Brown makes a case for the benefits of disrupting American culture’s frequent, knee-jerk suspicion of anyone whose life seems especially playful, of dismissing anyone who appears to be having too much fun.

We are evolutionarily engineered to need life-long play in order for our brains to continue to grow and develop in the ways that keep us happy and healthy.

Brown says “the opposite of play isn’t work.” It’s depression.

Interested in how you can make your life and brain better (and have fun in the process)?

After studying more than 6,000 humans, Dr. Stuart Brown has a simple answer to enhancing your life and time right where you’re living them— whoever you are, whatever you do––, play more. In Play: How It Shapes the Brain, Opens the Imagination, and Invigorates the Soul Brown explains some of the contemporary research that points in the direction of increased playfulness as the pathway out of a range of challenges more diverse than those that bring people to Nosara. According to Brown, there isn’t much we should take more seriously than our fundamental, biological need for internally motivated, unstructured play. It’s a need that powerful cultural currents pull us away from honoring. Brown’s book is a call to action, asking us to, please, for your own sake, be counter-cultural. And beyond the level of basic self care, play is a route to flourishing and enhancing your mental and physical health, creativity, and cognitive functioning. More creative, healthier, smarter people sounds like a recipe for positive societal change, not just self improvement.

So what is play?

According to Brown, play, while difficult to define absolutely is not a subset of activities but a state of mind.

If you’re playing:

You feel what you are doing is voluntary

You’re undertaking an activity for its own sake because it’s inherently attractive, not because it’s useful

You have diminished consciousness of self

You feel the activity has improvisational potential

You want to keep doing whatever is making you feel so darn playful

You experience freedom from time

In that last characteristic of play (which is also definitional to the concept of flow) I’m reasonably certain Brown means the chronos kind of time. He wants you to take inventory— when was the last time you lost yourself in the unbridled joy of deep play? If it’s been too long for you and, especially, for your children, you’re courting trouble. Brown’s extensive research includes studying a range of folks, from the happiest and most successful (Nobel laureates) to the violent and sociopathic, (mass murderers). Brown’s take on the sociopaths? Not surprisingly, most of them had a history of abuse but he also found a crucial absence from the histories of the most violent males. No matter who they were or where they were from, they didn’t play enough.

Brown makes a case for the benefits of disrupting American culture’s frequent, knee-jerk suspicion of anyone whose life seems especially playful, of dismissing anyone who appears to be having too much fun. Adults who play a lot risk being perceived as wasting time in unproductive, frivolous, probably selfish undertakings. I’ve witnessed (and suffered from) this cultural tendency plenty! As someone whose vocational life and professional calling has often looked like the sort of “useless” activities most people do as amateurs, for fun and love, I’ve winced under the disapproval (perceived or real) of other adults as I pursued photography, backcountry exploration, and surfing as if they were my job until, at last and somehow, each, in turn, actually was part of my job. Now, looking from the vantage point of middle age, I know that if my play impulse hadn’t been so undeniable, I would have bowed to pressure. If I’d had any real choice I would have spared myself the shame and angst of not fitting in and chosen something more grown-up, more lucrative, a more appropriate use of my time.

As I read Play, I’ve never felt more grateful for the lack of impulse control that kept me outdoors, learning, moving, and trying to get others to come along for the rides. To have bent to the pressure to achieve something that looked more normal and serious and important, to have denied these fundamental enthusiasms, to have used instead of living my time, that would have been an egregious denial of something at least approximating the sacred. It would have meant rejecting the most abundant gift I’ve received in life— an occasional, often unpredictable, always fragile opportunity to help other people connect or reconnect with the meaning, joy and potentially playful depth of life that’s on offer to most of us, regardless of adversity, each day we are fortunate enough to be breathing as the sun moves across the sky.

Brown notes that while the state of being he labels play requires engagement in a “useless” activity, play itself is not only useful but primally so. The very uselessness of the activity itself must mean that the state of mind is somehow crucial for us mammals, or it would have been weeded out by evolution long ago. He introduces husband-wife research team Johanna and Robert Fagan who studied play in grizzly bears. The Fagans found that the individuals who played the most were the most effective at surviving.

play itself is not only useful but primally so. The very uselessness of the activity itself must mean that the state of mind is somehow crucial for us mammals, or it would have been weeded out by evolution long ago. He introduces husband-wife research team Johanna and Robert Fagan who studied play in grizzly bears. The Fagans found that the individuals who played the most were the most effective at surviving.

Why would play lead to a better chance of survival? It has everything to do with that organ in your skull. Neuroscientists Sergio Pellis and Andrew Iwaniuk and biologist John Nelson figured out that there’s a link between relative brain size and playfulness. They looked at the brains of 15 species and found that species with larger brains (relative to their body size) played more. Even more intriguing, John Byers has carefully studied several species— while more research is needed, Byers believes play allows mammals’ brains to make sense of and “sculpt” themselves.

For me, and perhaps other readers with a feminist bent, one of the most provocative parts of Brown’s book and argument is his rendition of the well-known Marian Daimond research on rats growing up in an ‘enriched’ environment. What made for an enriched environment? Toys and companions, in other words, play. Diamond figured out that the rats who played the most developed bigger, better (more complex) brains. “’The combination of toys and friends was established early on as vital to qualifying the environment as ‘enriched…’” So why did Diamond call these rats enriched instead of playful? “‘Back in the early 1960s, women had to struggle to be taken seriously as scientists,’ Diamond said. ‘I was already seen as this silly woman who watched rats play, so I did avoid the words ‘toys’ and ‘play.’“

Brown says, far from being silly, whether we are talking about young or old mammals (including the human kind) “The truth is that play seems to be one of the most advanced methods nature has invented to allow a complex brain to create itself.” In a misogynistic culture, it doesn’t take a big logical leap to move from the denigration of children spending time playing with the women whose days most often pass in overseeing and engaging in this child’s play to the denigration of grown-ups spending (wasting) time doing anything that resembles those women and children, outwardly or emotionally.

Think the kids whose parents can afford one high dollar league or lesson after another have an advantage? Not according to Brown. It turns out that, in denigrating play, especially the unstructured kind, we might have been setting ourselves up for underdeveloped, less creative and effective adult brains, both cognitively and socially.

Why is unstructured play important? The need to make up and sort out “rules’ appears to be a necessary ingredient for helping us develop a sound moral foundation and key capacities like impulse control. The purported lack of unstructured play in many youngsters’ lives does not bode well for their future functioning.

I think about my own play history. By all measures, I was and am a person with a wicked case of ADHD but it never quite got in my way. Which means, despite being able to check off almost all of the symptoms, “disorder” is a misnomer. I experience myself as requiring a different, more frenetic, variable, and physically focused sort of order and I somehow managed to come up with work-arounds and avoid pissing off all the grown-ups.

Now, I grew up solidly middle class with a single-mother who earned a decent family income. I had enormous privilege as a child. No doubt my mother’s Rousseauian, let-the-kid-be-who-she-is attitude helped with self acceptance. But I’m convinced it was the application of her parenting attitude combined with the freedom to run and roam alone and with friends, sometimes traipsing miles through the woods near my suburban home as we honored our urges to learn and imagine and move together. That was probably what saved me. The skills I accidentally developed helped me understand how to escape ostracism and trouble by coming up with ways to accommodate most of the important rules and my own uncontrollable impulses towards movement, challenge, action, stimulation, and adventure. Brown doesn’t touch on income, access, and racial differences, and I know full well how fortunate I was to have those woods behind my tract house in the suburbs. But, if Brown is right, regardless of other challenges, less adult-supervised soccer and more pick-up games or fort building and imaginative play time in safe parks and patches of woods with no grown-ups anywhere might be good for us as individuals and for society as a whole. Access to places for children to move their bodies together, to explore, discover, and lose track of time in unstructured play starts to look like a basic human right.

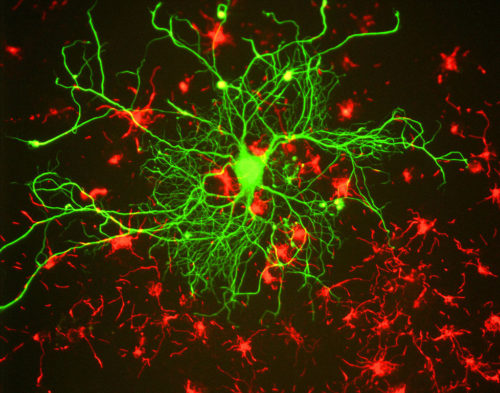

Maybe you’re convinced that play is good for developing children’s brains but still feel suspicious of playful adults? After all, our adult time is valuable (read remunerated) in ways children’s can’t be. Brown lays out the facts of our brains. Unlike many mammals, we have an exceptional capacity for brain development and neurogenesis (making new neurons) over the whole of our lifetime. While children definitely have a need for more playtime than adults, we are, according to him, evolutionarily engineered to need life-long play in order for our brains to continue to grow and develop in the ways that keep us happy and healthy. He says “the opposite of play isn’t work.” It’s depression.

of playful adults? After all, our adult time is valuable (read remunerated) in ways children’s can’t be. Brown lays out the facts of our brains. Unlike many mammals, we have an exceptional capacity for brain development and neurogenesis (making new neurons) over the whole of our lifetime. While children definitely have a need for more playtime than adults, we are, according to him, evolutionarily engineered to need life-long play in order for our brains to continue to grow and develop in the ways that keep us happy and healthy. He says “the opposite of play isn’t work.” It’s depression.

He argues that finding play-states at or during work makes us better workers and that play is, in fact, “essential” to doing the highest quality work. He recounts the play histories he took of two Nobel laureates, neuroscientists Roger Guillermin and polio researcher Jonas Salk. Brown writes ”I realized that what they were doing every day in the laboratory was playing. When Roger took me through his laboratory he was like a kid as he described his experiments… Their play was esoteric and difficult to understand for most people, but activity and the joy were the same as they would be for a kid in a sandbox.”

And then Brown drops what I found to be a beautiful prompt for anyone feeling stuck in finding or deciding on a new direction for their work life. “The work that we find most fulfilling is almost always a recreation and extension of youthful play.”

I can hear the protests now (because I’ve heard them so often, many times in practiced, full-throated, choral unity as my inner demons opened up to unleash a new wave of self doubt). Play is fine for some people but most of us have to settle down to the grim business of boring adult reality. And, let’s face it, the houses, roads, and office buildings, the passive entertainment and scales of efficiency and all of the other infrastructure we’ve built have not been designed to maximize our capacity for play, for utter delightful absorption in and satisfaction with the present moment. In many cases, they’ve been designed, intentionally or not, with effects that are quite the contrary. Much of our built environment maximizes our capacity for wanting more which, in our boxed-in longing, we often interpret as a wish to purchase more amenities for the cages that limit our creative vision and movement in the first place. The amenities we pay for in money (abstracted life time) rarely change our longing in any enduring way and the cycle of working to not meet our needs continues as the days come and go and we remain, in John O’Donohue’s words (see Play Time part 1), victims of time. Brown takes a shot at understanding where some people get stuck and where some of the angry resistance to prescriptions of play come from. “When some unhappy people hear the message about the importance of play,” he writes “they get angry and defensive, realizing what they’ve missed.”

He’s careful to point out that you don’t have to quit your job or become a Nobel laureate. Even just occasional play might help get you reacquainted with the feeling and could, with practice, become habit-forming. So how do you cultivate a state of play? If Brown is right, play can happen under many circumstances and according to individual preference but there are some that are particularly conducive.

Moving your body in playful ways (dancing, racquetball, drumming or dancing with gusto) “lights up the brain and fosters learning, innovation, flexibility, adaptability, and resilience. These central aspects of human nature require movement to be fully realized. This is why, when someone is having a hard time getting into a play state, I have them do something that involves movement: because body play is universal. As Bob Fagan says, ‘Movement fills an empty heart.’”

One of the impulses that led me to undertake the Waves to Wisdom project is a deep intuitive  knowledge, developed through years of experience, that combining some intention and guidance with what Brown calls “movement play,” particularly when it takes place in or near the water, has the potential to deepen the meaning people perceive in their lives and to rehabilitate our relationship to our own time. Play can allow us to rediscover that each day has the potential to be filled with kairos, not just paced off in chronos.

knowledge, developed through years of experience, that combining some intention and guidance with what Brown calls “movement play,” particularly when it takes place in or near the water, has the potential to deepen the meaning people perceive in their lives and to rehabilitate our relationship to our own time. Play can allow us to rediscover that each day has the potential to be filled with kairos, not just paced off in chronos.

For so many of us, the combination of reflection, a few challenging existential questions to ponder, some low-stakes creative undertakings, and ocean play can prompt new metaphors that synchronize previously competing urges, reveal inspiring juxtapositions and connections between seemingly separate facets of our one life. Immersion, literal and figurative, in this sort of play can change previously petrified, self-limiting beliefs about what is possible. Play in a higher power (like the ocean) offers embodied experience and guiding metaphors that render those limiting beliefs fluid or dissolves them entirely. Sometimes people come out of these experiences with a dramatically new idea for their lives or work. More often they find layers of potential for meaning and joy, for really living their day and night times. They see and articulate meaning and purpose that have coursed through their lives all along, unnoticed or unappreciated. Brown sketches out what our brains have to gain. While there’s no guaranteeing precisely what each person who plays deeply will come away with, we know what they have to go in with, an internal motivation.

He writes, “Authentic play comes from deep down inside us. It’s not formed or motivated solely by others. Real play interacts with and involves the outside world, but it fundamentally expresses the needs and desires of the player. It emerges from the imaginative forces within. That’s part of the adaptive power of play; with a pinch of pleasure, it integrates our deep physiological, emotional, and cognitive capacities. And quite without knowing it, we grow. We harmonize the influences within us. Where we may have felt pulled in one direction by the heart and another direction by the head, play can allow us to find a balanced course or a third way.”

I understand. It isn’t easy.

One of the reasons I and so many others spend a chunk of our chronos here, in this jungle village where I’m writing the final draft on a dusty keyboard as sweat drips from me in the dead of North American winter, is the kairotic potential of this tropical place. Take those sunsets. Most of us are, wait for it, out there without our phones. Now, you still see plenty of humans curved down over their gadgets but, just as often, those who did bring phones are looking up, necks arched to hold heads high, to take in something beyond the screen. Often those screens are then lowered, the photographer giving way to the subject, surrendering neither to the bound, segregated sensory world of the phone camera’s view, nor to the seconds and minutes that too often tell us whether it is time to eat, to rest, to love. I see it every day that I take my own camera out there, the other photo snappers putting the phone down for awhile and letting their awareness move with the planetary rhythm of time, of changing light. I see them lose track of it all and let their senses come alive in connected response to the shifting of what’s beyond. You can almost see the barriers dissolve— we lose a little of the lonely existence of individuals and join with Others out there, human and aquatic, biological and geological, planetary and cosmological. Sometimes they (and I) photograph out of that feeling or try a new maneuver on our surfboards that, if we pull it off, will send an arc of spray up in the lovely light, or we swing our children into the water or bring them to tide pools to give them the richest life imaginable. And then sometimes we just stand there and feel it, alive in our own bodies and their time, letting all of our senses and our unfolding history flow into our vision. And if we do make a beautiful photograph, or execute a new maneuver on a surfboard, or elicit unbridled laughter from our child in the midst of that moment, well, as far as I’m concerned that is at the heart of what art at it’s best is all about anyway.

The belly of the high cirrus cloud bank that descends from just above the setting sun down to the point at the north end of this Pacific bay has just started to go pink. All day I’ve watched the clouds in the sky, rare in this season. I’ve hoped some would remain as I measured the day’s events by the coming time for me to I bring the camera down for immersion in the warm evening light-bath. The sun has receded behind the ocean now and a pink stroke of cirrus in the sky saturates as the light is bent by the atmosphere, only allowing the longer, redder, warmer wavelengths through, making them take their time to get to us and our eyes, now all pointed in one direction on this beach. A rippled, ascending cloud is reflected in the wet sand, now exposed by the receding tide, the closest thing the ocean might have to a second hand. The horizon between these pink diagonals now forms the shaft of an arrow pointed towards what my eyes perceive as gathering obscurity in the darkening east. The light during and after sunset often brings me to some emotional shore where tears wash onto giddy laughter and, judging by what I see around me on the beach, I’m not the only one moved by the spectacle, not the only one whose time has been touched. When the last point of the orange sun disappeared below the line of the distant ocean, people applauded.