Too little time? Too many things?

Try a float tank to explore an interior landscape with a saltwater fix, even if you’re city-bound, landlocked, and only have an hour.

Do you miss the saltwater?

Even for those who live at the coast, our daily lives and the time pressures we all accept as part of responsible adult life so often keep us from the places that rejuvenate and inspire us. Somewhere along the way, we assented to a push of priorities that prevent us from getting the daily (or even weekly) dose of mystery and beauty that can render the routine sacred and turn boring repetition into disciplined discovery. When just a few minutes’ time creek or seaside could make all the difference there are weeks when we feel like we can’t (or won’t) find that time.

In his interview with the inimitable Krista Tippett the late, great philosopher and poet John O’Donohue said

I’d say seven out of every ten people who turn up in a doctor’s surgery are suffering from something stress-related. Now there are big psychological tomes written on stress, but for me, philosophically, stress is a perverted relationship to time, so that rather than being a subject of your own time, you have become its target and victim, and time has become routine. So at the end of the day, you probably haven’t had a true moment for yourself to relax in and to just be.

Waves to Wisdom exists to guide people into a more creative, fulfilling, and abundant relationship with their time. The littoral zone is the sandy frontier where the land and we terrestrial creatures cede control to waves and water, the planet’s dominant element. The place is filled with both dynamic facts and transformative metaphors. When you’re there, standing on that edge or, even better, floating just beyond it, everywhere you look there are wordless poems writing themselves in their own meter and cadence. Water reflects and refracts light and, in the process, mixes colors, composes passages, spits out short, fleeting lyrics that, if you’re fully present and attentive, can swell your heart. And, if the visual and aural reveries weren’t enough, there’s the feel of the place– the ephemeral motion that, if you let your body succumb to its rhythm and internalize it, can change your mind, your day, and your life.

The littoral zone is the sandy frontier where the land and we terrestrial creatures cede control to waves and water, the planet’s dominant element. The place is filled with both dynamic facts and transformative metaphors.

But what if you don’t live near the ocean? All water is liquid and chaotic and rhythmic according to forces that, by their very complexity, are mysterious to our perceiving minds. Even dry landscape has its own movement and, although the timbre is subtler, it still offers portals into what O’Donohue calls a “true moment.” But what if you only have an hour in your busy week? Don’t work or live anywhere near a natural landscape?

You might want to spend an hour in a floatation tank. I just experienced my first float, after hearing Dr. Justin Feinstein, neuropsychologist and director of the Laureate Institute for Brain Research (LIBR), present at the annual Blue Mind Summit. The summit is a gathering of people from diverse professions and backgrounds who gather to share information and camaraderie about their work in support of the theory that being in, on, near, or under water is good for human health, mental and physical.

Feinstein summarized his paradigm-shifting research into the mental health benefits of Floatation Restricted Environmental Stimulation Therapy (REST), or spending time in a dark, shallow bath of warm water with so much Epsom salt in it you couldn’t sink if you tried. He is accumulating mounting evidence that Floatation REST works better than any known drug to combat anxiety and depression. He’s also convinced it can provide crucial help to people fighting anorexia and addiction.

And it seems floating doesn’t just aid in just mental recovery. This straightforward, non-toxic practice with almost no unpleasant side-effects appears to aid recovery and relaxation after any sort of stress, including hard work-outs of your mind, body, or both. Powerful testimonials abound from people who beat eating disorders, Olympic athletes who recovered faster, even musicians who credited floating with enhancing their skills. I’d heard about float tanks for years but Feinstein’s talk left me resolved, once and for all, to get into one.

A week later I entered a TruRest floatation center through a nondescript door in a strip mall near my house. They call themselves a spa. The attendant ushered me down a hallway with dim lights and clean, neatly rolled towels on spare shelves.

I arrived at one of several private rooms, each with a shower and a smooth, white tank, lit within by rotating colored lights. The attendant walked me through the process, showed me the intercom button in case I needed help and offered a few options (tank door open or closed?, music on or off?, head resting on water or a little foam floaty?). Then she left me alone.

Squeaky clean, and earplugs inserted, I lowered into the 10-inch deep water with its 1000 pounds of dissolved Epsom salt. Some people suffer from claustrophobia so it’s not required to close the tank door but I wanted the full, womblike experience so I pulled the hatch closed, flipped the light switch and settled into the total, device-free sort of darkness we rarely experience. At my request, the soft music would stop after a few minutes and only begin again when my hour of floating was nearing its end. I tried a meditation technique I and many of my clients respond to right away, the full body scan. Just focusing on each part of your body in turn, feeling it in space, noticing it without judgment, then moving onto the next. In this warm water and the moist air, all calibrated to human temperature, it was difficult to tell where I ended and the world began. Instead of feeling lost, space and body somehow became one and, although my leg still felt like my leg, it and every other every part of me began to feel as though it encompassed a deep interior, larger, lighter, and more expansive than usual. My exploring mind had more room to maneuver inside my feet, then legs, then sacrum. With so much spaciousness and no external distractions, I soon felt a sensation I often have to work long and hard to achieve on the landward side of the littoral zone— a freedom from any desire to be anywhere else “better”, or to perceive something else more beautiful. It felt like my body and mind, even random thoughts that popped up here and there, they were all just me, not separated. Every thought and feeling was inextricably one, varied terrain in this small, dark sea– not good, not bad, just spacious.

It’s precisely this sort of moment of intimate connection between the body and the brain, and technologies to help bring this connection to the forefront of awareness, that is Feinstein’s and LIBR’s guiding principle. In that dark, buoyant place, experiencing as complete a sensory return to archetypal, maternal beginnings as I can imagine encountering with my adult body, the intimacy was undeniable.

I hadn’t felt like I was worried going into the tank but somewhere in the middle of the float, thoroughly relaxed in the darkness after less than an hour of this remarkable experience, as those random thoughts materialized and dissolved, I realized how much tension and busyness I’d been carrying in my mind and body. I had to work to recall the source of all that vague but profoundly felt concern. Less than one hour. Total relaxation. No pill could work any faster.

In fact, Feinstein’s most recent work focused on the effects of a single hour of Floatation-REST on people with severe depression and anxiety. Those effects were amazing! With almost no negative side effects (a few folks experienced mild itchiness or dry mouth) the article reported participants experienced significant reductions in anxiety, stress, muscle tension, pain, depression, and poor mood. As a matter of fact, “there was … a substantial improvement in mood characterized by increases in serenity, relaxation, happiness, positive affect, overall well-being, energy levels, and feeling refreshed, content and peaceful.”

These positive effects were more pronounced for the group with anxiety and depression than the healthy control group. In other words, the more they needed it, the more it helped.

These positive effects were more pronounced for the group with anxiety and depression than the healthy control group. In other words, the more they needed it, the more it helped.

Previous research showed that the positive takeaways of REST included lowering blood pressure and levels of the stress hormone cortisol. People also experienced increases in well-being, and performance. As if that weren’t enough encouragement to try floating, a 2014 study looked at the effects of floatation REST on a group of professionals participating in a company-sponsored wellness initiative. The results? “Stress, depression, anxiety, and worst pain were significantly decreased whereas optimism and sleep quality significantly increased.”

But how does it work? After all, I’m as Western in my outlook as anyone and I want to know the mechanism. What’s going on in that salty pool? In short, we don’t know yet. Feinstein’s questions focus on the neuroscience of fear, anxiety, and other negative emotions and mood disorders. He believes our bodies play a powerful role in all of our emotional states.

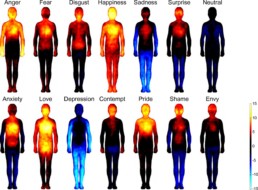

Scientists have learned that our brains are constantly receiving information about how various regions or systems in our bodies are doing, and then engaged in an unconscious cartography of mapping this information. Research in the last decade has shown that people from different cultures tend to locate the physical sensation of particular emotions in the same areas of the body. In other words, our body maps seem to be consistent across cultures and appear to be much more nature than nurture. Feinstein posits that disturbances in those maps might underlie many common mental disorders. If we can tune into our body maps by floating, apparently weightless, in silent darkness, we might be able to heal ourselves.

We have a culture that encourages a habitual tendency to ignore or denigrate the role of our bodies when we aren’t working out, or having sex, or some other explicitly physical activity. And when we do inhabit our bodies we so often do so with critical, editorial judgment rather than curiosity, gratitude, and a sense of exploration. This habit diminishes the quality of our lives, our work, and our contributions to our communities.

And when we do inhabit our bodies we so often do so with critical, editorial judgment rather than curiosity, gratitude, and a sense of exploration. This habit diminishes the quality of our lives, our work, and our contributions to our communities. If we can develop regular practices that allow us to increase our non-judgmental bodily awareness and, in turn, our awareness of the other bodies around us (including the more than human ones) we’ll all be more effective, creative leaders in our work and lives. With practice coming home to the reality that your body and mind are not actually separate, you can live a life more grounded in joy, play, and freedom and feel more like an honest, authentic version of yourself. And those better versions of us can do a much better job of managing ourselves, enhancing the quality of what we offer our various communities and, potentially, the habitats that support all of the above.

After all, one of the premises of Waves to Wisdom is that our bodies are a crucial but undervalued source of creativity, learning, and positive change. We have a culture that encourages a habitual tendency to ignore or denigrate the role of our bodies when we aren’t working out, or having sex, or some other explicitly physical activity.

But the mind-body split is as old as our culture and not easy to overcome. Inside the tank, I felt I’d somehow managed to do just that. Almost instantly, there was a disorienting, enveloping peace that allowed me to just notice random thoughts without chasing them or reacting emotionally. As the hour passed, I experimented with different arm positions and found the most comfortable one: elbows bent, hands above my head, as if surrendering. Life in the tank felt boundless, as if I were in a vast space akin to the beach or a mountainside, without any of the confinement I often feel in my car or even my living room. I was completely relaxed. Utterly supported with none of gravity’s reminders of mid-life joints. I could feel every part of my heartbeat’s rhythm. I lost any inkling of how much time was passing. Once I was surprised by what sounded like someone striking a small bell, a single, loud tone. Then I realized the sound was from a slight movement of my upper lip away from my front tooth. There was a kind of quiet in there I can’t remember ever experiencing and I could hear and feel things that are normally hidden in the din. This is precisely what Feinstein thinks is behind the dramatic results of his recent study of Floatation-REST therapy on people with severe anxiety and depression.

With practice coming home to the reality that your body and mind are not actually separate, you can live a life more grounded in joy, play, and freedom and feel more like an honest, authentic version of yourself. And those better versions of us can do a much better job of managing ourselves, enhancing the quality of what we offer our various communities and, potentially, the habitats that support all of the above.

When the music came on, I couldn’t believe an hour had passed. I climbed out of the tank and felt as though I’d just awoken from the best, longest sleep. After a long, hot shower to wash off the salt and linger in the feeling it left me with, I stopped at the front desk and signed up for regular monthly floats. The TruRest Spa I visited is one of many centers that offer a discount for regular attendance.

So many of us suffer from an inability to stop our habitual frenetic thoughts and motions, to slow down, deeply attend to what’s within, and learn from that attention. It’s no surprise that this is the case. All of our conveniences train us to stay shallow, go fast, and get to what’s next. As difficult as they are to come by in most of our days, periods of deep interiority have the capacity to allow us to sense our most engaged, freest selves. Somewhere in that lost familiarity with calm freedom of just being lie clues to what we might have to offer with different practices, ones that encouraged more depth in our noticing and fuller presence in our receiving. We can emerge from these moments with an understanding of our innate creativity, and how we might use it where we work and live. How we might serve more effectively, more wholly, and in ways that because they are true to who we are deep down in our bodies, energize rather than deplete us.

We can emerge from these moments with an understanding of our innate creativity, and how we might use it where we work and live. How we might serve more effectively, more wholly, and in ways that because they are true to who we are deep down in our bodies, energize rather than deplete us.

In the same interview I quoted above, O’Donohue said

“What amazes me about landscape — landscape recalls you into a mindful mode of stillness, solitude, and silence, where you can truly receive time.”

What I found in the tank was something resonant with the receptivity of an amazed mind as it dances in call and response with vast landscapes. It seems as though sometimes, if you really want to bring about more profound movement and change, to make a beautiful splash in the world, some buoyed stillness is the best place to begin. Even if you only have an hour.

To find a floatation center in your area or learn more about floatation therapy, visit this link: https://floatationlocations.com/

Sources:

“Examining the short-term anxiolytic and antidepressant effect of Floatation-REST” Justin S. Feinstein, Sahib S. Khalsa, Hung-wen Yeh, Colleen Wohlrab, W. Kyle Simmons, Murray B. Stein, Martin P. Paulus. Published: February 2, 2018

“Bodily maps of emotions” Lauri Nummenmaa, Enrico Glerean, Riitta Hari, and Jari K. Hietanen. PNAS January 14, 2014 111 (2) p 646-651.

“Eliciting the relaxation response with the help of flotation-rest (restricted environmental stimulation technique) in patients with stress-related ailments.” Bood, S. Å., Sundequist, U., Kjellgren, A., Norlander, T., Nordström, L., Nordenström, K., & Nordström, G. (2006). International Journal of Stress Management, 13(2), p 154-175.

“Floatation restricted environmental stimulation therapy (REST) as a stress-management tool: A meta-analysis” Dirk van Dierendonck, Jan Te Nijenhuis. p 405-412

“John O’Donohue: The Inner Landscape of Being” On Being with Krista Tippett

“The Acute Effects of Flotation Restricted Environmental Stimulation Technique on Recovery From Maximal Eccentric Exercise” Morgan, Paul M.; Salacinski, Amanda J.; Stults-Kolehmainen, Matthew A. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research: December 2013 – Volume 27 – Issue 12 – p 3467–3474

Interview: Elsa Rivera

To listen to the interview, scroll to the Player at the bottom of the page.

"... my whole neurological being, body, mind, and spirit, is enhanced when I get in the water. And when I come out my perception, my storytelling about any particular "problem" is, it's just redefined.

I don't sweat the small stuff."

~Elsa Rivera

Interview Transcript

Intro

Maia: My name is Maia Dery. This episode impart of a series called the Waves to Wisdom Interviews. The project is a simple one. I seek out people I admire, surfers with what look to me to be ocean centered wisdom practices. I ask them if they’d be willing to share a surf session or two and then, after we’ve ridden some waves together, talk to me about their oceanic habits: about surfing, work, meaning, anything that comes up.

Elsa: Seeing these grown women who can connect with that joy inside themselves even with, when they’re on land, even on the dry sand telling, sharing stories about why that it’s possibly not for them, or it’s too fearful because they have circumstances at home that has have oppressed them, suppressed their joy somehow. They have access to that by getting in.

Maia: Elsa Rivera is a devoted surfer, committed community servant, immigrant, and successful business manager. Our conversation took place overlooking the Pacific on California’s incomparable Central Coast. We’d ridden the chilly waves of a spectacular stretch of shore where graceful arms of kelp and barking, splashing marine mammals can make you feel, for a moment, like you’re a part of a vast ecosystem, a thriving planet abundant with life.

Elsa’s clarity of priority and purpose, and the role her relationship with the ocean plays in that clarity, add delicious nuance to this ongoing story of the power and plain utility of cultivating and stewarding a relationship to the ocean. Welcome to Waves to Wisdom.

Maia: If you are comfortable with it would you tell us your name and age and where you live?

Elsa: Elsa Rivera, I’m 55 years old and I live in Monterey California

Maia: Excellent and did you grow up in Monterey?

Elsa: I’m originally from Columbia. I grew up in Columbia until I was nine and then till 1981 I grew up in Santa Monica.

Maia: This morning we surfed together for the first time

Elsa: We sure did

Maia: We did. We surfed at Asilomar. It’s a place that I have watched people surf before and it’s always been remarkably intimidating to me it seems, well it is very rocky and it also seems prone to wind, and changes… conditions change out there rapidly but it was fun we had a great morning!

Elsa: Definitely! Ah, it’s gorgeous, gorgeous out there.

Maia: And I took off on some waves that scared the heck out of me and that was good.

Elsa: Looked graceful doing it.

Maia: Thank you very much, you’re kind. Let’s see, we were paddling out maybe after a wave or just after having met, changing locations and we both spotted a harbor seal in the top of a wave…

Elsa: My boyfriend…

Maia: Your boyfriend, tell us about your boyfriend.

Elsa: My boyfriend, the same harbor seal, I’m convinced, shows up wherever I surf. I watch him signal to me to move away from rip currents and, kind of, spots to catch good waves.

Maia: That is fantastic! I think I need a boyfriend just like that.

Elsa: You have one actually.

Maia: OK, good! Thank you!

Elsa: He’s out there.

Maia: And we’re, we’re at the beach right now. Can you tell us a little bit about where we are talking to each other?

Elsa: Yeah, this is Del Monte, this is a part of Del Monte Beach and it’s a long, it’s one of the longest stretches of beaches in Monterey.

Maia: And how long have you been surfing?

Elsa: About a year and a half. I’d uh body boarded most of my early teenage life and so I was, I considered myself somewhat of a waterwoman because I never drowned in the ocean.

Maia: You tried and you clearly must of liked it because now you look completely proficient I couldn’t believe it when you said you’d only been surfing for a year and a half.

Elsa: Thanks a lot. For that. Oh yes, absolutely, I loved it from day one and I would just pound my way through whitewater just to get that feeling over and over again and just felt like I could do anything if I could surf.

Maia: I think that many of us feel that way and it seems to be mostly true.

So you have a relationship with the ocean that predates your surfing experience and you were body boarding from childhood, can you talk a little bit more about the role the ocean played in your life as a child?

Elsa: I grew up in Santa Monica, as I said and didn’t know for a long time just because of life, family circumstances that I was so close to the beach and right before junior high I realized that I could just walk to the beach and it was less than three blocks away, long blocks because there were a few hills, and I went to the water for solace. I felt like that was my safe place that could wash away some of the darkness I felt as a very young girl in my family life and at home and in my mind the ocean, being at the beach, and being submerged, even tossed around and tumbled in the in the water was my heart home for me.

(5:41) Maia: So it made you feel better even, even as a youngster [yeah] to get in the ocean?

Elsa: Yeah, I felt embraced and felt enveloped with this almost universal love that my heart was needing and hungry for. And that was my first feel of being embraced.

Maia: Wow, that is a powerful memory and you’ve maintained a relationship clearly and in and continue to enhance and develop your interactions with it and you said to me earlier when we were in the water and again talking just a bit before we began to record that it is a profoundly spiritual relationship for you, from your point of view. Can you talk little bit about your spiritual background and then how the ocean came to play into that?

Elsa: Yes, so I grew up in a very traditional Latin Catholic family and expectation of being, um an awareness of God being a very much Catholic, church-defined, is the best I can say it. But I was drawn to the feminine energy of Mary, the Virgin Mary. I didn’t really think she was a virgin but, so Mary, Mary was just a feminine symbolism in the Catholic Church that I, that I was more drawn to than the male God that was described to me and, over time I went to different churches and at, hidden from my mother, just to try to articulate what I was feeling about believing in a, maybe a greater force or greater spirit of life, without this other definition and I didn’t really find it in churches. But I, I felt at a very young age that I had spiritualism in me rather than Catholic faith and over the years the ocean has become more of the spiritual connection to a life force for me and some of that is defined with my recognition of an ocean deity who I know as Yemanjá and in many Latin and Afro religions. She is the deity of the ocean, she is the mother of life force and so I connect with the idea, the concept of the ocean being a feminine energy, a life source energy, emotional, spiritual, giving. And I, I learn a lot that way.

Maia: How did you learn of this ocean deity and, and, and did it resonate with you immediately?

Elsa: Absolutely immediately. I had come to know about her through, um, the Yemanjá Festival in Santa Cruz and I began to read about her and she became more and more pronounced in my life when I spent 18 months in Brazil. Yemanjá is very much revered in Brazil. There’re rituals, instead of just celebrating New Year’s, the month of January is dedicated to ceremony and rituals in honor of Yemanjá.

And then recently going to Cuba I was part of a casa paticular which is just a place in a person’s home that you rent, where during the week they were doing rituals to, for chosen people who be.. who would become saints in Yoruba religion and they spoke a lot about Yemanjá and her mother Oshun. So in Cuba and in Brazil there are many ocean deities and whoever you resonate with is your deity, like, only you know.

Maia: Interesting, you have a lot of control over who you choose to honor.

Elsa: Yeah, um, well she chooses you, she reminds you that in by way by demonstrating how inspired you are, how motivated you are to learn about her, to know that she’s, she’s your deity.

Maia: Daughter of Earth and Sky, Yemonja is a diety from the Yoruban tradition, which originated in present day Nigeria but took root through the Caribbean as the Atlantic slave trade spread Yorubans far from their homes. Britannica says “Yemonja has been likened to amniotic fluid, because she too protects her children against a predatory world.” Her name is derived from words that roughly translate to “Mother whose children are fishes” and she’s the protector of those on and in the water.

Maia: So since learning about Yemanjá… Now you have this focus, a way to think about, read about, learn about this relationship. Can you talk about maybe the ways that your relationship with the water in your opinion has played out in your life story?

Elsa: I feel that to this very day the ocean has taught me about the, the varying tides of emotions and experiences and the lack of permanency in our lives. To be very present-moment because once you’re in the ocean you, there’s very little you can actually process, think about, the mind chatter stops because your survival sometimes is based on your ability to stay aware of the sites, sounds, smells, ocean currents, what’s happening with other people and that becomes a very present moment existence and again just be happy about, whether you have small waves or big waves, if there’re waves at all, that there is an ocean at all to be the life force, that, that that moment is, the joy of that moment is not defined by the size of the wave but the ability to have the freedom to even be in the water.

Maia: And then getting out of the water in what ways does that practice, in what ways do those experiences manifest, do you think?

Elsa: It’s almost instant application. That– I subscribe to that Blue Mind experience. It says that my whole neurological being, body, mind, and spirit is enhanced and changes when I get in the water and when I come out my perception, my storytelling about any particular, “problem” is, it’s just redefined. I don’t sweat the small stuff. [Laugh] and that, like waves, emotions, especially high peak or low emotions, can just be watched and experienced without any sense of control, leaning into ‘em, like kind of how you lean into a wave to catch it. Just being able to be gentle with yourself and not push any extremes.

Maia: You told me a story. This is a terrifying story, about going surfing at night. [oh, yeah] Could you tell that story?

Elsa: Yes. So I challenged two other mermaids to go to Asilomar, your now favorite break, during a super moon. It was a beautiful, beautiful night. The moon was very, very bright on the beach, it was about 11:30 and we wanted to get in by midnight but the ocean was very, very black and tumultuous lot of seaweed too that day and high tide so I thought it was really smart and following a friend’s advice by making sure we all wore white T-shirts or white shirts so we can see each other in the darkness and I happened to choose one that was really too big for me. It was a men’s size medium or something that I got given to me in Brazil I thought this is good to be a good one I don’t ride, I don’t bike ride so this where I’ll be able to to use it. So we paddled out and we had to really punch through the whitewater quite a bit and the other two women had gone further before my, my board just jumped up against the, the lip of the wave and it tossed me backwards and tossed my shirt over my head and I began to essentially suffocate myself with my shirt and much like what she has taught me in the past, in other experiences about trust and submission, I just really let it, let myself go. I knew I could float to the top. There was something that I knew in that trust, that I could also just let, allow not breathing so hard and suffocating myself with my shirt, that would allow the shirt to float as well and that’s how I got air back in my lungs. I surfaced and tied the T-shirt back up pretty tightly so I could go right back in and not be afraid.

(15:29) Maia: What was it like surfing at night when you couldn’t see the waves?

Elsa: It was terrifying and beautiful, and mystical all at the same time because all your other senses wake up. You’re, you’re feeling the current in a different way. I, I was trying to explain to partners that were there that I could smell the seaweed exposed to air when the wave was forming or curling over us because I couldn’t see it at all and each of us had different experiences about how our senses woke up differently.

Maia: What an amazing memory [yeah] really just calling that up even through your memory I am amazed that you had the courage to go out there and do it and that you discovered these things about the way your senses interacted with the darkness, that sounds profoundly instructive the rest of the time when you can see.

[Exactly] We are missing so much because so visually dominated [yes].

Elsa: I’ve never seen the ocean so black, which was just gorgeous. And I’d do it again.

Maia: And you’d do it again? Then you probably will. [LAUGH] Good, and what, what is your profession, your professional background and has your relationship with the ocean do you think played out in that part of your life at all?

Elsa: Oh, yes. I’ll say that I was inspired as a very young girl to become a nurse practitioner, I wanted to be a midwife actually. And so that propelled me into actually becoming a direct patient care nurse and when I moved to Monterey I got my Associates Degree and continued with patient care and in-home care and decided that this is an avenue of nursing that was very much interesting to me in that it was a holistic approach to taking care of patients at home. So ultimately I ended up transferring my skills to healthcare administration and I ran a local home care agency for about 25 years.

Probably into my 24th year I realized that I had overstepped that caregiver to caretaker, part of myself that couldn’t say “no” when I was on call for a year 24-7, just really overdid it on the whole caring part. And I just reevaluated the fact that I could, I could really give, be of service in different ways and translated some of the stuff that is familiar or similar in all industries and administration and offered to help run a business of my friend’s for 18 months in Brazil with a completely different kind of industry, laser technology. So it was no longer direct patient care, didn’t involve patients, but ultimately resulted in a purposeful time there, helping this person understand the differences in, about the Latin culture and imposing corporate, Americanized ways of doing business in a country that was refusing to accept them.

Maia: Fascinating.

Elsa: And so that’s what I’m still doing, I’m doing business management, I outsource myself when people are short a CEO, an administrator in healthcare, a business manager, and other industries and I limit and I choose wisely and very specifically the type of clients that I, that I have because I feel influenced by what I’ve learned about the ocean and wanting to be in it all the time, that the quality of my life is not about what I do in my work, work is a means to an end just for the survival that’s important to all of us. But my life sustenance, my joy is really about two things, and that’s giving in my community to the service projects and continuing this, ever expanding lifelong relationship with surfing and the ocean.

(20:05) Maia: Another topic that you broached which I find fascinating and I work with young people and most of them, although many of them are going six figures into debt, most of them don’t have any idea about how important money is in their life and you, you talked a little bit about that in the surf session but would you talk a little bit about it, and the relationship with money which you already sort of brushed up against in terms of career but how important healthy relationship with money is to the kind of life you’re describing?

Elsa: Yeah, that’s actually another water symbol for me because I really do believe that that money is currency. I feel like I have a healthy friendship with the concept of money. I’ve made a lot of money in my life and, and I was comfortable with all my little, little creature comforts and stuff but really I define having money as a form of movement and freedom, which is a current, that I can have current in my life. So I worked really hard and very intentionally to remove all debt in my life and it, it allows for me to have a relationship with money where I don’t have a neediness to make money but I can choose to make money for exactly what I need for a plan or for the immediate moment and have more of my freedom than enslavement to the concept of making money.

Maia: And you are the mother of two children [I am] Your son, you tell me, is a big wave surfer?

Elsa: Yes, he is, he started, surfing was his deal so that’s why I didn’t surf for a long time, that was his sport. I was a surf taxi mom for most of his teenage years. He actively competed and he is still mostly just a big wave surfer.

Maia: And you, you clearly are fine with that, and trust him to not hurt himself.

Elsa: Yeah, I do. I was thinking that what I used to joke around with him when he, he went to Mavericks when he was 17 years old but didn’t tell me that he was going until afterwards and I said, “What was that like?” and he said, “Well it’s like falling off the 65 story building and then having it come on top of you afterwards.” So I sent him, “Ever think of taking up, you know, an indoor sport like chess?” but I never meant that I never meant it.

He was a boogie border and I went to Asilomar one day he was boogie boarding and I just got inspired and we have this thing now in life that whenever there’s something that we need to have a rite of passage about very close we’ll just say, “It’s time.” and so I went to Sunshine surf store over here and bought a board, I didn’t know what I was buying and I showed up at Asilomar, he’d been boogie boarding in the I was a standing on the beach with the surfboard and he said, “What, what are you doing, Mom? What’s that? And I just said, “It’s time.” and I gave him a surfboard [Wow] so I figure he said he said it best, he said people say, “Aren’t you afraid of sharks or getting hurt out in those big waves?” And he said, “Have you seem what’s on the street lately?” Even at a really young age he knew that the ocean was his safety spot too.

Maia: So smart! [Yes] and clearly you both share that love of the excitement and the ocean, all that it has to offer. OK, is there anything else about your relationship with the ocean or the way that surfing or being near or in or on the ocean has impacted your life that you’d like to share?

Elsa: I think it just goes directly to my experience teaching young girls to surf and through that vehicle empowering their, conquering fears and having a stronger self-esteem. Where I’m drawn to expand that, and I feel that I’ve been really successful at it and not successful like in the competition, competitive way but more like watching the same effects with older women or grown women, is taking women into, into the water for the first time. One story I’ll share is that one of the moms had been on the beach for a while. They came all the way from Greenfield and all the way I’m talking less than 45 minutes away but they’d never been to the beach, they’d never seen the water, and she kept talking about, “One day I’m going to try that. I’ve only been in the water up to my knees in the swimming pool.” and I, I didn’t even focus on , “Hay, I’ll teach you how to surf, or any conquer, help you conquer the fear of water, I just said, “Ever put on wetsuit?” She said. “No.” and, um, “I said, “That’s half the battle right there, want to try it?” So, then she was in a wetsuit and she talked about, while she was putting her wetsuit on she talked about her body being too big, she really needed to work out more, she was out of shape, all these body image things that are pronounced in women everywhere that we’re trying to change, in a wetsuit especially, that’s one of the reasons I love surfing in this area because we all look like seals and there’s, there’s not an immediate, competitive body image thing going on. So, so I tell her,

“Well, I’m a professional round person and I love my body and I like looking like a seal and, and seals like the water so we can just go try it.”

And so she was really tentative but I said you’ve already gone as far as your knees, you want to try that?” We started there. I said, “You know, one of my favorite things when I was a little kid is jumping waves, want to to jump waves?”

“Oh, okay maybe, I don’t know.”

So we started to jump waves. And the same delight in this 48-year-old woman’s face that we see in the six-year-old faces began to take over her and then she wanted to jump more waves. And then we thought maybe we could jump a wave and then go under a wave.

And it was just this progressive thing but really it was allowing someone to be in their kid again to play in the water and then she wanted to get down to business. “What about his board thing?” And before we knew it we spent quite a bit of time just having her now jump waves on the board and feel just that floatation and she just kept saying,

“This feels so good. I’ve never felt anything like this, I feel free!”

And that just continued throughout her whole experience and when she got out of the water, um, she said, “What can I do to practice my pop-up?” and I told her draw a surfboard on her on the floor with tape and all her kids and her can do pop-ups and all this other stuff. This woman just had so much joy that resonated through the entire time she was on the beach and every time I see her that same look in her face and she thanks me and it’s not even about that but she just comes to me with this feeling of like, “ I remember that joyful moment” whether she does it again or has the opportunity because of whatever obstacle she had before to continue, she’ll always have that experience that, that will relive itself and that’s very powerful.

Maia: Joy in and of itself is so powerful. It’s fleeting in its way but just to know that you have the capacity for that. [Yeah] especially as an adult [Yes] you may have had life circumstances that for one reason or another have separated you from that feeling [yes]. It really is a powerful force and it can do profound work in the world, when you get in touch with that.

Elsa: I believe that! I believe that. Seeing these grown women who can connect with that joy inside themselves even with, when they’re on land, even on the dry sand telling, sharing stories about why that it’s possibly not for them, or it’s too fearful because they have circumstances at home that has have oppressed them, suppressed their joy somehow. They have access to that by getting in.

Maia: After Elsa and I had this conversation her relationship with the ocean and desire to include others in its benefits lead her to an organization called GI Josie.

GI Josie’s mission is to provide single women veterans with an environment and opportunities that eradicate the suffering and suicides arising from the Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and Military Sexual Trauma that these vets often suffer with as a result of their service in the U.S. Military.

Elsa is profoundly influenced by the work of J. Wallace Nichols, a marine biologist whose most influential work popularizes research showing the mental and physical health benefits of being on, near, or under water.

Elsa launched GI Josie’s Bluewater project which gets these women on the water, sometimes to learn to surf, sometimes just playing in the waves or learning about the ecology in a local wetland. Many of these women Elsa is able to serve in the program face significant challenges. One veteran who had been bound then sexually assaulted was upset by the similar feeling of the tight wetsuit on her wrist. Ultimately she rolled up her sleeves and got in the water. Hers is just one of many similar stories of service-related trauma, too many of which don’t have happy endings.

To help the women overcome their initial fear, Elsa tells them about Yemanjá and asks her to protect each of them by name. GI Josie is actively fundraising to build a residential ranch to allow these women and their children to transition back to healthy, productive civilian lives. I’ll post information on the website so you can learn more and, if you’re able, make a donation.

Maia: Okay, so you also related to me earlier this, this just intriguing and artful interpretation, tell me that the ocean deity’s name again [Yemanjá] this interpretation of what is Yemanjá’s storied vanity.

Elsa: So Yemanjá of all the deities is considered a very vain deity and I dance Samba, so there are several songs dedicated to Yemanjá and uh we use mirrors and use our hands very much like hula to tell the story of her adorning herself at all times and wanting to be adored and wanting adornments and in the world and in religion people have taken that to an extreme by getting actual offerings to Yemanjá in different parts of the world. In Cuba, people offer animals, slaughtered animals, and toss them in the ocean as as an offering to Yemanjá. In Brazil people build small boats and they put jewelry and coins, and food and lipstick and all these things, which break my heart in a way because they’ve taken a materialistic approach to the concept of her vanity. But in my widening and aware need for, to be a part of conservation of the ocean and beaches, I see that as just a very, very simple, powerful request from her to keep her beautiful. To let, let those things that already naturally adorn her, the animals, the kelp, the shells, those things that belong to her, preserve them so that she can just continue to be beautiful.

Maia: One of the reasons that struck me is that it sometimes seems to me in my optimistic moments that we are in the process of and I work with young people and it feels like we’re the process of turning some kind of a corner in which maybe out of necessity because they know that their material lives are not going to be what their parents’ and grandparents’ were, that young people are turning towards experiences as markers of success and a life well lived in a way that causes them to turn away from material possessions but that, that kind of value and it’s, it’s absolutely understandable why in a world where struggling for material well-being at the most fundamental levels, you would give, give up things which were so hard won on to the deity that was most meaningful to you and it, I can’t wait for other people to hear your interpretation because it’s not just the interpretation itself that is powerful but your willingness to, to understand, to see what this story has to offer you not in the way of dogma but as a way of connecting with the needs that are all around you as you move through this, with this world.

Elsa: Yes, yes, she’s not really wanting for people to give her more stuff but to see their own duty in approaching her, preserving her so that they themselves can get her life force in her and her life sustenance in return, so less is more. She already has everything she needs.

Maia: Yemanjá has every thing she needs but clearly our oceans are in trouble. Elsa’s story and her work with GI Josie is not rare but could be much more common. Many of us know from our own experience the healing power of water. The Blue Mind concept I mentioned earlier, along with the book that bears the same name is a great place to start if you’d like to learn more about research explaining the effects of water on our brain. In the coming weeks, I’ll post about some of the research that tells the story of what happens our water-loving experiences through a scientific lens and the work that’s underway to show that surf therapy can be more effective than other forms of treatment.

If you’re enjoying these interviews, we’d be most grateful if you’d post a review on iTunes. Our next retreat is scheduled for March of 2019. If you’re interested in learning more or if you know of someone who works with a business who might be interested in sponsoring this podcast and reaching our growing audience, please drop us a line at info@wavestowisdom.com.