Waves to Wisdom: A bit of historical context

Aloha

Non-surfers could easily conflate the word with other surfing-born colloquialisms.

Gnarly, Dude.

But aloha, according to a contemporary Hawaiian statute, “is more than a word of greeting or farewell or a salutation”, it’s a system of ethics, a set of core values.

”Aloha” means mutual regard and affection and extends warmth in caring with no obligation in return. “Aloha” is the essence of relationships in which each person is important to every other person for collective existence. ”Aloha” means to hear what is not said, to see what cannot be seen and to know the unknowable.”

That sounds a lot like a wisdom practice and a bit like faith.

In so many of our lives, we slowly lose the joy, wonder, presence, and unending accomplishments of simultaneous growing-and-being in childhood. Most of us have been in work or personal communities where we can see or feel that there’s a grim, plodding, almost disembodied sameness. An invisible routine that feels like it is monopolizing some cosmic remote control, keeping life’s channel tuned to something that’s mostly boring for everyone. I’ve seen this phenomenon play out countless times among both my mid-life peers and the college students I’ve watched transitioning to adulthood, or to “better” career opportunities. We so often cling to literal youth as if we aren’t all capable of having increasingly delightful figurative youths—of renewing joy, of becoming more beautiful as our eyes grow with seeing the light reflected into them from patterns we can come to recognize but never control or predict. Clinging. Boredom.

One of the working theories of Waves to Wisdom is that it doesn’t have to be that way. In this second half of life, I had the tremendous good fortune to discover that surfers are also governed by routine, but it offers the return on investment of a carefully studied discipline. They are led by invisible forces and controlled by remote powers but, at least for some of them, the breaks that are a local manifestation of invisible, distant forces come to tie them into something much bigger than themselves, something powerful and universal that dissolves the boundaries between work and play, present and past, and even between sadness and joy, each prompting gratitude, a deeply attentive outlook, and a fluid creativity.

Waves to Wisdom is all about the beach, the littoral zone where waves break. But it’s also a metaphor. It’s about finding your perfect wave, which might, or might not be made of salt water.

This endeavor is part of a long history (and much longer traditions) of board riding and humans who played hard and learned deeply from the ocean and its waves. We certainly haven’t all been wise. There will be more about the history of surfing and surf culture in coming posts but for now, here’s an aloha-inspired introduction to some of how modern surfing caught on, how it came to seem natural for it to be dominated by white males, and how ancient surfing, he’e nalu in Hawaiian (literally, wave-sliding) became so popular and appeared so adventurous that even I, then a landlocked almost 40-year-old, had spent a lifetime aspiring to learn to do it.

Endless Misinformation

There are 27 million of us surfing people who inherited and contribute to the now trans-national, contemporary culture of surfing. This culture, one that has welcomed (and by turns resented) many thousands of other new surfers each year, is dominated by one historical event. The year is 1964. Three white, male California surfers, Mike Hynson, Robert August and filmmaker Bruce Brown, buy around-the-world tickets and set out on a grand adventure with a simple, ambitious goal, to make a surf film. Often classified as a documentary, the iconic but largely staged Endless Summer came out in 1966. Brown had a hard time talking anyone into distributing his movie, so he rented (and sold) out theatres in Witchita, Kansas and New York City. I deeply admire his chutzpah, in addition to his story telling. Non-surfers embraced the adventure tale focused on recreation and the most liberal audiences of the day took no notice of the seemingly benevolent colonial attitudes and unconscious racism of the narration. New Yorker film critic Pauline Karl loved it. For that matter, I love it!

Kael and I are in good company. The film was a huge hit. What was not to love? The surfers, as portrayed in the narrative, have only wholesome impulses to search for and ride waves, and occasionally look at pretty girls. They have freedom to explore, and not a care in the world. Kennedy was assassinated while the trio was traveling but there was no hint of the American tragedy, or any tragedy. A sequence from Africa includes a shot of promoter R. Paul Allen, dressed as a warrior in blackface. Brown narrates the initial sequence of the surfers in the Ghanaian surf with a comment about no surfer having surfed, or even seen, the waves. The visit to South Africa includes a wry comment about sharks and dolphins not yet integrating. There’s no hint of the escalating involvement of America in Viet Nam, although Mike Hynson was on the trip, in part, to avoid being drafted. A sliver of the surfers portrayed in the movie are women but they (and the women who stay on the beach) are offered as eye candy for the straight male viewer, not as rippers in their own right.

To this day the tropes and trends of contemporary surf culture are profoundly influenced by Bruce Brown and his Endless Summer movies. The international surf tourist, the white male penetrating virgin territory, the perfect wave. We can’t thank (or blame) Brown for them- he was just being who his world led him to be, something we all do. His movie is an enduring success, still finding audience with an appealing sequel, released 30 years after the original. But it’s hard not to wonder, as writer and editor Sam George did in the 2011 documentary White Wash, what would have happened if Bruce Brown had done some research into primary historical sources and let those guide his narrative? What would have happened if we knew that all of the early surfers came from populations most Americans would not classify as “white?” Or if the film has offered us a bit of the Hawaiian surf history and legends in which women played a role equal (if not dominant) to men’s? Or if Brown had clued us into the fact that black South Africans were forbidden from entering most of the beaches where the early South African surf scene developed. Of course, when Brown narrated his film he was a filmmaker supporting his surfing. He showed movies in small auditoriums and had no idea of the coming influence his work would have. Plus, Mr. Brown didn’t enjoy the benefits of a post-1960s education or hindsight. History matters and, to complicate things, we don’t have nearly enough native wave-sliders’ written accounts of the past.

“’Aloha’ is the essence of relationships in which each person is important to every other person for collective existence. ”

If we only attend to what happens after we arrive, we miss a lot. As it turned out, people had been riding waves on the Ghanaian coast for a very long time before and before Hynson and August surfed “the perfect wave” at Cape Saint Francis and long before the first man of European descent stood on a surfboard. A European named Michael Hemmersam, who undoubtedly, didn’t know what he was seeing, wrote in 1640 that parents on the African Gold Coast “tie their children to boards and throw them in the” surf in order to teach them how to swim.” A couple of centuries later, in 1861, Thomas J. Hutchinson wrote this passage about the West African Coast:

“During my few days stay at Batanga, I observed that from the more serious and industrial occupation of fishing they would turn to racing on the tops of the surging billows which broke on the sea shore…”

For a list of accounts of Europeans witnessing wave-play of various sorts in Africa prior to the Endless Summer, go here.

And then, of course, there were the Hawaiians, for whom surfing was so much more than recreation. Tied into sex, class, legend, and spirituality.

Christian missionary William Ellis wrote in 1822

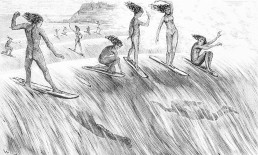

Sometimes the greater part of the inhabitants of a village go out to this sport [surfing ], when the wind blows fresh towards the shore, and spend the greater part of the day in the water. All ranks and ages appear equally fond of it. To see fifty or a hundred persons riding on an immense billow, half immersed in spray and foam, for a distance of several hundred yards together, is one of the most novel and interesting sports a foreigner can witness in these islands.

In a 2011 book Waves of Resistance (public library), the first history written from an indigenous Hawaiian perspective, Isaiah Helekuhini Walker sheds a great deal of light on how the dominant views of contemporary surfboard riders have little to do with the sport’s ancient Polynesian roots

For one, although men certainly surfed, “female surfers were far more popular in Hawaiian histories. (Walker, 17). The story Walker tells revolves around the importance Hawaiians placed on the importance of respect, both mutual for one another and for the land and ocean that sustained them. He cites the work of anthropologist Tevita O. Ka‘ili who studied Tongans living in Hawaii and wrote about the concept of “vā,” or social space, emphasizing the crucial role of nurturing the social spaces between people in any trans-national, mobile culture. Trans-national mobility and, more recently, a backlash against it, defines so much of what we are born along by, wrestling with, and, hopefully, learning from these days.

I began surfing at 40. I’m now 51. In surfer years, that makes me 11. I still have a lot to learn about past and possibility.

I’m a 51-year old American woman who believes she is white. Most of my surfing is done in North Carolina, and, more occasionally, California, Costa Rica, and a couple of other spots. So why worry about aloha at all now when America has developed and exported its own culture of surfing? Why spend time thinking sexism or race when I’m surfing? Surfing is the best thing, the most fun, the most personally rewarding activity I’ve ever engaged in. Understanding why every line-up I’ve ever paddled into looks like it does seems crucial.

Hawaians say “Nana i ke kumu” which translates to “pay attention to the source.”

Further Brief Reading:

Isaiah Walkers article about women’s surfing in The Inertia here.

The Bishop Museum’s brief entry on surfing here.

Stokeshare’s entry on the history of surfing here.

In addition to Walker’s book, for more extensive historical accounts:

Scott Laderman’s Book Empire in Waves (public library)

Jon R K Clark’s book Hawaiian Surfing (public library)

Timothy Tovar DeLaVega’s Book Surfing in Hawai’i: 1778-1930 (public library)