On good afternoons, here at the blue metal patio table where I work, I lean back and close my eyes in search of some elusive word or idea and I can still see lines of swell coming towards me. To have this sort of oceanic wave overlaying one’s usual electromagnetic brainwave is a good influence. On days like today, when I’m practicing this discipline well, the refrigerator’s hum and the call of the Carolina wren nesting under the bedroom window are part of the same whole as the white noise of the rough surf punctuated by the scoop of resting skimmers. Skimmers must get tired their from long, low flights just above the water’s edge, open beaks dragging along the surface. Holding tea on my palate for a few extra seconds, I wonder what that kind of ocean practice must look like through their eyes and feel like in their beaks.

Over years of regular play, effort, and immersion, the ocean has given me new ears to hear and I’ve gradually become a better listener. It isn’t just the waves themselves or the liquid logic of other surfers I feel attuned to. The waves’ chaotic beauty and my own fear, innumerable failures and rare moments of accomplishment seem to have allowed me to feel more connected to just about anyone honestly grappling with big, powerful, overwhelming questions and forces. These days, that’s a lot of us.

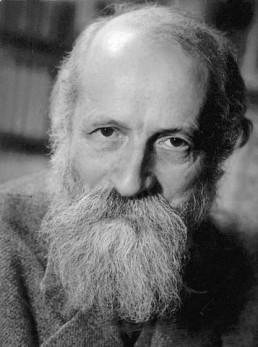

Learning to surf is, as Ethan Crouch observed in the latest Waves to Wisdom Interview, “an ongoing practice.” For me, part of that practice involves being open to taking off on some unexpected, even uncomfortable rides, especially off the board. The latest was a difficult but immensely rewarding few days submerged in the writing of Martin Buber. Ethan inadvertently assigned the reading, in particular Buber’s book I and Thou (Ich und Du), when he cited it as one of his primary philosophical influences.

Buber was a Jewish theologian and philosopher who wrote the first version of I and Thou between the two world wars. I’m neither Jewish, theological, or even theistic but it’s precisely the creative potential of this sort of dis-orientation that lies at the heart of Waves to Wisdom. Our reactions to the unfamiliar and unexpected have equally unfamiliar and unexpected lessons to offer. I’m grateful to Buber for the intellectual and existential workout, and for the deepened appreciation for the time with Ethan.

In his introduction of Ich und Du (I and Thou), translator Walter Kaufmann warns that the original work, with its plays on words and unconventional use of language, is essentially untranslatable. Since my German doesn’t extend far past “bratwurst,” I’ll just have to trust him.

One of Kaufmann’s first tasks is to take issue with previous translations’ use of “Thou” for “Du.” Thou, Kaufmann, notes, is just plain stuffy. It’s true— when’s the last time you “thou’d” a loved one? As I understood him, one of Buber’s goals is to make a case for seeing with open eyes and hearing with new ears. He’s making a case for the importance and reward of spending all our days swimming in the waters of deep love and presence, a love that is all around us in the workaday world.

“Thou,” Kaufmann notes, “immediately brings to mind… God of the pulpits,” a power sequestered in the sacred sabbath. Instead, Kaufmann translates “Du” as “You”— the You of lovers, parents, true friends, and those who “pray spontaneously” to an intimate diety. Reading in the wake of working on the Ethan interview, this work is an evocative manual for accessing connection in a world that creates and pushes us into separation and fragmentation. Sow how do you do it?

Buber’s cornerstone idea is that we humans build our communication and, in the process, ourselves with the use of two “basic words”— I-It and I-You. We are always choosing between one or the other in all of our interactions with other people and the world. We speak these two basic words with our hearts, attitudes, actions and values and “by being spoken they establish a mode of existence.” Every time you use the word “I,” in thought, speech, or deed, you choose I-It or I-You and, in the process, alter the form of your self.

When we speak I-You we are intimate, open, and utterly present. We feel the You we encounter and ourselves as part of the whole, infinite, eternal You. Speaking I-It puts us in a place of distance, categorization, abstraction or analysis and we might see the other before us as just one of many, an object to be used or experienced.

Now, Buber doesn’t come right out and say I-It is terrible but the whole work is a lavish literary celebration of the benefits of speaking I-You as much as possible. Buber thinks no human is free from necessarily existing in both modes. Our lives are a combination and so are we.

The connection to Ethan’s life story was clear to me. I found his sense of what Brené Brown calls “true belonging” inspiring. In my work as a teacher, mentor, and coach and also in the messy beauty of my own life, I’ve worked to guide many people wrestling with how they could find or cultivate this sort of connection.

Buber runs right at the pervasive problem of loneliness and isolation in I and Thou and, as he’s a theologian, it’s no surprise that his suggestions are all embedded in a relationship to all that’s divine. He has thoughts about overcoming loneliness but this is no feel-good, self help prescription that could be bulleted into 10 takeaways that will make you rich and happy.

Feelings, in fact, are only a part of what he thinks is required for connection and community to thrive. He writes, “Loving community is supposed to come into being when people come together, prompted by free, exuberant feeling, and want to live together” but “that is not the case.” All members of a true community “have to stand in a living, reciprocal relationship to a single, living center.” For Buber, the word he uses to describe this center is sometimes the You-world and sometimes God. If my reading is accurate, we are both and both are us.

According to Buber, “The You-world coheres in the center in which the extended lines of relationships intersect: in the eternal You.” (p.148) In our interview, Ethan told the story of the extended lines of his own relationships with fellow activists. After working long, hard hours together to effect change or pass legislation on the ocean’s behalf, with no guarantees of success, Ethan realized what he felt for his companions was unadulterated love. There is I-You all over this tale.

These activists share love for and a desire to protect the ocean from further assault from those in the It-world who only use and measure it. It certainly looks as if the ocean might be functioning as the single, active center of the community. It is, after all, the biggest active center in our earthly corner of the cosmos. And, in Buber’s language, speaking You to it can be profoundly transformative.

But life can’t all be I-You. Most of us do work that consists of analysis, abstraction, measurement or categorization. We inevitably return to our desks, screens, and boxes. Certainly, as a construction consultant with a “passion for scheduling” (!!!), Ethan spends much of his time It-ing all over the world and that’s a good thing! Buildings need to be thought about, analyzed, categorized, and measured. But maybe his capacity to carry that active, oceanic center into his work world alters him and his relationship to his work for the better.

According to Buber, “Every actual relationship in the world alternates between actuality and latency… You must disappear into the chrysalis of the It in order to grow wings again.” But if the relationship is pure, “latency is merely drawing a deep breath during which the You remains present.” (148)

When Ethan talked in our interview about developing long term relationships with his clients, building public projects, and protecting his home stretch of coastline it certainly sounded as though the latent You of his regular, loving immersion in the ocean, in his words, “that experience with the Thou,” might form the breathing center of the his work life in the It-world.

As a theologian, Buber’s work is to understand, articulate, and study the nature of the divine. While the language of God (and especially the Fatherly sort) still gets my back up at times, a stance of reverence before the continual revelation of a relationship with a higher power gets more comfortable every time I get in the ocean with an intention to surf. I will not be in charge of what that looks like. Not ever. Each wave is more practice in understanding that predictions are rarely true, and even current happenings are bursting with implications we can neither fully perceive nor accurately assess. Analysis in the moment interferes with full presence and is sometimes worse than useless.

To surf as a wisdom practice, the ocean can’t be an It. To borrow Buber’s language, if we “observe it” instead of “heeding it” and “instead of receiving it, [utilize] it” then we’ve missed the most substantial, life-giving gifts it has to offer.

The ocean gave and gives us life on this planet. Gratitude before the giver seems not only polite but prudent. I’m intimately connected to it in my quotidian everyday, and it infuses me with a sense of connection, of belonging. The ocean is water with life in it and so am I. There it is easier for me to feel part of a whole, a You among the You. And its vast horizons and geological age are plenty close enough to eternal for my tiny mind. Especially when, fingers cramping and pen in hand, I lean back to stretch, close my eyes and see waves undulating towards me.