important such important work. Okay, just to put this in a nice little package. You have a very busy academic post at the University of North Carolina in Wilmington, you have graduate students, undergraduates, departmental responsibilities, you’re director of a branch of the American Psychological Association, you have this active practice as a legal expert providing this kind of crucial context in capital, mostly capital cases. You overcame a language barrier and economic hardships to achieve all this professional success. What do you think has been your greatest success? Antonio: Well, for me the greatest success, in general, has been raise— raising three very normal children, all who surf. LAUGH All decent human beings that contribute to society.

But maybe one of my greatest successes, at least this question was asked me when I was president, “What’s been your greatest success as president of APA?” I’m sure there’s something more tangible than I can provide than what I’m doing now, but probably one of the greatest things that came to my mind immediately was that I surfed in three different continents in one week as president of the US (sic). I surfed in Europe, and I surfed here in the states and then I surfed in South America. It seems to me that if I consider that to be a crowning achievement of my year as 125th president of United States, excuse me, of not of the US but of the American Psychological Association [wouldn’t that be wonderful if you were!]. LAUGH Oh that was a Fruedian slip! But if I could be president of the society and that was my greatest accomplishment one could argue that maybe I have my head in the right place.

Maia: I would absolutely argue that, yes! So it’s, it’s a very busy job, has you traveling all over the place and some of those places you are able to get in the water…

Antonio: If I have the opportunity, if it’s close to the water, I’ll make an effort to make that happen, which is always extremely gratifying and to my hosts extremely surprising.

Maia: You are a distinguished character and so to don a wetsuit or some board shorts and take a big board out in the water and you are a shredder, you know, to really catch and ride, gracefully, some big waves— I’m sure it gives them pause.

Antonio: Well, I’m not sure I’m a shredder, I’m probably closer to a kook but either way it’s a pause for those people who are not familiar with this lifestyle.

Maia: Do your children surf? Antonio: Yes, all my children surf and my wife, in her day, used to boogie board as well. So, in fact, all of them grew up literally a few feet from where we’re having this discussion. We bought an old house here at Wrightsville Beach and didn’t have enough money to establish a heating and air conditioning system but we did have a small tent that we would pitch up, or at least my wife would, every day and the kids would just spend their days on the beach. So they all grew up right here. And as soon as they could, put a little life vest on ‘em and then boogie board, after that a board. They all still do it.

Maia: So this practice has really been central to your personal life for your entire adulthood?

Antonio: Yeah, and for my kids [and for children] yeah, as a matter fact we try to take a family vacation every year and we’re going to do so, this year all of us. To where I took my wife on a honeymoon and I told her we’re going to some of outer island in the Bahamas. She goes, “What’s there?” I said “I think there’re waves.” And we’re going back to celebrate the beginning of our married life which started with riding waves in the middle of nowhere in the outer Bahamas.”

Maia: So wonderful! And how many years have you been married now? Antonio: I think 100…

Maia: One hundred years, ok good

Antonio: We were married in 1977.

Maia: Okay, beautiful and your children are grown now? Antonio: Yep. My daughter’s a psychologist in Melbourne Florida and she and the kids live the beach life. My other son, my oldest son, Nicky’s a neuropsychologist at George Washington University and he still surfs as well. And then Lucas, my youngest son, is married and has a kid and lives in Northern California and surfs from Santa Cruz to right below the Golden Gate Bridge, which is Fort Point which I always worry about because between him and the open ocean and lots of current is not much.

Maia: Right! Yeah that is a… it’s a dynamic ocean environment there. But talk about a selection of waves, wow!

Antonio: He gets the better waves of all of us.