Mary Oliver made a sacred practice of her direct sensory experiences, her intimate bodily connection to her place and days. And then she did the hard work of crafting some altered but analogous version of those experiences, rendered through lines on a page. She made us feel what she sensed. Then, at least for her dedicated students, she inspired us to go out and be passionately sensory in our own bodies, to make sense of the world for ourselves.

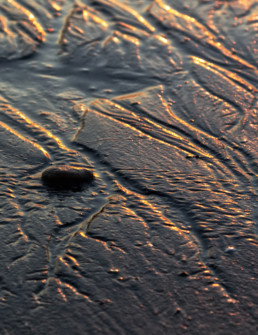

This morning I carried my surfboard across the sand towards the water as the sun came up on the other side of the hill behind me. It’s one of an arc of foothills ringing this white-sand Costa Rican beach set deep in the jungle. As I walked, I looked out to one of my dear friends, L, already in the water. I am often aware of the difference between us. She’s significantly younger and, at this point, stronger than I am. She’s German and speaks English, thereby allowing our friendship. I’m American and (despite a LOT of Spanish DuoLingo) still just speak English. She’s one of the few people I know who loves to share waves with friends as much as I do. I treasure every session we have together. The walk to surf is always thrilling and often at least a little bit scary. Heading out to ride waves with loved ones adds a primal tribal thrill to the experience. We are here. Today, the instant the first wave ran over my feet, the sun crested the mountain and L was suddenly bathed in intense warm light. Now there were two of her, one whole, embodied version and another, equally clear and colorful liquified reflection undulating, spreading, and shrinking in chaotic lyrical patterns on the water beneath her. I remained in shadow of the mountain as I walked deeper into the water. For a few delicious seconds, with someone I love out there, in another world but deeply connected, her fleeting moment in light and mine in shadow helped me sense something about life and death, about love and age and loss and, above all, about beauty.

John O’ Donohue said that in the presence of beauty we feel more alive. Beauty, he said, is quickening, not deadening. If he was right (and I believe he was), then Mary Oliver was among the truly beautiful humans of my era. I suspect I might have said that was true before last week, but the collective pain and celebration of her death lent texture to that truth. She made so many of us feel more alive. She wielded what looks to me like a powerful sort of magic. She made a sacred practice of her direct sensory experiences, her intimate bodily connection to her place and days. And then she did the hard work of crafting some altered but analogous version of those experiences, rendered through lines on a page. She made us feel what she sensed. Then, at least for her dedicated students, she inspired us to go out and be passionately sensory in our own bodies, to make sense of the world for ourselves.

She communicated her amazement, her knowledge of how to pay attention, through plain language, alchemically transformed into powerful incantations that conjured a world fully populated by sensuous others, this grasshopper and those wild geese, a hungry bear and swollen blackberries. Each seemed to enter our brains in numinous phrases that, in turn, filled our bodies with something so potent that those lines could shift a day. With enough reads, they could shift a life. An intensely private person, she worked in a way that built a community broader and deeper than I’d known before last week. Her power turned the understandable, hopeless, endless streams of social media outrage at the outrageous into a moment of collective pain with beauty, not vitriol and fear, at its center. Despite a difficult childhood, her work never, not once, indulged in self-pity.

I don’t believe the thought ever occurred to me, that Mary Oliver was going to someday die. This week, the week she left us, I’ve been thinking about little else. There is Upstream, which I devoured and revisited like a brilliant, new, love-at-first sight friend. And those last books and poems, many of which I’ve not yet read— she might have died before having gotten to those. So, in addition to an unexpectedly profound grief, I am swimming in gratitude for her. I clearly failed to recognize my own attachment to her as a living being. I began writing this, the week she sensed her last day, surprised to find myself falling into grief. After all, most of the writers I love are dead. I never met Mary Oliver. She almost never gave interviews and I knew almost nothing about her life except that she made a habit of walking early with paper and pen, courageously built a life with the women she loved, taught college writers for awhile, and had an almost eerie capacity to write what I most needed to read. I only heard her for the first time a few years ago, when she released a cd of readings, called On Blackwater Pond. By then her voice was that of a much older woman than almost all publicly available photographs of her, except the often reprinted portrait of her as a youngster, the one taken by her partner of decades Molly Malone Cook. The few Mary’s I’d seen, young, suddenly middle-aged, then old, punctuated the fact that her life had occurred somewhere hidden. Meanwhile her sometimes denigrated work poured out into the public that I felt fortunate to be a part of. I didn’t know her and still have just as much of her as I ever did. I have her lines on a page. And yet, here I am, grief-stricken.

A few days after she left us, there was a total lunar eclipse— a Blood Moon. I watched the eclipse near midnight, lying with L and many strangers on a dark, windy beach in the northwest of Costa Rica. Like Oliver’s death, the eclipse was a surprisingly emotional experience. I have seen several but they never fail to move me. Despite thinking I’m ready, I always go in unprepared, and come out surprised. Last week I lay on that beach, pelted by fine grain sand working its way into every orifice, looking up through the binoculars provided by a well-prepared German I’d never met and couldn’t recognize now (“Fernglass, anyone?”)

I watched as the eclipse turned “total.” The moon was red with the thinnest leftover losenge of reflected white daylight on its left side, like an opening parenthesis promising a useful aside. I lay there open, in a way I’ve long practiced, ready to sense and learn something. I owe that sort of receptivity in large part to Mary Oliver. And learn I did. I could, in that instant, finally feel why each eclipse is so affecting and maybe Oliver’s death too- similarity across scale.

Fractals are … are nearly everywhere you look in nature and even in those organs doing the looking (the wild, spherical landscape of your eyeball). Coastlines and clouds are fractals and so are trees and your circulatory system. A tree is a fractal because the trunk, branches and leaf veins continually repeat the pattern of dividing into smaller and smaller, self-similar shapes. Your circulatory system is also a fractal. Your aorta is fat then branches off repeatedly into thinner and thinner vessels as the recursive pattern (and nourishment it allows) reach towards the edges of your body.

There’s a shape in mathematics (stay with me here!) called a “fractal.” We all know many fractals, and have known them for far longer than there has been an English word or any math attached to them.

The fractal foundation defines fractals as

infinitely complex patterns that are self-similar across different scales. They are created by repeating a simple process over and over… Driven by recursion, fractals are images of dynamic systems – the pictures of Chaos.*

Fractals are complicated (even chaotic) patterns arising from simple, repeating processes. They are nearly everywhere you look in nature and even in those organs doing the looking (the wild, spherical landscape of your eyeball). Coastlines and clouds are fractals and so are trees and your circulatory system. A tree is a fractal because the trunk, branches and leaf veins continually repeat the pattern of dividing into smaller and smaller, self-similar shapes. Your circulatory system is also a fractal. Your aorta is fat then branches off repeatedly into thinner and thinner vessels as the recursive pattern (and nourishment it allows) reach towards the edges of your body.

I only learned what fractals were after becoming obsessed with them as a photographic subject. I knew that that recursive shape was beautiful, that it looked like life. It made perfect sense when I finally learned a little about the geometry. And it didn’t just do so in the intellectual way but as David Abram says, things that make sense enliven the senses. That night, for one of the first times in my life, watching that eclipse, I could feel the math. I could sense similarity across a vast difference in scale. My pounding heart joined the percussive chorus of pelting sand and the distant mathematical music of those spheres (sun and moon) working with the earth, supporting me as it put on this show. It was revelatory that the earth, a body larger than my own tiny mind can imagine, was moving through light and casting a shadow just like my body does. I could see it happening. In that moment it was hard to not feel like a part of the whole, a small, sensing section of the cosmos with just as much right to cast a shadow as the earth itself, just as much freedom to be carried by wind as the sand. With my heart opened by sadness and quickened by beauty it was possible to feel like, in my own humble way, perhaps on scale difference about on par with the difference between my body and the earth’s, I have been making my own kind of Oliverian beauty. I have been living “one wild and precious life” spent as “a bridegroom taking the world into my arms.” Mary Oliver had, in her work, given me permission and guidance to take the million steps that got me to that beach, looking through a generous stranger’s fernglass. Because of Mary Oliver, I felt free. After a lot of doubt and many wrestling matches with shame, I felt free to accept that this precise sort of experience as the foundation of my work in the world. Rooting intellectual and spiritual learning in the sensuous world is at the root of the most powerful form of service I can offer others.

But in the years before I knew her poetry, it sure didn’t feel that way. By any measure, as a child and adolescent I would have been diagnosed with attention deficit disorder (had it been available, or my mother capable of entertaining for a fleeting moment that there might be anything disordered (as opposed to extraordinary) about me. Equally intolerant of disapproval, sitting, or being told what to do, I spent my early adulthood mostly going through the motions of my formal education. When freed from that, I wandered around what I was pretty sure were enchanted woods near my North Carolina home, splashing through creeks that felt like friends. When I got a little older, I added taking pictures to the journeys, so that even when I was in I could relive the reverie of being out.

I taught myself the technical aspects of film and darkroom photography through a series of three books Ansel Adams wrote. I spent time every single day staring at reproductions much more lavish than anything I could then make in the darkroom. I devoured biographies of the great modernist photographers I admired, Imogen Cunningham, Edward and Brett Weston, Ruth Bernhard, and Tina Modotti. Their stories of visible achievements earned by their own traipsing with cameras, slaving over prints and, most of all, finding teachers, guides, sometimes one another to help them develop their skills and vision, infected me with a ravenous hunger for a mentor who might help me figure out my confusing life. I spent years searching feverishly for a guide, an older person who was out there doing what most people I knew probably characterized as wasting time, exploring the natural world without an agenda of expertise. And then, later, crafting beauty. I wanted a guide who spent her life staring, trying to really see already beloved places, to know them fully in some carnal, intimate way. That, after all, was how I’ve lived most of my life as a photographer. I was pretty sure everyone I knew must be judging me harshly for it. The self torture was senseless— I was too young to know no one really cared what the hell I was doing with my time.

And I really didn’t have any choice about how I went about that work anyway. Only after I felt the flower, the creek, the rock, the wave had somehow entered me, that the subject had allowed me some sort of communion, only then did I feel it was polite to get the camera out and make something I could take away and show others. Although all that seemed like a childish habit to hide, to be ashamed of, in my early 20s, I knew I had no choice but to be out there doing just that. If I’d not been afflicted by a bad case of needing to be a good girl, I might have rebelled outright but I was looking for a work-around and permission from someone in authority. I was entitled enough to feel like I should be able to be unconventional with approval. I wanted an elder human whose life looked at least remotely livable who I could ask the hardest questions and who might give me some indication that they understood and cared what the hell I was talking about, that it all mattered, that I was okay and just needed to keep working. I never found that person in the flesh and spent too much time feeling either terrified or sorry for myself for about a decade.

Then, somewhere along the way, I was given a copy of New and Selected Poems by Mary Oliver. It came out in 1992, right about the time I became a full-time professional photographer. I’d been an English major and had read plenty of poems, plenty of nature writing. I had (and still have) a dogeared Walden that I carried around with me nearly everywhere. But I had never been schooled by another human like I was in the time I’ve spent with Mary Oliver. She taught me that the precise sort of hyper-focus on what was most mesmerizing and the desire to fall passionately in love with the most minute parts of place (specimens, some might call them) was not a disorder, or didn’t have to be. It could be the foundation of making, or entering something beautiful. Her arresting, deceptively simple writing made me see that if you worked on making something out of what you learned in the heat of the passion that characterized those experiences, you could create a life that could be quickening, not deadening. And, if you found ways to repeat the tiny, sacred patterns on larger scale as you went, perhaps the beauty you made would not just be for you but for someone else, maybe even several someones else.

In short, Mary Oliver helped me get over myself and focus on creating meaning out of the magic of being alive. Over the next few years living with her lines as part of my days, I came to understand what has become one of the guiding principles of my own life. Inspiration is sacred and, metaphorically, a calling. The power of the planet as a whole and of the human-scale habitat we occupy, the gravity and fluids and fractals that give our beleaguered, paved-over, cut down world and our own bodies their multiplicitous shapes, that power deserves our focus. And, regardless of the source of your inspiration, if you can find ways to translate your focus, your joy, and love into a substantial offering, if you can somehow recognize your gifts, whatever those happen to be, and augment them with skills so that you can someday serve someone else’s need for meaningful focus, for nourishing attention, for meaning, and beauty then you might even be better than okay.

Why hadn’t the other naturalists and nature writers I’d read, especially Henry David Thoreau, done that for me? That question has lodged in my head since Oliver’s death and I think the answer might be especially relevant to our current political, cultural, and environmental moment. Intellectually, his sort of dedicated observation seemed superficially similar to what I was

unconsciously cultivating as I tried to figure out how to be by walking through rivers and developing film, but it felt almost opposed. Thoreau, it seemed to me, was making an argument that wilderness was the solution to a human problem. I was not looking for wildness, which suggested some sort of insurmountable gulf of difference between me, a discontented product of civilization, and every other thing out in those woods. I was looking for (and finding) intimacy, connection and belonging, a means of ending, once and for all, a lonely isolation behind some barrier I just couldn’t shake no matter how good or easy or privileged my life was. I needed a dissolution instead of a solution.

There’s one line from Walden that I think might get at the heart of the difference between these two writers and, in turn, the difference between one way of many of us unthinkingly approach our lives and one another. Thoreau often wrote with a voice that emphasized his expertise and assuredness, and he had plenty of both! When he evoked the animal, sensing part of him, it was often in opposition to his humanity.

“I found in myself, and still find, an instinct toward a higher, or as it is named spiritual life, and another toward a rank and savage one, and I reverence them both. I love the wild not less than the good.”

Thoreau’s writing promised transcendence and a superior way to live, as opposed to all the poor saps in bigger houses with day jobs. Wilderness could save you. Don’t get me wrong, I loved what he wrote and even spent five years in a cabin in the woods with no bathroom, living out my own version of Walden.

But, in retrospect, I believe that the desire to achieve some kind of transcendence (and implicit superiority over all this business of every day life) and the agony of the certain knowledge that I was so flawed, so prone to inattention, and likely to fail at being an expert grown-up didn’t help me one bit. I knew enough to know that I didn’t just need abstract knowledge, that studying anything in disembodied form wouldn’t stop the fear or bring the connection. I grew up in a place where waiters were likely to about to have (if they didn’t already have) PhDs. I saw experts everywhere, but so few people living a life that looked all the way alive.

But Oliver wrote with such humility and a passionate, intimate continuity between what she was and what she sensed in the other. In poem after poem, she defied all my expectations about books and writing. She was never the world’s superior, often its supplicant. Just to pick one of many examples, in Luna, she wrote of her encounter with a moth, an individual possessing and fulfilling its purpose during a few short days and she felt no need to neatly order and classify it, to identify it as one of many Actias luna.

Of herself in this meeting with the moth she wrote

I live

in the open mindedness

of not knowing enough

about anything.

Seeing the moth dead “hurt her heart,… another small thing/ that doesn’t know much.”

And while Thoreau boasted about his life well-lived, time, for Oliver, often seemed scant. There was no amount of life in the woods that would save the lover from the grief of losing the beloved too soon.

Even the summer “also has its purposes/ and only so many precious hours.”

She saw value in grasshoppers, not just as specimens in a system (genus/species) like Thoreau had. Instead she was concerned with this grasshopper, the one she could touch, the one who also looked right back at her, with its own agency and the vision of “enormous and complicated eyes.”

In retrospect, that book of poetry I stumbled on in the 1990s turned Oliver into the mentor I was looking for. Her writing helped me dissolve that barrier I’d carried around since I was a teenager. As a result, I got a lot less lonely and self-absorbed and a lot more generous and receptive. With her help, wild and good became indistinguishable.

Later, when I unexpectedly fell passionately in love with teaching and I found myself playing the very role I’d never found anyone to fulfill for me, I realize the gift Oliver had given me was magnitudes of order greater than I’d thought. As desperate as I’d felt to find someone I could trust to tell me I was okay, I discovered the reason to find a mentor is not so you can be okay. That’s only a fraction of the story, one vein in the recursive pattern. Mentors allow you to develop the wherewithal to guide others, to show them that they are, in and of themselves, as okay as any mortal can be. That they can let the soft animal of their bodies love, that their life is, in fact precious, and that being idle and blessed (at least as Oliver clearly was) isn’t as easy as it sounds but that no thing is more worthwhile, especially if you can build from those moments some form of service or calling. As you help others find their place in the pattern, you create your own.

This month saw the death of a beautiful mentor, a guide, another human who loved and looked hard, who labored and lost and grieved and then transfigured all of that life into writing that reached so many of us. As dependent as I am on walking into and feeling water, on seeing light and shadow, on learning directly through my sensual existence, I can’t imagine the last 25 years without those poems. They helped me recognize that the deep attention demanded by love, in any form, of a friend, a partner, a moth, a wave, work, or play, is the most abundant, generous, exacting, and profound teacher we can learn from. I could repeat her lines like incantations, those patterns of observation, of passionate receptivity, and offer them to so many others who, in turn, could feel they were, flawed though they might be, a part of “the family of things.” LINK Over and over, the aortic abundance of Mary Oliver’s work gave me a pattern I could adapt and repeat. It lent dignity to the tiny branch of beauty I was working to create. She offered her life in service of the most disciplined, lovingly crafted version of her intimate moments and, in turn, offered me my own. Grief does seem the only human, the only beautiful response. As much as my thinking homo sapiens brain knows better, this was a month when it felt like the moon and earth, the sand and the shadows and the surf, all bowed their heads to acknowledge the loss.

If you’re interested in setting up a free, no-obligation conversation with Maia about coaching, mentoring, or a custom retreat, email her at maia@wavestowisdom.com.

- Check out Ron Eglash’s fascinating TED talk about fractals at the heart of African designs